“In early times [in Ireland] wealth is not spoken of in terms of money, which was not in circulation, nor of ownership of land, but primarily in terms of livestock and chiefly of cows.”

-From Cattle in Ancient Ireland, by A.T. Lucas (1989), p 223.

Absence of Coinage Until AD 1000:

Ireland lacked a minted coinage system until approximately AD 1000, when Sihtric III, a Norse king of Dublin, introduced silver pennies modelled on those of Aethelred II of England (O’Sullivan 1949, p. 191). This marked the first native coin production, driven by external influence rather than internal economic evolution. The late adoption of coinage underscores the self-sufficiency of Ireland’s cattle-based economy, which met the needs of trade, legal fines, and social transactions without requiring standardised metal currency.

Cattle as the Primary Currency:

Even after the Anglo-Norman invasion of 1169, which introduced more centralised feudal structures and coin-based economies in some areas, cattle remained the dominant currency in Gaelic Ireland. This persistence reflects both cultural preference and the practical utility of cattle in a predominantly agrarian society. Cattle were not just a medium of exchange but a measure of wealth, status, and sustenance, deeply embedded in social and legal frameworks.

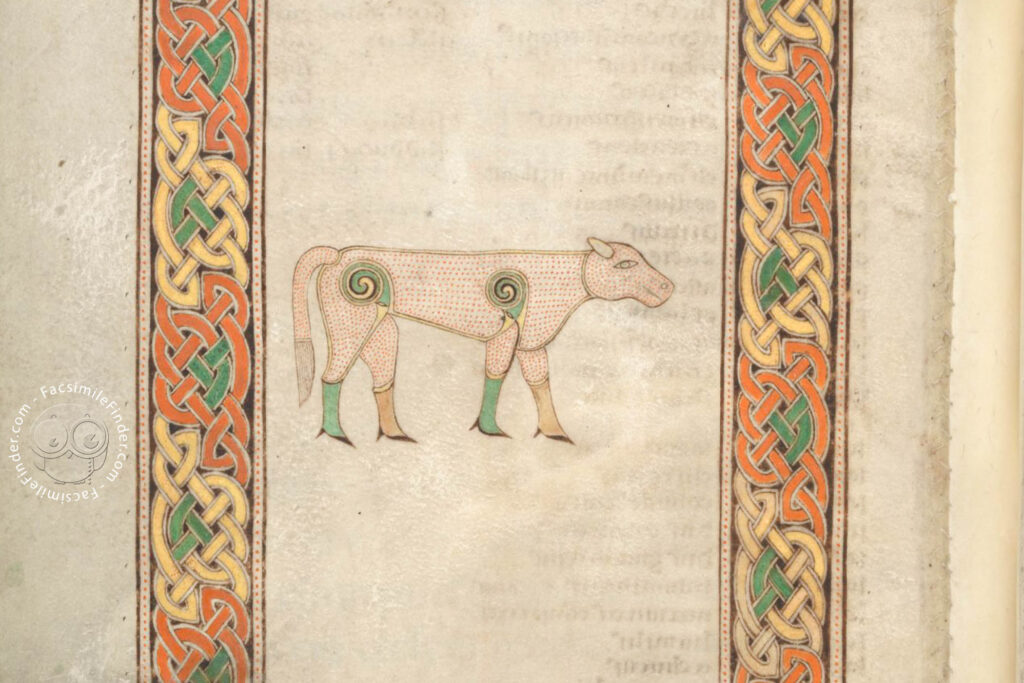

Facsimile of The Calf Symbol of Saint Luke the Evangelist, from folio 124v of the Book of Durrow, 7th C.

Legal Treatise by Giolla na Naomh Mac Aodhagáin (c. 1300):

The Legal Treatise, authored by the chief judge of Connacht, demonstrates the continued centrality of cattle in the legal system.

Fines and payments were predominantly expressed in cattle, indicating their role as a standardised unit of value. A striking example is the fine for the secret murder of a king’s son, set at 210 cows (Binchy 1978, pp. ii, 691.4–691.7).

This substantial penalty highlights the economic and symbolic weight of cattle, as 210 cows represented significant wealth, equivalent to 70 cumals (female slaves) or 210 ounces of silver, based on the valuation system described below.

Main Period of Law-Texts (7th–8th Centuries):

During this period, the milch cow (bó mlicht) with calf was the foundational unit of currency. Its value was standardised against other assets:

- One ounce of silver:

A direct equivalence that linked livestock to precious metal, facilitating trade with regions using silver-based systems. - One-third the value of a cumal:

A cumal, typically a female slave, was a high-value unit, indicating that three milch cows (or three ounces of silver) equalled the worth of one enslaved woman (Kelly 1988, pp. 112–116).

The milch cow’s prominence reflects its productive capacity—milk, calves, and potential for herd growth—making it an ideal unit for an economy centred on pastoralism.

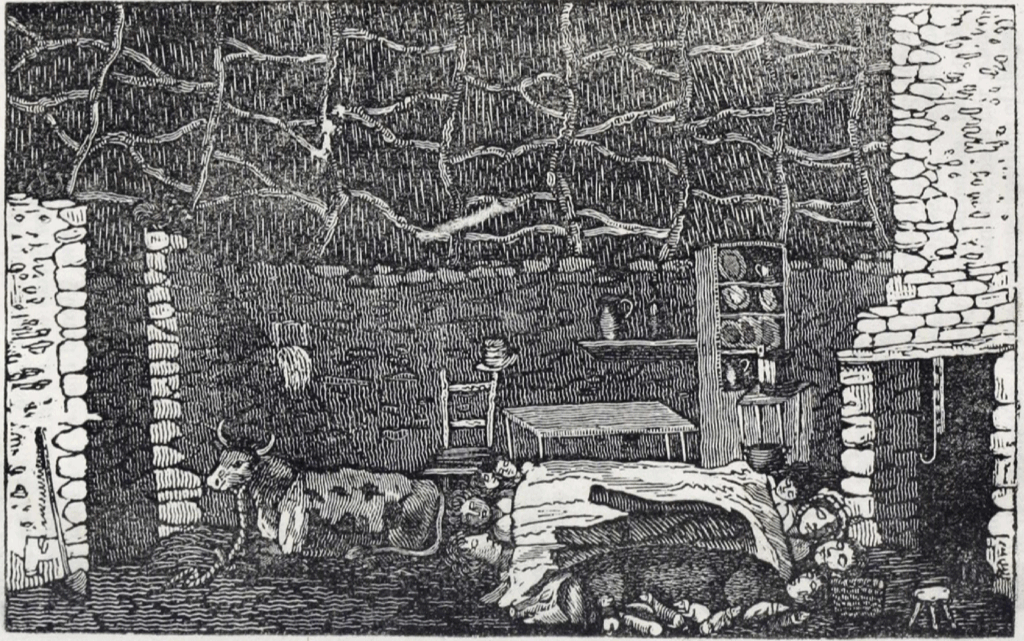

Livestock also served the function of heating a room in a cottage.

Here we see a cow and a sow, and piglets sharing the living quarters (kitchen) of a family (from Connery 1837).

Valuation of Younger Cattle:

The law-texts provide a detailed hierarchy of cattle valuations based on age, sex, and reproductive status, illustrating a sophisticated system for smaller transactions:

- Samaisc (three-year-old dry heifer): Valued at ½ the worth of a milch cow.

A dry heifer, not yet lactating, was less productive but still valuable due to its potential for future calving. - Colpthach (two-year-old heifer): Valued at ⅓ the worth of a milch cow.

At two years, this heifer was further from reproductive maturity, reducing its economic utility. - Dairt (yearling heifer): Valued at ¼ the worth of a milch cow.

As a yearling, its value was lower due to its youth and lack of immediate productivity. - Dartaid (yearling bullock): Valued at ⅛ the worth of a milch cow.

A young male, less valuable for breeding or milk production, was assigned the lowest value among cattle.

This tiered system allowed for precise economic calculations, enabling fines and payments to be calibrated to the offence or obligation without requiring coinage.

Lesser Values:

For transactions involving smaller amounts, values were expressed in terms of sheep, fleeces, or sacks of grain. These served as “small change” in the absence of low-denomination coins, further demonstrating the flexibility of Ireland’s non-monetary economy.

Cattle as a Dynamic Economic and Cultural Institution

The cattle-based currency system of medieval Ireland was not merely a pragmatic response to the absence of coinage but a sophisticated economic and cultural institution that reflected the values and realities of Gaelic society.

Here’s a deeper exploration of its significance:

Economic Sophistication:

- The tiered valuation of cattle, particularly the precise distinctions between a milch cow, samaisc, colpthach, dairt, and dartaid, reveals a nuanced understanding of livestock’s economic potential. The milch cow, as the pinnacle of value, was prized for its immediate productivity (milk and calves), while younger cattle were valued based on their future potential. This system mirrors modern actuarial models, where value is tied to expected output over time.

- The equivalence of a milch cow to one ounce of silver or one-third of a cumal shows an ability to integrate with broader economic systems, facilitating trade with neighbouring regions while maintaining a distinct local currency. This adaptability challenges the notion of pre-coinage economies as simplistic or isolated.

Cultural Resistance and Identity:

- The continued reliance on cattle post-1169, despite Anglo-Norman efforts to introduce coin-based systems, suggests a deliberate cultural choice. Cattle were not just economic assets but symbols of Gaelic identity, tied to the pastoral traditions that defined social status and power. Kings and nobles measured their wealth in herds, and legal fines in cattle reinforced communal values over external impositions.

- The fine of 210 cows for a king’s son’s murder is particularly telling. Beyond its economic magnitude, it underscores the sacredness of life and hierarchy in Gaelic society. The sheer number of cows—potentially a herd that could sustain a community—emphasises the gravity of the crime and the restorative role of cattle in rebalancing social order.

Social Cohesion and Trust:

- Unlike coins, which rely on centralised minting and standardised value, cattle required communal agreement on their quality and worth. A milch cow’s value depended on its health, age, and productivity, necessitating trust and transparency in transactions. This system fostered social cohesion, as disputes over value would have been resolved through communal norms and legal frameworks, as seen in Mac Aodhagáin’s treatise.

- The use of younger cattle for smaller transactions (e.g., a dartaid at ⅛ the value of a milch cow) allowed for granular economic interactions, akin to modern fractional currency. This flexibility ensured that even minor obligations could be settled without resorting to barter’s inefficiencies.

Environmental and Practical Alignment:

- Cattle were ideally suited to Ireland’s landscape and economy. The island’s lush pastures supported large herds, and cattle provided milk, meat, hides, and labour, making them a multifaceted asset.

- The valuation system, with its focus on reproductive potential (e.g., samaisc at ½ a milch cow’s value due to its nearing maturity), reflects an intimate understanding of agricultural cycles.

- The inclusion of sheep, fleeces, and grain for lesser values further demonstrates practicality, allowing the system to accommodate a range of economic needs, from major fines to everyday exchanges.

Transition and Legacy:

- The introduction of coinage by Sihtric III in AD 1000 marked the beginning of a slow transition, but the persistence of cattle as currency for centuries afterwards highlights their entrenched role.

- Even as coins became more common, cattle likely retained symbolic and practical importance in rural Gaelic regions, where access to minted money was limited.

- The cattle-based system left a lasting cultural legacy, evident in Irish literature and folklore, where cattle raids (e.g., the Táin Bó Cúailnge) symbolise wealth and power. This underscores how deeply cattle were woven into the fabric of Irish identity.

Conclusion:

The cattle-based currency system of medieval Ireland, with its detailed valuation of younger cattle (samaisc at ½, colpthach at ⅓, dairt at ¼, and dartaid at ⅛ the value of a milch cow), was a dynamic and resilient economic framework.

It balanced practicality with cultural significance, aligning value with agricultural realities while fostering social cohesion and resisting external monetary systems. Far from being a primitive stopgap, this system was a sophisticated reflection of Gaelic society’s priorities, demonstrating that wealth, in the form of living cattle, was inseparable from life itself.

The eventual shift to coinage, while inevitable, could not erase the enduring imprint of cattle on Ireland’s economic and cultural landscape.

Sources:

D.A. Binchy (ed) Críth Gablach. Mediaeval and modern Irish series XVII.

Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, Dublin, 1941.

Fergus Kelly, A Guide to Early Irish Law (Early Irish Law Series III).

Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, Dublin, 1988.

Fergus Kelly, Cattle in Ancient Ireland: Early Irish Legal Aspects, in Cattle in Ancient and Modern Ireland Farming Practices, Environment and Economy, Cambridge, 2016.

W. O’Sullivan, The Earliest Irish Coinage. J R Social Antiquities Ireland 79: 190–235, 1949.