In the waning years of the 19th century, an unusual group of treasure hunters descended upon the Hill of Tara, one of Ireland’s most revered ancient sites. Known as the British-Israelites, they were not Israelis as some might assume from a modern lens, but rather a curious sect from Britain, driven by a fervent belief that the Anglo-Saxon race was descended from the Lost Tribes of Israel.

Between 1899 and 1902, they brought shovels, picks, and even dynamite to Tara, convinced that beneath its grassy mounds lay the Ark of the Covenant—the legendary chest said to house the tablets of the Ten Commandments. What unfolded was a clash of ideologies, a spectacle of protest, and a peculiar chapter in Ireland’s cultural history.

The Mounds at Tara

“The Ark of God, adorned with Gold,

Shall yet be found at Tara;

The law on stone which it doth hold

Shall yet be found at Tara;

Engraven there by God’s own hand,

And hid away at His command,

Joy will reign throughout the land

When they are found at Tara.”

The British-Israelites and Their Quest

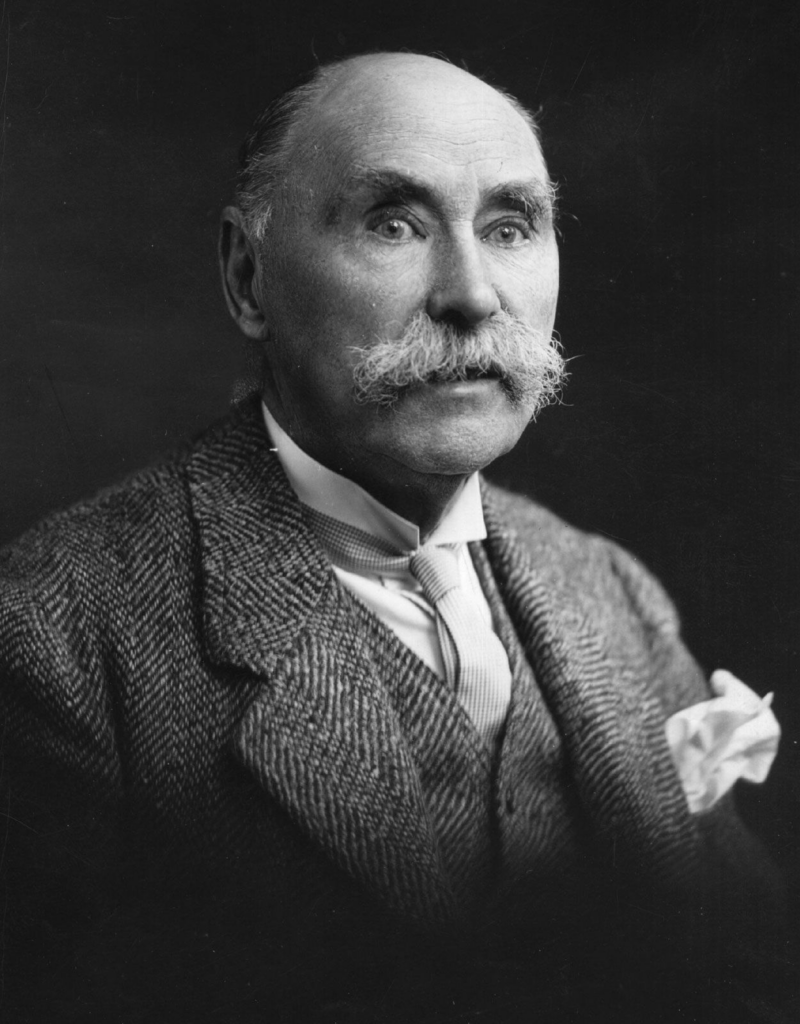

The British-Israelites were led by Edward Wheeler Bird, a retired Anglo-Indian judge who founded the British-Israel Association of London. Their ideology was a heady mix of biblical literalism, racial superiority, and imperial ambition. They posited that the British Empire’s global dominance was divinely ordained, a fulfillment of God’s promise to the descendants of Israel. Central to their theology was the notion that the Ark of the Covenant, lost to history after the Babylonian conquest of Jerusalem, had somehow made its way to the British Isles. And where better to hide such a sacred relic than Tara, the ancient seat of Ireland’s High Kings, which they saw as a “resuscitated Jerusalem” and the spiritual birthplace of the Anglo-Saxon nation?

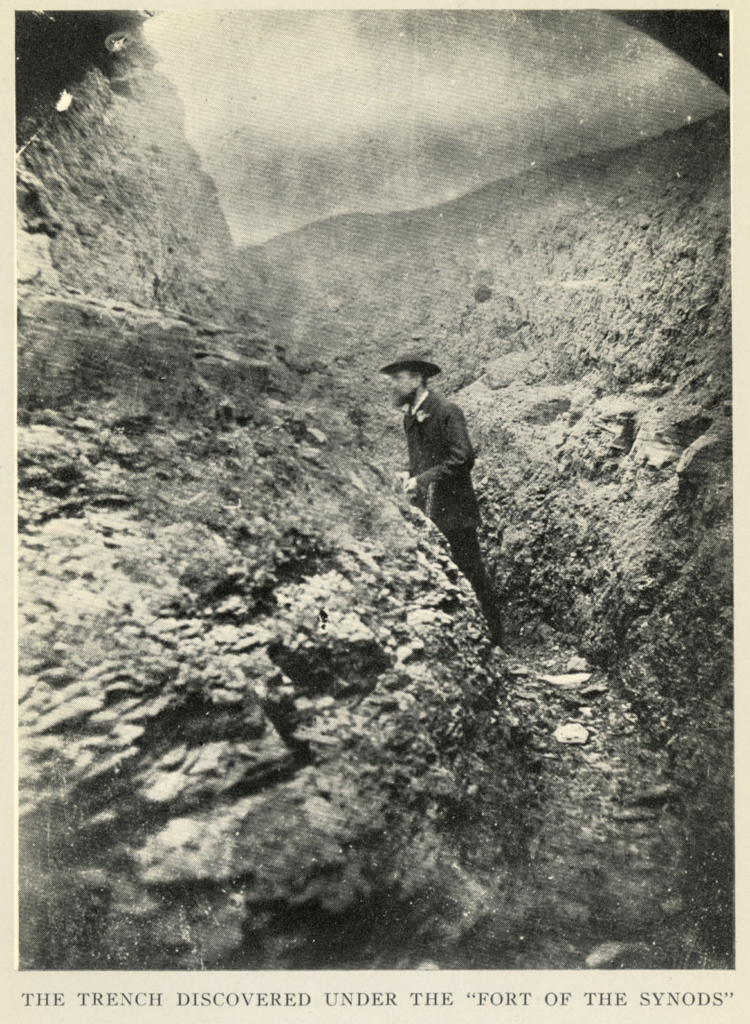

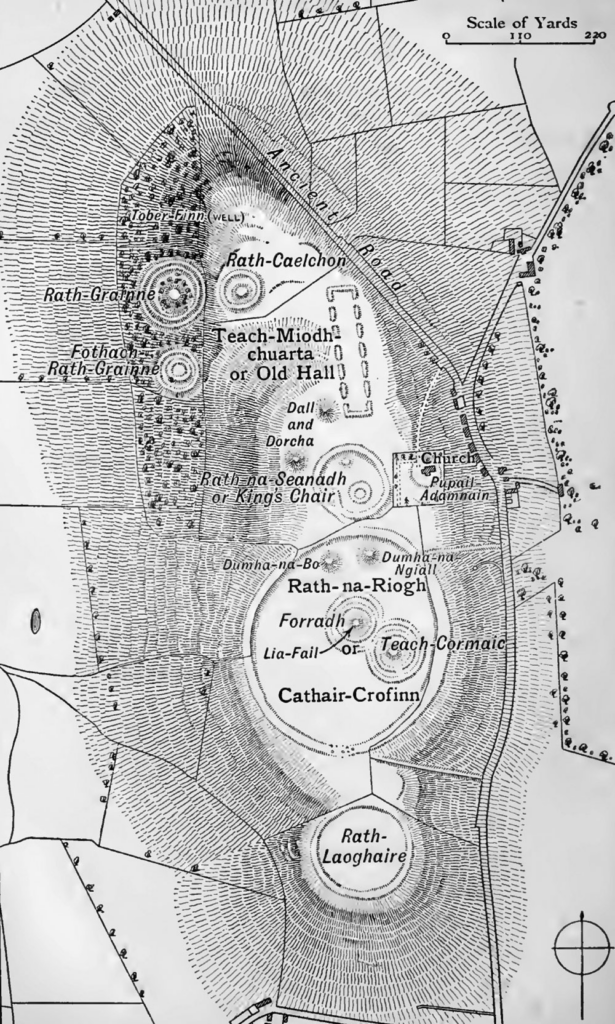

Armed with this conviction, the British-Israelites began digging at the Rath of the Synods, one of Tara’s prominent earthworks, in 1899. Their methods were far from scientific—rumors persist that they resorted to dynamite to blast through the hill, though hard evidence of explosives remains anecdotal. They were spurred on by a cryptic notion they called the “Great Irish-Hebraic-cryptogramic hieroglyph,” a supposed hidden code linking Tara to biblical prophecy. Freemasonry, with its shared symbolism of the Ark, also wove its way into their narrative, adding another layer of mystique to their mission.

Their efforts were bankrolled by Gustavus Villiers Briscoe, a local landlord who, swayed by their promises or perhaps their purse, allowed the excavations to proceed. As the British-Israelites toiled, Briscoe reportedly sat by, sipping whiskey, indifferent to the desecration of a site many Irish held sacred.

Their slogan “A.E.I.O.U.Y.” stood for:

“Angliae Est Imperare Orbi Universo Yisraelan”

It is for the Anglo-Israelites to dominate the Universe.

The Masonic Connection

The British-Israelite excavations at the Hill of Tara (1899–1902) were not only a product of their idiosyncratic belief in Anglo-Saxon descent from the Lost Tribes of Israel but also carried a subtle yet significant thread of Freemasonic influence. This connection, while not the driving force of their mission, added a layer of symbolic resonance to their search for the Ark of the Covenant, intertwining their racial theology with Masonic traditions.

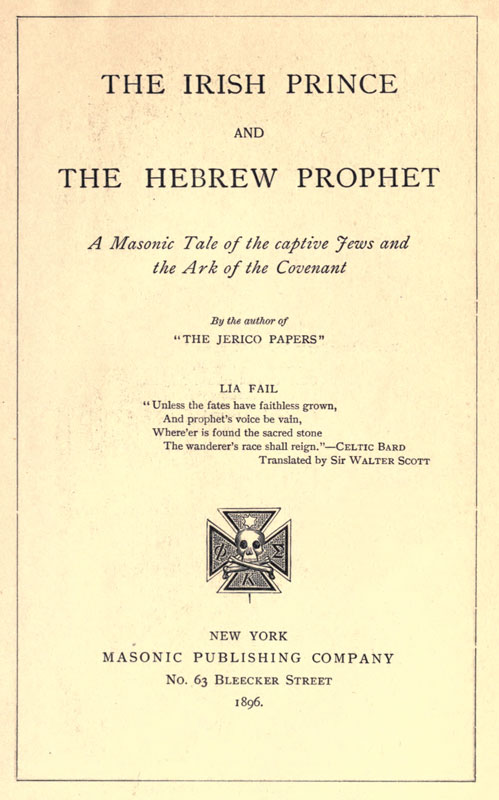

“The Irish prince and the Hebrew Prophet; a masonic tale of the captive Jews and the Ark of the Covenant.”

Published in 1896, this novel describes the burial of the Ark at Tara, at Chapter XII.142, pp.137-145.

Freemasonry, a fraternal organization with roots in the 17th century, shares with British-Israelism a fascination with the Ark of the Covenant as a potent symbol. In Masonic ritual, particularly within the Royal Arch degree, the Ark is revered as a representation of divine presence and covenant, often linked to the rebuilding of Solomon’s Temple—a narrative that echoes the British-Israelites’ vision of Tara as a “resuscitated Jerusalem.” Mairéad Carew, in Tara and the Ark of the Covenant, notes that the Ark served as a “common symbol” for both groups, bridging their ideologies. For the British-Israelites, finding it at Tara would affirm their claim as God’s chosen people; for Masons, it reinforced a mystical heritage tied to ancient wisdom.

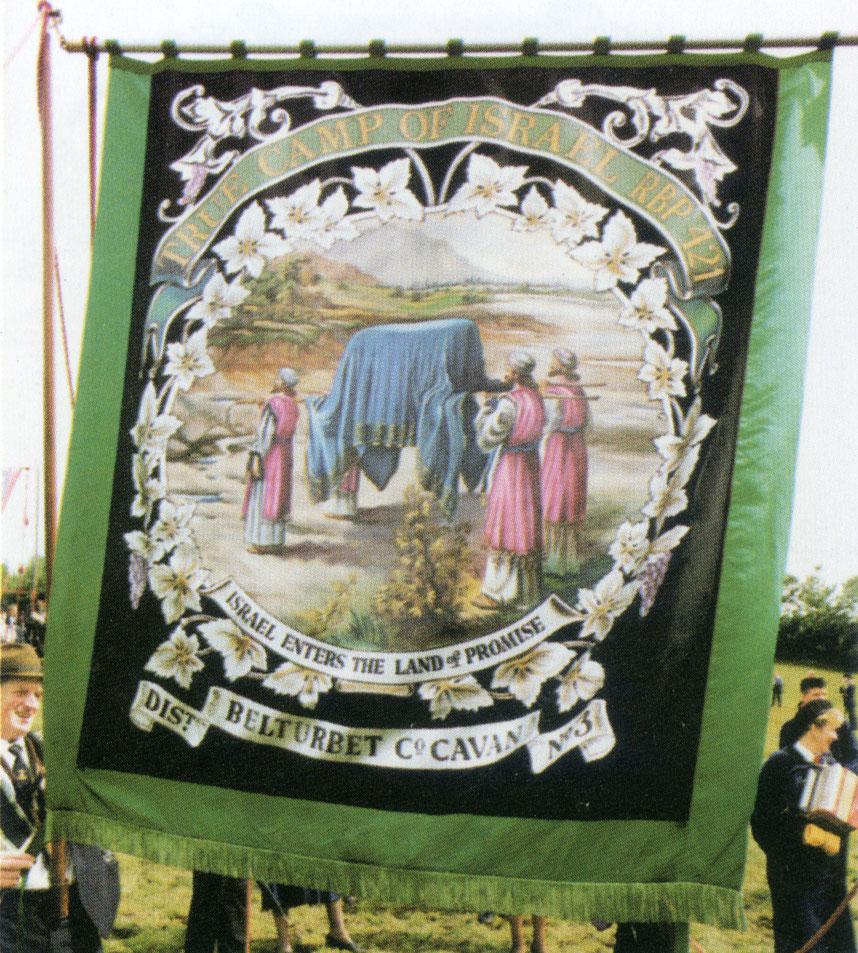

The Ark of the Covenant is displayed on a banner of the Imperial Grand Black Chapter of the British Commonwealth,

or simply the Royal Black Institution, a group related to the Orange Order.

Photo: Neil Jarman, from his book Displaying Faith (1999).

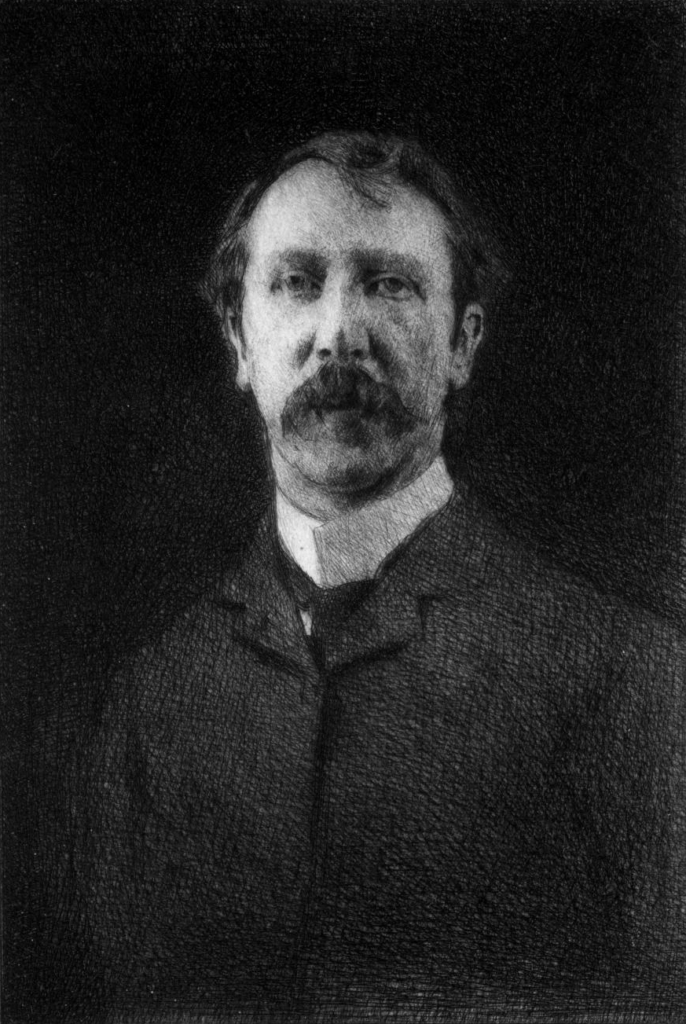

Though the British-Israelites were predominantly Protestant in outlook, Freemasonry’s interdenominational nature allowed it to intersect with their movement. R.A.S. Macalister, a prominent archaeologist and Freemason himself, critiqued their Tara venture in his 1931 book Tara: A Pagan Sanctuary of Ancient Ireland, dismissing their theories as “utterly removed from normal sanity,” suggesting they deserved pity rather than scorn. Yet his own Masonic background highlights the overlap: both groups drew on esoteric interpretations of biblical history, albeit with different ends. The British-Israelites’ “Great Irish-Hebraic-cryptogramic hieroglyph”—a supposed code linking Tara to the Ark—mirrored the Masonic penchant for cryptic symbolism, suggesting a shared intellectual undercurrent.

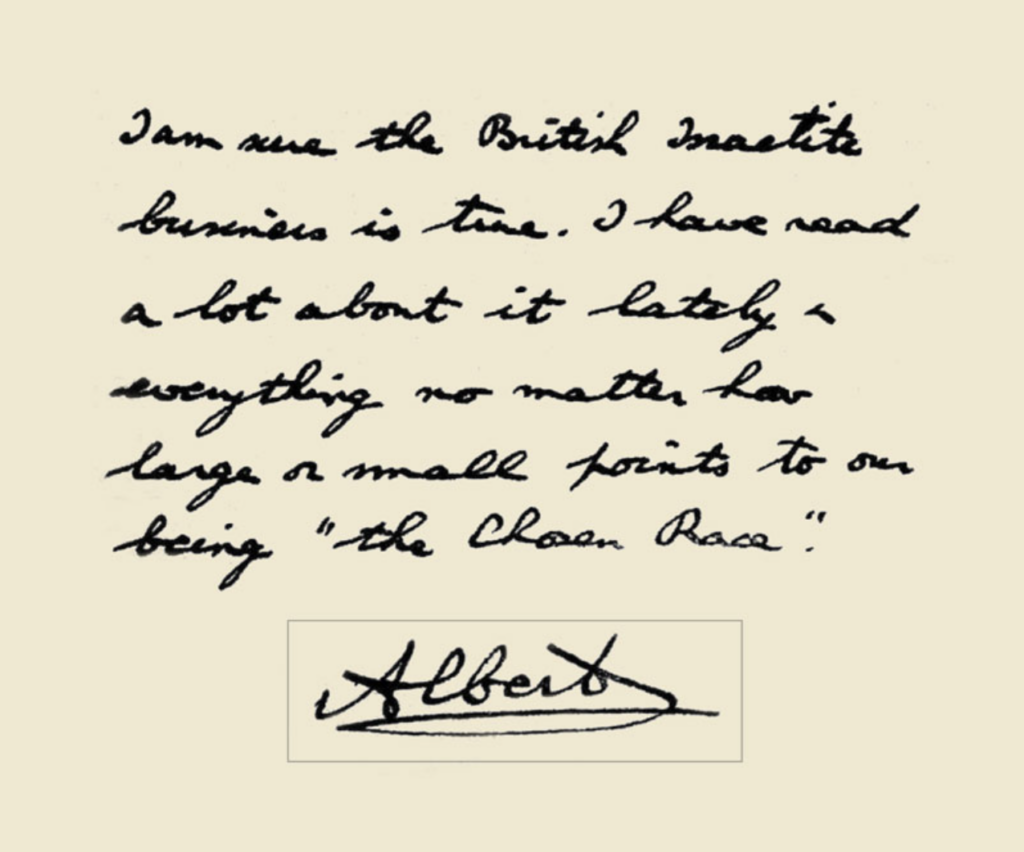

Historical figures amplify this link. The future King George VI, then Duke of York, wrote the following letter in 1922:

“I am sure the British Israelite business is true. I have read a lot about it lately and everything

no matter how large or small points to our being the ‘chosen race’”.

(Source: John Windsor. “Cashing in on the royal mail.” Weekend Independent (London, England) 6 Apr. 1996: at p.6.)

Charles Groome, a key British-Israelite at Tara, leaned on a mishmash of Egyptian hieroglyphs and medieval poetry to pinpoint the Ark’s location, a method reminiscent of Masonic fascination with ancient mysteries. Meanwhile, the broader British-Israel movement attracted figures like Edward Wheeler Bird, whose leadership paralleled the hierarchical structure of Masonic lodges. Though not all British-Israelites were Masons, the overlap in membership and ideas—especially among Protestant elites—lent their Tara quest a Masonic flavor, blending imperial ambition with ritualistic undertones.

This connection, however, remained secondary to their racial and biblical agenda. The British-Israelites’ primary aim was to validate their Anglo-Saxon supremacy, not to advance Masonic goals. Still, the Masonic thread enriched their narrative, casting Tara as a site where biblical prophecy, imperial destiny, and secret society lore converged—a notion that only deepened the eccentricity of their ill-fated dig.

Archaeology, Nationalism, and Symbolism

Tara, as the “site of Pupall Adamnain,” was tied to St. Adamnán (c. 624–704), who held a synod there and established a law in 697 protecting women and children in warfare, following the saints Ruadhan, Brendan, and Patrick.

The clash at Tara was more than a skirmish over a hill—it was a microcosm of broader tensions. The British-Israelites viewed Tara through an imperial lens, a site to bolster their narrative of Anglo-Saxon supremacy. For Irish nationalists, it was the potential capital of an independent Ireland, a link to a pre-colonial past. Both sides leaned on archaeology, history, and myth to stake their claims, but their methods and motives could not have been more different.

Charles Groome led the Tara dig, inspired by a mix of Egyptian hieroglyphs and an 11th-century poem linking Princess Tea Tephi (a Pharaoh’s daughter) to the Ark’s burial. While John Dillon, a landowner, documented the dig, noting bones, a golden bracelet, “altar stones,” Roman coins, and a rock-cut trench. Earlier, in 1810, two golden torcs, dubbed the “Tara Torcs,” found near the Rath of the Synods, were considered the “finest objects of the period.”

The 1950s excavations were led by Seán Ó Ríordáin.

At the time, Irish archaeology was shifting from gentlemanly antiquarianism to a more rigorous, scientific discipline. Leading archaeologists like R.A.S. Macalister (aforementioned), George Coffey, and Thomas J. Westropp joined the nationalists in opposing the dig, appalled by the British-Israelites’ reckless approach.

The 1899–1902 diggings destroyed much of the Rath of the Synod’s original shape, complicating modern identification due to later churchyard and townland boundaries. Comparatively, Seán Ó Ríordáin’s 1952–1953 excavations provided scientific clarity, contrasting with the British-Israelites’ disregard for collateral findings.

The Irish media, too, seized the story. As historian Mairéad Carew notes in her book Tara and the Ark of the Covenant, it marked the first time the press campaigned to protect a national monument. The episode highlighted a growing public consciousness about Ireland’s archaeological heritage, a sentiment that would echo through the 20th century as development threats loomed.

A Nation Rises in Protest

The British-Israelites’ assault on Tara did not go unchallenged. Far more than a historical site, Tara’s rolling hills and ancient earthworks stood as a potent symbol of Ireland’s past and a beacon for its emerging cultural nationalism. By the late 19th century, a cultural revival was sweeping the nation, championed by luminaries like Arthur Griffith, W.B. Yeats, Maud Gonne, Douglas Hyde, and George Moore. The diggers’ actions—perceived as both a desecration of a national monument and a colonial overreach—struck a deep chord, igniting a fierce resistance.

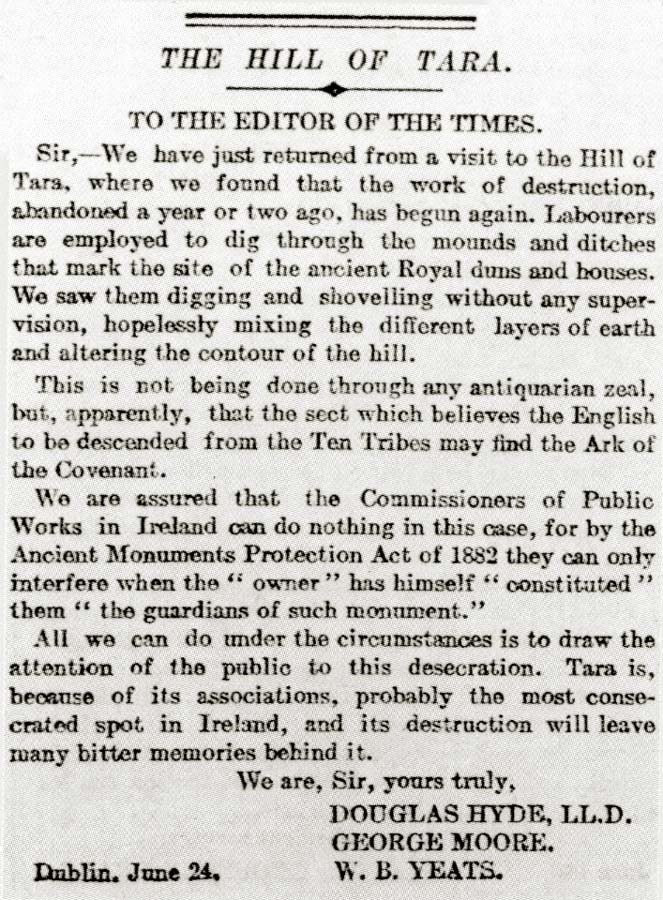

Letter published in The Times on 27 June 1902, signed by Douglas Hyde, George Moore, and W.B. Yeats.

(Source: Mairéad Carew, Tara and the Ark of the Covenant. (Dublin) Royal Irish Academy, (2003). at p.22.)

| Arthur Griffith, editor of the United Irishman and a future co-founder of Sinn Féin, spearheaded the opposition. On Christmas Day 1900, he joined forces with the flamboyant nationalist Maud Gonne to inspect the damage at Tara, condemning the destruction of Ireland’s heritage. Griffith rallied an impressive coalition, including Yeats, Gonne, Hyde, and Moore, whose protests culminated in a stinging letter to The Times of London. Signed by Hyde, Yeats, and Moore, it decried the excavations as an affront to “probably the most consecrated spot in Ireland.” |

| W.B. Yeats, the poet whose genius would later earn him a Nobel Prize, regarded Tara as a sacred emblem of Ireland’s soul, a place where myth and history intertwined to inspire a nation. Undeterred by a rifle-wielding enforcer who ordered him off the site, he stood resolute on the hill alongside Arthur Griffith, lending his commanding presence and lyrical voice to the cause. For Yeats, Tara was not just earth and stone but a wellspring of Ireland’s spiritual and cultural identity, a vision he would later weave into his poetry. His defiance in the face of threats underscored his belief that preserving Tara was a battle for Ireland’s very essence. |

| Maud Gonne, Yeats’s muse and a revolutionary in her own right, transformed protest into theater. After her initial visit with Griffith in 1900, she delivered a crowning act of defiance on July 13, 1902. Hijacking a bonfire prepared by landlord Gustavus Villiers Briscoe to celebrate Edward VII’s coronation, Gonne led 300 children to Tara, lit the pyre ahead of schedule, and sang “A Nation Once Again.” The flames roared as a bold rebuke to both landlord and empire, infuriating Briscoe and the police but etching Tara deeper into Ireland’s national consciousness. |

| Douglas Hyde, a scholar and future first President of Ireland, infused the protest with his deep commitment to Irish identity. As a founder of the Gaelic League, Hyde championed the revival of Ireland’s language and traditions, and his presence at Tara rallied public sentiment by framing the site as a cornerstone of that legacy. |

| George Moore, the acclaimed novelist and a sharp-eyed observer of Irish life, brought his own weight to the fight. Known for his wit and cultural critique, Moore stood shoulder-to-shoulder with Yeats and Hyde, co-authoring the Times letter to amplify their condemnation. His involvement underscored Tara’s significance as a touchstone for Ireland’s artistic and intellectual awakening, bridging the literary and nationalist spheres. |

Together, they elevated the defense of Tara into a defining moment of resistance, blending heritage with the stirrings of independence.

The Outcome and Legacy

Did the British-Israelites find the Ark? Unsurprisingly, no. After three years of digging, from 1899 to 1902, they left Tara empty-handed, their theories unproven and their reputation in tatters. The site bore scars from their efforts—trenches and disturbed earth—but its essence endured, a testament to its resilience and the resolve of those who fought to protect it.

The protests succeeded in halting the excavations, a victory for Griffith, Gonne, and their allies. William Bulfin, a contemporary writer and friend of Griffith, observed wryly that the British-Israelites “slept upon the safest mattresses in the country and fed on the fat of the land,” escaping the punishment lesser vandals might have faced. Yet their misadventure left a lasting mark, amplifying Tara’s status as a cultural touchstone.

British-Israelite ideas influenced the Christian Identity movement, which deems modern Jews imposters and claims a divine mandate for the “white race.” The Duke of York (future King George VI) endorsed British-Israelism in 1922, reflecting its peak influence (20,000 members by 1920). British-Israelites drew on 18th-century antiquarians like Charles Vallancey, while Irish nationalists evoked a Celtic millennium, both shaping Tara’s symbolic role.

In June 2018, British-Israelites brought a replica Ark to the Rath of the Synods, preaching to tourists as the site’s true inheritors. In the late 20th century, John Anthony Hill sought planning permission to dig at the Mound of the Hostages, echoing earlier quests.

In 2018, a replica of the Ark of the Covenant was brought to the Rath of the Synods

Today, Tara remains a place of earthworks and echoes, its power rooted in its history and the stories it holds. The British-Israelite episode, as chronicled by Carew, is a quirky footnote—a tale of zealotry, resistance, and the enduring pull of a sacred hill. It reminds us how even the wildest quests can spark moments of unity and defiance, shaping a nation’s identity in the process.

Bibliography

Books

- R.A.S. Macalister, Tara: A Pagan Sanctuary of Ancient Ireland (1931)

- Mairéad Carew, Tara and the Ark of the Covenant (2003)

- Robert G. Kissik, The Irish Prince and the Hebrew Prophet- A Masonic Tale of the Captive Jews and the Ark of the Covenant (1896) (available for download in our members’ library)

- Charles A.L. Totten, The Land and Legends of Innis Fail. New Haven: The Our Race Publishing Company, (1905), p.3