At the start of October, I had the dual pleasure of making my first trip to Iceland, where I also got to hear eminent scholar David Friedman’s analysis of ancient Icelandic Feud Law during European Students For Liberty Iceland’s Annual Conference.

Notable parallels and interesting differences can be drawn between this and the ancient Irish Brehon law, particularly with reference to the eneclann (honour price), and eric fine (the penalty for causing loss of life).

Friedman is of the opinion that the Icelandic system offers more valuable insights because he feels the Irish source material is not reliable and inconsistent.

We amicably disagreed on this point, I explained how we had many references of suitable antiquity, and the discrepancies could mostly be explained through a more in-depth understanding of the Brehon law’s intricacies. Still, the fact that I had the opportunity to discuss, and even disagree, with David Friedman was a rare treat.

I’m including a particularly insightful extract from David Friedman’s site about the History and Institutions of Icelandic law for readers of the Brehon Law Academy to make their own comparisons.

In the latter half of the ninth century, King Harald Fairhair unified Norway under his rule. A substantial part of the population left;[21] many went either directly to Iceland, which had been discovered a few years before, or indirectly via Norse colonies in England, Ireland, Orkney, the Hebrides, and the Shetland Islands. The political system which they developed there was based on Norwegian (or possibly Danish[22]) traditions but with one important innovation–the King was replaced by an assembly of local chieftains. As in Norway (before Harald) there was nothing corresponding to a strictly feudal bond. The relationship between the Icelandic godi and his thingmen (thingmenn) was contractual, as in early feudal relationships, but it was not territorial; the godi had no claim to the thingman’s land and the thingman was free to transfer his allegiance.

At the base of the system stood the godi (pl. godar) and the godord (pl. godord). A godi was a local chief who built a (pagan) temple and served as its priest; the godord was the congregation. The godi received temple dues and provided in exchange both religious and political services.

Under the system of laws established in A.D. 930 and modified somewhat thereafter, these local leaders were combined into a national system. Iceland was divided into four quarters, and each quarter into nine godord.[23] Within each quarter the godord were clustered in groups of three called things. Only the godar owning these godord had any special status within the legal system, although it seems that others might continue to call themselves godi . (in the sense of priest) and have a godord (in the sense of congregation); to avoid confusion, I will hereafter use the terms “godi” and “godord” only to refer to those having a special status under the legal system.

The one permanent official of this system was the logsogumadr or law- speaker; he was elected every three years by the inhabitants of one quarter (which quarter it was being chosen by lot). His job was to memorize the laws, to recite them through once during his term in office, to provide advice on difficult legal points, and to preside over the lögrétta, the “legislature.”

The members of the lögrétta were the godar, plus one additional man from each thing, plus for each of these two advisors. Decisions in the lögrétta were made, at least after the reforms attributed to Njal, by majority vote, subject apparently to attempts to first achieve unanimity.[24]

The laws passed by the lögrétta were applied by a system of courts, also resting on the godar. At the lowest level were private courts, the members being chosen after the conflict arose, half by the plaintiff and half by the defendant–essentially a system of arbitration. Above this was the thing court or “Varthing”, the judges[25] in which were chosen twelve each by the godar of the thing, making thirty -six in all. Next came the quarter-thing for disputes between members of different things within the same quarter; these seem to have been little used and not much is known about them.[26] Above them were the four quarter courts of the Althing (althingi) or national assembly–an annual meeting of all the godar each bringing with him at least one-ninth of his thingmen. Above them, after Njal’s reforms, was the fifth court. Cases undecided at any level of the court system went to the next level; at every level (except the private courts) the judges were appointed by the godar, each quarter court and the fifth court having judges appointed by the godar from all over Iceland.[27] The fifth court reached its decision by majority vote; the other courts seem to have required that there be at most six (out of thirty-six) dissenting votes in order for a verdict to be given.[28]

The godord itself was in effect two different things. It was a group of men–the particular men who had agreed to follow that godi, to be members of that godord. Any man could be challenged to name his godord and was required to do so, but he was free to choose any godi within his quarter and to change to a different godord at will.[29] It was also a bundle of rights–the right to sit in the lögrétta, appoint judges for certain courts, etc. The godord in this second sense was marketable property. It could be given away, sold, held by a partnership, inherited, or whatever.[30] Thus seats in the law- making body were quite literally for sale.

I have described the legislative and judicial branches of “government” but have omitted the executive. So did the Icelanders. The function of the courts was to deliver verdicts on cases brought to them. That done, the court was finished. If the verdict went against the defendant, it was up to him to pay the assigned punishment–almost always a fine. If he did not, the plaintiff could go to court again and have the defendant declared an outlaw. The killer of an outlaw could not himself be prosecuted for the act; in addition, anyone who gave shelter to an outlaw could be prosecuted for doing so.

Prosecution was up to the victim (or his survivors). If they and the offender agreed on a settlement, the matter was settled.[31] Many cases were settled by arbitration, including the two most serious conflicts that arose prior to the final period of breakdown in the thirteenth century. If the case went to a court, the judgment, in case of conviction, would be a fine to be paid by the defendant to the plaintiff.

In modern law the distinction between civil and criminal law depends on whether prosecution is private or public; in this sense all Icelandic law was civil. But another distinction is that civil remedies usually involve a transfer (of money, goods, or services) from the defendant to the plaintiff, whereas criminal remedies often involve some sort of “punishment.” In this sense the distinction existed in Icelandic law, but its basis was different.

Killing was made up for by a fine. For murder a man could be outlawed, even if he was willing to pay a fine instead. In our system, the difference between murder and killing (manslaughter) depends on intent; for the Icelanders it depended on something more easily judged. After killing a man, one was obliged to announce the fact immediately; as one law code puts it: “The slayer shall not ride past any three houses, on the day he committed the deed, without avowing the deed, unless the kinsmen of the slain man, or enemies of the slayer lived there, who would put his life in danger.”[32] A man who tried to hide the body, or otherwise conceal his responsibility, was guilty of murder.[33]

Read the full article with references here.

Iceland: The First Parliament

David Friedman spoke about a site of crucial significance to Icelandic heritage called Þingvellir, or Thingvellir in English, as it is said to be the seat of the first parliament when the Althing, or National Parliament of Iceland, was founded in 930 AD.

This was also the site of Lögberg, the Law Rock, a central feature of Þingvellir and focal point of the Althing, from where disputes were adjudged, laws pronounced, and allegiances were reaffirmed.

During my trip I also had the chance to visit this site and it is truly stunning. Breathtaking views of dominant hills in the distance cradling a huge silent lake which lead the mind to wonder about great legends and myths which might have taken place in settings just like this.

Or how, in times long past, one could have stood on this spot in anticipation of the arrival of tribes of Icelanders as they made their procession across those same hills to the annual assembly of the Althing at Lögberg.

From the Grágás lawcode

IT IS PRESCRIBED THAT IF MEN MEET as they travel and one man makes what the law decrees an assault on another, the penalty is lesser outlawry. There are five assaults deemed such by law: if a man cuts at a man or thrusts at him, or shoots or throws at him or strikes at him. And it counts as an assault if a man swings a weapon and a panel gives a verdict that he meant the stroke to land, and he was moreover at such close range that for the matter it could have landed if it had not been stopped on its way, or that he could have reached him.

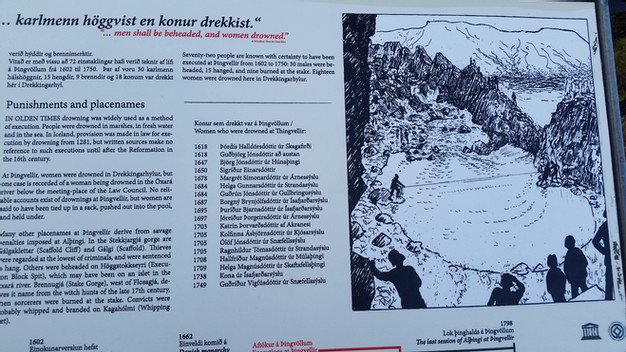

Right-click to view/open images in a new tab and zoom in to read the text.

The Irish had similar sites of assembly with their sacred stones or bíle, sacred trees special to a certain tribe or family and under which important ceremonies of the inauguration, law-pronouncement, marriage, resolution, and contract were performed.

Many of the ruling families had their inauguration rocks and coronation stone upon which generations of their kin had been announced chieftain according to customs in place since time immemorial. Some of these even have footprints embedded in them, believed to be the marks of the race’s progenitor.

Like with Lögberg in Iceland, these were sites for assembly, a gathering of the people to one place to share in a common history and identity. Introduce a touch of poetic Irish romanticism and we learn that these ancient stones and old trees were seen to be silent witnesses and guardians over the tuath’s affairs.

It is no wonder that these and similar sacred sites would be a target for destruction throughout the Anglo conquests, they were evidence of a culture and signified an authority of kingship much more ancient than their own.

And no discussion about sacred political stones would be complete without at least passing mention to the legendary Lia Fáil, or Stone of Destiny.

That magical singing stone which was said to have been brought to Irish shores by the Tuatha De Dannan themselves and which let out a mystical wail whenever a rightful king stood upon it.

Traditionally it sat upon the Cnoc Temhair, the Hill of Tara, in County Meath, the political centre of Ireland and the site of the national assembly for millennia before the coming of the Anglo-Normans.

Check out our video on Royal Inauguration Rituals from our online course Early Irish Culture and Society.