The Senchus Mór (pronounced: shen-kus moor) is one of the most important legal texts from early Ireland and it means the ‘Great Ancient Tradition’.

However, the most all-encompassing word for this body of law is Fénechas which means the ‘law of freemen’ or the ‘free land-tillers’.

Claimed as the first undertaking of transferring the oral traditions into writing, the legendary account attributes the writing of the Senchus Mór to Saint Patrick during the reign of King Laeghaire in the 5th century. Upon Laeghaire’s request, Saint Patrick was commissioned to oversee the transposing of the laws to writing. Calling an assembly of nine representatives from various classes of society the idea was to also bring the laws into conformity with the Catholic Church and so they rejected any customs that contradicted prevailing ecclesiastical laws.

In attendance at the gathering there were three kings of whom Laeghaire himself was one, three ecclesiastics of whom Patrick was one, and three poets and antiquarians of whom there was Duftach, Laeghaire’s chief poet. This project would take three years to complete and would finally fill five volumes. However, given that the text is actually dated to have been written in the 8th century, it is much more likely that Saint Patrick had nothing to do with the writing of the Senchus Mór and, by attributing it to him, the actual authors were trying to add a sense of clerical authority and legitimacy to a text that was really written several hundred years after he had died. In any event, the Senchus Mór remains one of the most integral texts in our modern understandings of early Irish law and society.

The Senchus Mór covers a range of topics generally considered to be related to civil law. These include the rules of legal procedure, a process of legal redress known as athgabhail or distress, the regulations around the use of fasting as a legal remedy, fosterage of children, marriages, and pledges, and, interestingly, it structured the significant custom of stock-taking i.e. where a noble loans property to clients in exchange for tribute, upon which the entire social hierarchy was based.

Sadly, we have been unable to salvage a full copy of this manuscript from the fragments of a culture wrecked by colonisation. But, thanks to the efforts of the Brehon Law Commission (c. 1852), we do have access to the first, second, and a portion of the third volumes. Globally un-rivalled in its fullness, it gives an outstanding and rare perspective into the institutions, customs, beliefs, language, and culture of Irish society in ancient times.

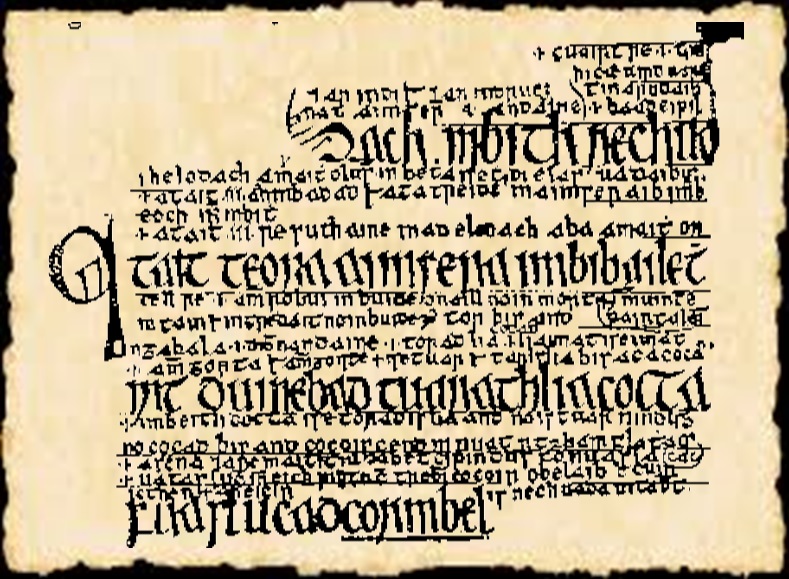

Some facsimile specimens do remain. One of the most prominent of these is featured in the images on our homepage. It is not read in normal fashion beginning at the top left of a page and working through each line in turn, rather it begins around the middle of the paragraph and from here lines are read from above and below in a way that gives the impression that the line or priniciple being discussed is literally being expanded upon.

In the image sample on the homepage, assuming each line is numbered 1-17 it would begin at line no. 8 which itself comments on the line of large text beneath. From here read no’s. 7 – 6 – 5, parts of 4 and 3 (separated by a curved line), and conclude with no’s. 2 – 1, thus reading ‘up’ the paragraph from the inial starting point at line no. 8. Once competed the process begins again at line no. 9, sometimes reading upward, sometimes downwards.