The legal system of Ireland before the arrival of the Normans was known as the Brehon Law. It was a complex and evolved system of law that reflected the intricacies of early Irish society. The responsibility of initiating legal action lay with the injured party or their kin to the fourth generation (derbfine). There were no juries, and almost any crime could be atoned for by the payment of a fine or compensation.

Sick maintenance was a crucial aspect of early Irish law, regulating the provision of care for injured persons until they were fully recovered. The provision of sick maintenance was enforced through pledges, sureties, and fines, with different provisions for children and adults.

Although sick maintenance was eventually replaced by other forms of compensation, its importance in early Irish society cannot be underestimated.

This article will explore early Irish manuscripts and modern writings to gain a deeper understanding of the approaches to medicine and medical practices in Ireland in times long since past. Along the way, we marvel at how far we have come and even see a little bit of ourselves in the anxieties of the past.

Healers and Hierarchies: Medical Practices in Ancient Ireland

While physicians in medieval Ireland occasionally compiled medical texts in Irish, many were translations or adaptations of Latin works. Despite this, medical scholarship in medieval Gaelic Ireland was on par with that practised on the continent, with evidence of Irish scholars travelling to European medical schools and bringing their learning back to Ireland.

According to D.A. Binchy, early Irish society was “tribal, rural, hierarchical, and familial.” The population was divided into about 120-160 kingdoms known as túath, with each having a population of about 3,000. The distinction was made between those who were privileged (nemed) and those who were not, as well as between the free (sóer) and the unfree (dóer). Each túath had a king (rí), an ecclesiastical scholar (ecnae), a poet (file), a historian (senchaid), a judge (brithem túaithe), and a physician (liaig).

Physicians from notable families were revered in tribes as skilled healers, often serving the ruling dynasty. Law texts such as Bretha Déin Chécht, Bretha Crólige, and Di Ércib Fola all deal with medicine (see below), highlighting its importance in ancient Irish society. The fees charged by physicians were based on the wounds sustained and the status of the patient.

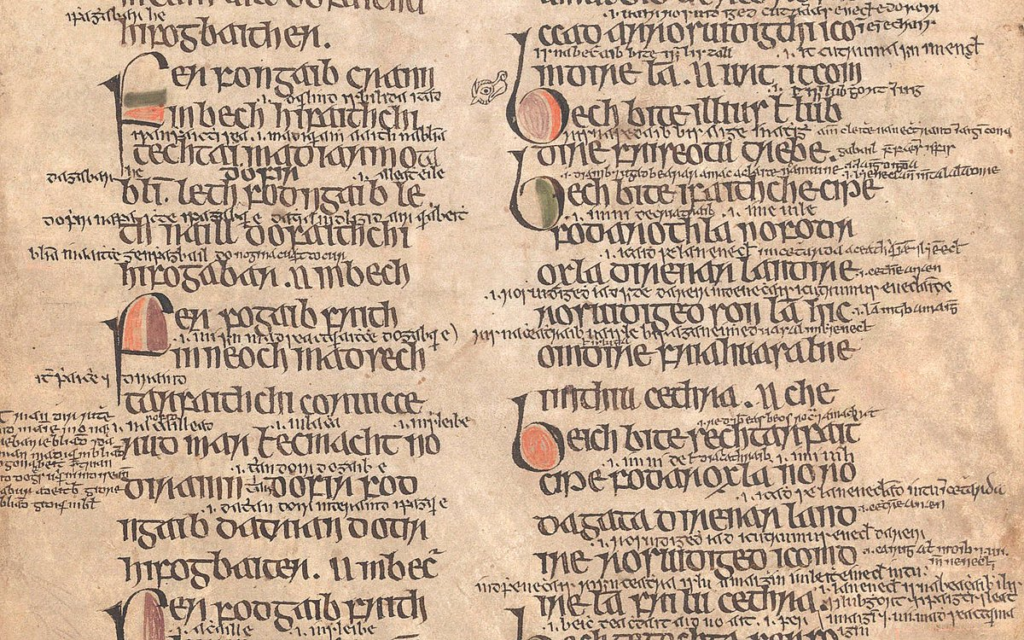

Primary manuscripts of ancient Irish law were transcribed between the 7th and 8th centuries, but compiled from the 13th to the 16th century at legal academies. Though written in Old Irish, later copyists added interlinear glosses, explanations, and commentaries in Middle Irish, making interpretation of the manuscripts challenging and translations uncertain. Christianity had a significant impact on Irish culture, but there was no parity before the law, with verdicts based on social status and law enforcement relying on surety, guarantee, and distraint methods based on equity and precedent instead of central enforcement. Despite this, the Brehon Law remains a vital part of Ireland’s cultural and legal heritage, providing insights into the complex society that thrived in Ireland before the Norman invasion. Books and manuscripts like these were stolen, lost, or destroyed following the Elizabethan conquest of Ireland, which put an end to the old Gaelic society. Early universities in Ireland, supported by the Gaelic lordships, fell asunder as the Elizabethan conquest proceeded.

“Sick Maintenance” and the Law of Liability in Early Ireland

Under the Brehon Laws, a person who unlawfully assaulted another was liable to pay a fine known as éric or corpdíre for the injury inflicted and an honour-price based on the status of the victim. Additionally, the offender had to provide sick-maintenance (othrus), which involved looking after the victim until he or she had recovered. Legally inflicted injuries, such as in self-defence, were not liable for othrus, however. These were called fuil slán, which meant “free blood”. For minor injuries, there was no obligation to provide othrus, but the perpetrator still had to pay the éric for the injury, which was calculated as a fraction of the fine for homicide.

When accused of inflicting an injury, a person was required to agree to abide by the rule of the court. The plaintiff’s allegations were admitted or denied by the defendant, and if denied, the plaintiff called witnesses and made a formal oath asserting the truth of his allegations, supported by three “oath-helpers.” The defendant then gave his version, supported by witnesses and “oath-helpers.” In this hierarchical society, the oath of a king outranked the oath of a freeman, and a churchman’s oath was considered the most reliable.

If a verdict could not be determined on the evidence, it was established by drawing lots, by ordeal, or by duel. Three pieces of wood called corcrann were used as lots to decide the verdict: “guilty,” “not guilty,” or “not proven.” The common ordeal used was fir coiri or the “proof of the cauldron,” where the suspect immersed his hand in a cauldron of hot water, and guilt was determined by the presence of scald marks after a specified time. A duel was conducted before witnesses, and the winner was deemed to have justice on his side.

Once a guilty party had been identified, the éric, the honour-price, and sick-maintenance costs were decided. The offender was required to provide for the victim’s medical expenses, suitable food and accommodation, and provide a substitute for the victim’s work.

Sick maintenance was treated differently for children and adults, with different provisions for each. If a child was injured, the culprit had to provide sick maintenance until they reached the age of seven, at which point the obligation shifted to the child’s family. For adults, the duration of sick maintenance was determined by the severity of the injury and the recovery period. In Bretha Crólige, a fine was substituted for sick maintenance for 12 categories of men and women. However, according to Críth Gablach, sick maintenance was already abandoned by 700 AD.

Sick maintenance, or “othrus,” was, therefore, an obligation placed on the person responsible for the injury, with specific laws regulating its provision. If a person was injured and still required nursing after nine days, the person responsible for the injury was obligated to provide sick maintenance. This involved taking the injured person to the house of a third party, usually a relative or a friend, and ensuring they received the necessary care and attention until they were fully recovered. The culprit had to cover all medical expenses, including suitable food and accommodation, and provide a substitute for the victim’s work during the recovery period.

To guarantee the performance of these obligations, pledges were exchanged between the culprit and the victim’s kin, with a surety (aitire) guaranteeing that the obligations would be discharged. The amount of the surety varied depending on the severity of the injury and the social status of the victim. If the culprit failed to fulfil their obligations, the surety would be liable for the outstanding sick maintenance expenses.

Despite the importance of sick maintenance in early Irish society, the Críth Gablach, a text on law and custom dating from the 7th century, states that sick maintenance had already been abandoned by the time of its writing. This indicates that the obligation to provide sick maintenance was not always strictly enforced and that other forms of compensation were being used instead.

Three Medical Texts From the Brehon Law Manuscripts: Bretha Déin Chécht, Bretha Crólige, and Di Ércib Fola

Bretha Déin Chécht, Bretha Crólige, and Di Ércib Fola are three important legal texts in Irish history.

Together, these three legal texts provide important insights into the medical practices and legal system of medieval Gaelic Ireland. They illustrate the importance of medicine in Irish society and the high status that was accorded to physicians. They also demonstrate the complex legal system that governed Irish society, which was based on a combination of customary law, Brehon law, and Christian law.

In Bretha Crólige, or the Judgement of Blood Letting, a compilation of laws dealing with compensation for homicide and injuries, a fine was substituted for sick maintenance for 12 categories of men and women. These categories included bards, brehons, poets, and druids, among others. The amount of the fine varied depending on the social status of the injured party and the severity of the injury.

The substitution of the fine for sick maintenance was meant to simplify the process of compensation and ensure that the injured party received fair compensation.

Bretha Déin Chécht

Bretha Déin Chécht, also known as the Judgement of Déin Chécht, is a legal text that deals with medical law in Ireland. It is named after Déin Chécht, a legendary Irish physician and judge, who is believed to have composed the text. The Bretha Déin Chécht details various medical practices, such as the treatment of wounds, dislocations, and fractures, and outlines the fees that physicians were entitled to charge for their services.

Bretha Crólige

Bretha Crólige, or the Judgement of Blood Letting, is another legal text that deals with medicine and the treatment of injuries. It is concerned specifically with the treatment of wounds caused by violence or warfare. The text outlines the procedures for assessing and treating such wounds, as well as the fees that physicians were entitled to charge for their services.

Di Ércib Fola

Di Ércib Fola, also known as Fine for Bloodshed, is a legal text that deals with the payment of fines for various types of bloodshed. It outlines the fines that must be paid for different types of injuries, ranging from minor injuries to more serious ones. The text also details the procedures for determining the severity of an injury and the corresponding fine that must be paid.

Resources and Additional Materials

Kelly, F. (1988). A Guide to Early Irish Law. Dublin: Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies.

Breatnach, L. (2010). A Companion to the Corpus Iuris Hibernici. Dublin: Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies.

Mac Niocaill, G. (1975). The Annals of the Four Masters. Dublin: Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies.

Ó Gráda, C. (2014). Irish History from 600-1600: A New Teaching and Learning Resource. Dublin: School of History, University College Dublin.