It is one of the world’s oldest systems of verifiable jurisprudence next to the Vedic laws. And these native Irish laws bear striking resemblance to the laws of other pre-colonial or non-colonial societies. Much of the Brehon Laws were codified into books at a later date under the direction of Saint Patrick and King Laegaire. This law was of the people, it was alive, fluid, electric and it was loved.

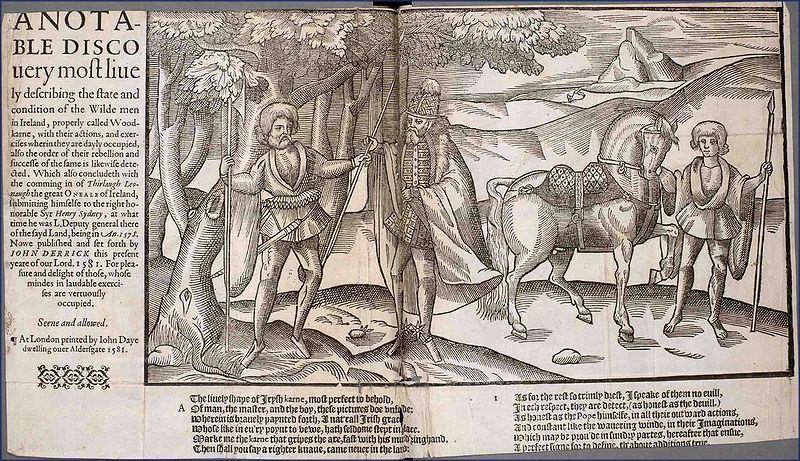

The laws of a land govern the nature of that land, so in order for the conquest of Ireland to be successful, it was believed to be essential to eradicate the Brehon Laws and replace them with the Courts and Laws of the Crown so as to bring the land under the Kings’ dominion. This attack on the law spanned many years, but remnants of the Brehon Law existed up and until the 17th C. when it was finally stamped out, aided heavily by the oppressive penal laws.

The Irish old and natural love for the Law was replaced by fear and distrust that remains to this day. The Nation re-gained her right to govern and make her own laws after generations of struggle, but alas we see that the original system of law was never restored; that grievance was never addressed. This shows however that the system of law in place today is relatively young compared to the system that preceded it and in the short three hundred years or so we can directly see the impact this imposed system has had on us. The modern view of the ‘legal system’ can be seen as a reaction and direct consequence of unjust systems of punishment and penalty. It seems as though justice is dead, but, it is just dormant, laying patiently, waiting to be rekindled.

The preamble of the earlier Statutes of Kilkenny makes no excuses in outlining the importance for the English in eradicating the Irish system of jurisprudence.

It states that the English settlers had for a long time been governed and ruled according to English common law; “but now many English of the said land, forsaking the English language, manners, mode of riding, laws and usages, live and govern themselves according to the manners, fashion, and language of the Irish enemies”.

This shows that even the English settlers, sent here to establish a new form of governance, found themselves naturally drawn to the customs and laws of the native Irish people. Settlers would revert to the Brehon system for justice and in doing so denied their allegiance to, and the ‘protection’ of the Law offered by the Crown.

Item IV states that:

“…whereas diversity of government and different laws in the same land cause difference in allegiance, and disputes among the people; it is agreed and established, that no Englishman having disputes with any other Englishman, shall henceforth make caption, or take pledge, distress or vengeance against any other, whereby the people may be troubled, but that they shall sue each other at the common law; and that no Englishman be governed in the termination of their disputes by March law nor Brehon law, which reasonably ought not to, be called law, being a bad custom; but they shall be governed, as right is, by the common law of the land, as liege subjects of our lord the king; and if any do to the contrary, and thereof be attainted, he shall be taken and imprisoned and adjudged as a traitor and that no difference of allegiance shall henceforth be made between the english born in born in Ireland, and the English born in England, by calling them English hobbe, or Irish dog, but that all be called by one, name, the English lieges of our Lord the king; and he who shall be found doing to the contrary, shall be punished by imprisonment for a year, and afterwards fined, at the king’s pleasure; and by this ordinance it is not the intention of our Lord the king but that it shall be lawful for any one that he may take distress for service and rents due to them, and for damage feasant as the common law requires.”

The fears of the foreign rulers were realised later during the great Gaelic revival which saw many of the settled Norman families turning away from their own customs and adopting the Irish customs wholeheartedly. A situation which gave rise to the phrase: Níos Gaelaí ná na Gaeil féin, meaning “more Irish than the Irish themselves”.

The question on the prudent historian’s lips should be, why? Why was it that these landed nobles would eventually, and voluntarily, choose to adopt the Irish laws and customs over that of their own? What is it about these laws that were so appealing and attractive that they were willing to turn their backs on their own roots and customs?

The Brehon Academy is working to explain that and find some answers.

Sources:

– P.W. Joyce, A Smaller Social History of Ancient Ireland, 1906, Chapter IV, ‘1. The Brehons’.

– A Statute of the Fortieth Year of King Edward III., enacted in a parliament held in Kilkenny, A.D. 1367, before Lionel Duke of Clarence, Lord Lieutenant of Ireland. http://www.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~irlkik/statutes.htm