Nature and The Law

Among the myriad features that distinguish the early Irish native Brehon laws from other legal systems, its deep reliance on and connection with nature is one of the most intriguing. We are not talking about Natural Law in the sense commonly thought of or studied today, but rather a reliance on the laws of nature, that is, on the permanent and purposeful principles of nature observable to all.

In pronouncing their judgments, a Brehon had to be knowledgeable in the interpretation of the cáin and urradhus, the common and local laws, they must be able to construct their judgment in the form of poetry, and this had to mirror the truths observable in nature. All these factors would lend weightiness and credibility to the Brehon’s judgments; which was necessary in a time when there were no executive enforcement mechanisms to enforce legal outcomes.

The concept of “true” versus “false” judgment was central to this legal framework, where a “true” judgment was considered one that was aligned with the inherent principles of nature and fairness. It is as though justice could be felt and perceived as a real force, that one would indeed know it when they see or when they feel it. In the Story of King Cormac, the boy Cormac’s judgment was better because he relied on an observable principle in nature. Rather than a simple swap, the sheep as compensation paid for the crops it had damaged, as the presiding judge and present king decreed; Cormac decried this ‘false judgment’ by reminding all present “as the fleece grows on the sheep, so does the fleece grow on the land,” the wool of the sheep in exchange for the crops of the land.

All who heard this deemed Cormac’s to be the true judgment. Cormac’s reliance on the laws of nature, that is, on a knowable and observable principle found within the natural world, rendered his determination self-evident in the ears of those who heard it.

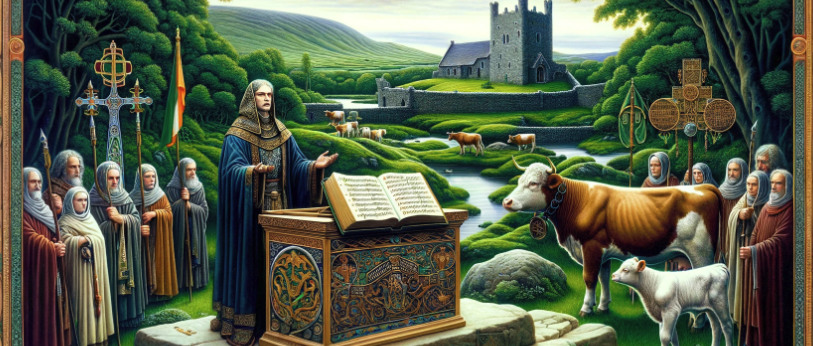

Another lively story to illustrate the interplay of law and nature in the minds of the early Irish can be found in the phrase “To Every Cow Its Calf.” This principle underscores the Brehon emphasis on rightful ownership and the natural bond between creation and creator. This story provides a slightly more historical example of how Brehon law used analogies from the natural world to resolve conflicts; reflecting the broader cultural and ethical milieu of early Irish society, and highlighting how the Brehons viewed the world around them as a foundation for justice and social harmony.

Early Christian Ireland

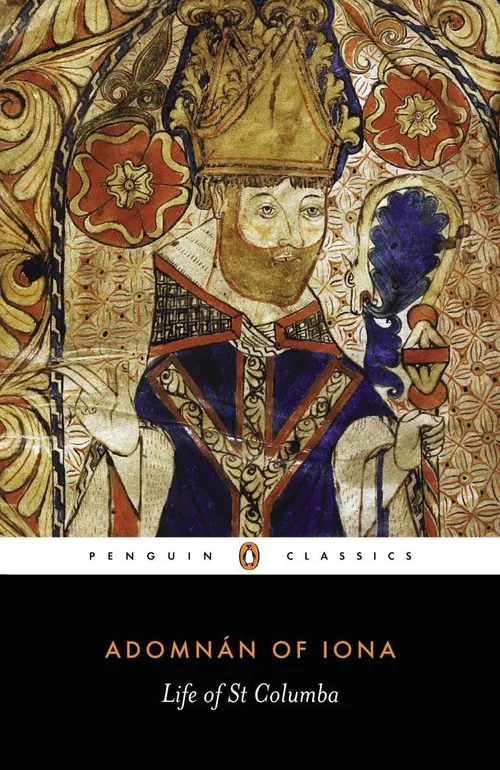

| The backdrop to the renowned dispute between St. Finnian and St. Colmcille is vividly chronicled in Adomnán’s “Life of Columba.” Adomnán, a ninth Abbot of Iona and St. Columba’s biographer, provides a crucial historical and cultural context, illuminating the lives and times of these prominent figures in early Christian Ireland. |

During the 6th century, Ireland was undergoing a profound transformation marked by the spread of Christianity, which introduced new religious and cultural dynamics into the traditionally pagan society. Monasteries were central to this change, serving not just as religious centres but also as hubs of learning and manuscript production. It was within this setting that the relationship between Finnian and Columba developed, rooted in a mentor-pupil dynamic. St. Finnian, an established scholar and religious figure at the monastery of Moville, was one of the early teachers of St. Columba, who later became a leading figure in the Irish monastic movement.

The relationship between these two figures was complex, blending reverence, scholarly pursuit, and eventual conflict. Their dispute over the copying of a manuscript—an act that today might fall under intellectual property rights—echoes the broader struggles within the rapidly evolving Christian community in Ireland. This contention not only involved personal and monastic rivalries but also highlighted the emerging conflicts between old Brehon traditions and the new Christian doctrinal influences, where the interpretation of ownership and entitlement began to take new forms.

The Dispute

The central conflict arose when Colmcille (Columba), born into the prestigious O’Neill dynasty, then at the monastery under St. Finnian at Moville, surreptitiously copied a psalter, a book of Psalms, which Finnian held. Upon discovering this, Finnian demanded the return of the copied manuscript, arguing that the intellectual output derived from his original manuscript belonged to him. Colmcille’s refusal to surrender the copy escalated the dispute to a matter requiring legal resolution, prompting its referral to the High King Diarmait Mac Cerbaill.

The trial itself was a dramatic manifestation of the tensions between old Brehon legal traditions and the Christian ethical framework that was beginning to take hold in Ireland. Diarmait Mac Cerbaill, applying the principles of Brehon law, sought to find a resolution that adhered to these traditional legal codes, which often used nature-based metaphors to elucidate rightful ownership and justice.

MacCerbaill’s judgment, “to every cow its calf and to every book its copy,” underscored a fundamental principle of Brehon law: the creator or rightful owner retains inherent rights to their property or its derivatives.

This ruling not only resolved the dispute in favour of Finnian by upholding the principle that the original owner of a manuscript also owned any copies made from it but also highlighted the evolving interpretation of ownership and copyright in a shifting cultural and legal landscape. The judgment, steeped in the wisdom of natural law, resonated deeply, reflecting the holistic approach of Brehon law in seeking to align human affairs with the observable truths of the natural world.

The Battle of Cúl Dreimhne

The judgment rendered by King Diarmait Mac Cerbaill did not settle the matter peacefully, as St. Colmcille, deeply aggrieved by the decision, found himself at odds not only with St. Finnian but with the ruling authority. This conflict ultimately led to one of the more tragic consequences of medieval Irish disputes: the Battle of Cúl Dreimhne.

The historical context surrounding the Battle of Cúl Dreimhne, fought in 561 AD, is interwoven with the dense tapestry of Irish clan politics and the burgeoning influence of Christian monastic establishments, which were increasingly becoming power centers. The battle was not merely about a disagreement over a book but was emblematic of the larger tensions between the secular and ecclesiastical powers vying for influence in Ireland. St. Colmcille, leveraging his royal connections and considerable influence as a churchman, was able to rally supporters, likely driven by a combination of personal loyalty to Colmcille and the broader political ambitions of the northern clans against their rivals.

The consequences of the battle were profound. While historical records vary, it is widely accepted that the conflict resulted in significant loss of life, casting a shadow over Colmcille’s legacy. The scale of the violence and the resultant casualties led to a deep personal crisis for Colmcille, who, according to some accounts, was held morally responsible for the deaths incurred due to his refusal to accept the judgment.

The Aftermath – Establishing Iona the Island Monastery

| In the aftermath, Colmcille’s position in Ireland became untenable, prompting his self-imposed exile to Iona in Scotland. This move marked a significant shift in his life and mission. In Iona, Colmcille established a monastery that would become one of the most influential centers of religious and cultural learning in the region, spreading the Christian faith across Scotland and the north of England. The Battle of Cúl Dreimhne thus serves as a pivotal moment not only in Colmcille’s life but also in the broader narrative of Irish and Scottish history. |  |

Final Thoughts

The Brehon law’s maxim “to every cow its calf” and its application in the dispute between St. Finnian and St. Colmcille illustrate the early Irish people’s deep reverence for both law and nature, and that law, if founded upon nature, must by definition be true. “To every cow its calf” acknowledges there is an intrinsic connection between creation and creator, and serves as a foundational concept in understanding the Brehon legal system’s reliance on natural phenomena to frame their legal judgments. This notion holds to the view that law itself should be as inherent and self-evident as principles observable within nature. Symbolically, the phrase reflects the deep cultural and ethical considerations of ancient Irish society, emphasizing that justice should follow the natural order of things, where every creation (or product) inherently belongs to its creator.

The judgment in the dispute also prefigured modern concepts of copyright law. It outlined the basic notion that the creator, or in this case, the original owner of a manuscript, retains rights over reproductions of their work. This early interpretation of copyright, rooted in the specifics of a 6th-century monastic dispute, underscores how ancient legal principles have influenced broader legal concepts that continue to evolve today.

The battle between Finnian and Colmcille and the resultant judgment by King Diarmait Mac Cerbaill illustrate the complexities of applying traditional laws. The principles of Brehon law, particularly as illustrated in this case, offer valuable insights into the interplay between law, morality, and society — insights that continue to influence legal thought and the interpretation of justice in the modern world.

To every cow it’s calf… and to every land it’s law. Our friend should have argued, not fought, and we are the worse for it despite our long tenure upon this island beneath the stars

I hope only that this comment qualifies a mug to me, which otherwise would cost enormous treasure, which I may only pray one day to offer you again upon the foundation here set by these my words

😀 I don’t really need a mug, but then nodody turns down a gift, or surely nobody I know of