Ireland’s Brehon Laws teach us about the central importance of the family, the role of children, and the rights of women in ancient Irish and medieval history.

The Brehon Laws of Ireland

Prior to the Anglo-Norman invasions, Ireland was home to between 80-140 independent petty kingdoms called túatha. A person’s idea of nationhood was local to their home túath and kin-group (fine). Each túath had its king elected from among its noble grades, each had their own customs and traditions, styles of dress, particular songs and legends making each túath culturally and politically distinct in character from the next. Early Irish history is a logbook of the allegiances, battles, and triumphs of these kingdoms and the families that comprised them.

At the backdrop of this seemingly bitty social order a golden thread of justice held the fragments of society together; a set of laws and customs that were common to all across the land, long since established, just, fair and practical. These were the customary practices that had developed through the interactions of free people over extended periods of time until becoming the accepted standards of society, the social norms and principles that were said to have been around since “time immemorial” or to be “as old as the rocks themselves”.

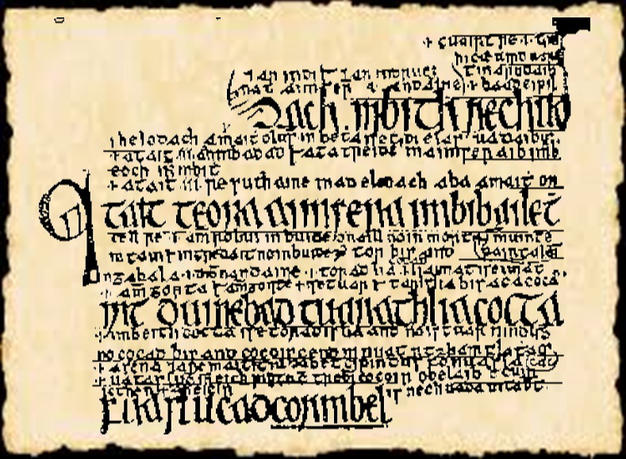

They are known today as the Brehon Laws because they were kept secure by a special educated class called britheamh in Gaelic (the anglicised form of which is ‘brehon’). Unlike modern judges, the opinions of brehons were not backed up by the police, a prison system or even legislation. Instead, their judgments carried weight because of the high regard placed on them by the people themselves. Any defendant who ignored a true judgment arrogantly risked being shunned and ostracised by his túath.

An Fine – The Kin-Group

At the centre of the social order we find the family as the primary social unit; the fine (pr. finna) and septs that made up the tribal nations of Old Ireland. Conceptually, the family-unit was extended over three distinct levels based on proximity of relations sharing a common ancestral-father.

Of these, the largest unit was the iarfine, or ‘after-kin’, comprised of all descendants sharing a common great-great-grandfather.

Next, the derbfine, or ‘true-kin’, which was considered to be the most important. Under the Brehon Laws parties to legal proceedings were not treated as individuals but rather as members of their wider kin-group. For the purposes of law, therefore, the whole derbfine was treated as a single legal entity. All kinsmen of this group were duty bound to remedy all wrongdoings, whether committed by or against their members.

Finally, the gelfine, or ‘bright-kin’, was the close family made up of all descendants sharing a common grandfather.

It is from all these relationships and the clear importance placed on the family that we get the distinctly Gaelic Ó and Mac prefixes of many Irish surnames; corresponding to the Grandson(s) of X or the Sons(s) of Y respectively.

Child-Rearing and Fosterage

The entire kin-group was responsible for ensuring their offspring were raised according to the accepted customs of the túath, to make sure they were educated in the skills suiting their station in life, and to guide them into adulthood as respectable dignified members of society. They had a serious interest in making sure this was achieved. Aside from the potential financial liability in having to pay for a kinsman’s wrongdoings, the family honour was also ever on the line.

It was common for children to be raised according to the old custom of fosterage where family allies, distant relatives, or tutors in education, would raise the children until early adulthood. This custom forged great bonds between foster-kin and the families of foster children; a fact that is supported by the Brehon Laws which awarded compensation to a victim’s foster-kin, and by the Mythological Sagas where we find numerous instances of fosterage mentioned.

The Status of Women

While the status of women in early Ireland was arguably better than any contemporary European society; and while we have references to powerful Queens and Goddesses in our mythologies; and while the island itself is even traditionally named after some of these Goddesses (e.g. Éiru, Banbha, Fodhla); it would be a disservice to history to state that women were in all respects ‘equal to men’. As you might expect the situation was more complex than that.

We find, for example, that in ordinary household life a woman’s social status was legally based on her closest male relative’s – whether her father, husband or adult sons. Though this served to provide her with some legal and financial social protections, she was in turn limited in her own legal capacity; she was restricted from entering contracts independently and could only give testimony at law in certain limited circumstances.

On the flip-side, however, the Brehon Laws also stated that wives held the “right to be consulted on every subject”. Crucially, women could choose who they married, were never considered to be their father’s or husband’s property, owned their own wealth and retained their property in the case of divorce – which they themselves could initiate on certain grounds; and, importantly, women were not confined to the household station in life.

Women could access higher education and develop their skills and expertise to become eligible to join any of the high-grade professions, and, through their own merit and excellence, begin to increase their social status in like manner as the men. We know, for instance, that there were female druids, brehons, poets, musicians, and doctors, etc. A woman who attained a higher grade than that of her closest male kin began to operate independently within society according to her own status.

A legal tale from early Irish mythology

This short story from the Lebor Gabhála Érenn (Book of the Takings of Ireland) illustrates the high position women held in Ireland from the earliest times.

One day, the story goes, the leader of an early group of inhabitants of Ireland, Partholón, took off to survey the rich Irish landscape, leaving his wife Delgnat at home on their little island situated on a coastal inlet of County Donegal. While away, Delgnat sleeps with one of her servants, an extended kinsman of a lower grade named Topa. Adding insult to injury the adulterers share a drink from Partholón’s personal cup using his golden straw.

Partholón later returns from his excursion with a great thirst and calls for a drink. Placing the golden straw to his lips he instantly learns of the betrayal that had taken place. In a fit of vengeful fury he slays Topa along with Delgnat’s prized hound, Saimer. Partholón had taken the law into his own hands and committed an offence against his wife greater than the injury he had himself suffered – justice demanded a remedy. Consulting the wisdom of a Brehon, damages were awarded against the husband in favour of the wife, thus establishing legal precedent.

“And that, without deceit, is the first judgement in Ireland: so that thence, with very noble judgement, it is the right of his wife against Partholón.”

As restitution, Delgnat claimed the island and renamed it Inish Saimer (Saimer’s Island) in honour of her dog – and it remains this name today.