Aengus was asleep one night when he saw something like a young girl coming towards the head of his bed, and she was the most beautiful woman in Eriu.

He made to take her hand and draw her to his bed, but, as he welcomed her, she vanished suddenly, and he did not know who had taken her from him.

He remained in bed until the morning , but he was troubled in his mind: the form he had seen but not spoken to was making him ill.

No food entered his mouth that day.

He waited until evening, and then he saw a timpán in her hand, the sweetest ever, and she played for him until he fell asleep. Thus he was all night, and the next morning he ate nothing.

A full year passed, and the girl continued to visit Aengus, so that he fell in love with her, but he told no one. Then he fell sick, but no one knew what ailed him.

The physicians of Eriu gathered but could not discover what was wrong. So they sent for Fergne, Cond’s physician, and Fergne came.

He could tell from a man’s face what the illness was, just as he could tell from the smoke that came from a house how many were sick inside.

Fergne took Aengus aside and said to him:

‘No meeting this, but love in absence’.

‘You have divined my illness,’ said Aengus.

‘You have grown sick at heart and you have not dared to tell anyone.’

‘It is true. A young girl came to me. Her form was the most beautiful I have ever seen, and her appearance was excellent. A timpán was in her hand, and she played for me each night.’

‘No matter,’ said Fergne, ‘love for her has seized you. We will send you to Boann, your mother, that she may come and speak with you.’

They sent to Boann, then, and she came.

‘I was called to see to this man, for a mysterious illnes had overcome him,’ said Fergne, and he told Boann what had happened.

‘Let his mother tend to him,’ said Fergne, ‘and let her search throughout Eriu until she finds the form that her son saw.’

The search was carried on for a year, but the like of the girl was not found. So Fergne was summoned again.

‘No help has been found for him.’ said Boann.

‘Then send for the Dagda, and let him come and speak with his son,’ said Fergne.

The Dagda was sent for and came, asking ‘Why have I been summoned?’

‘To advise your son,’ said Boann.

‘It is right that you help him, for his death would be a pity. Love in absence has overcome him, and no help for it has been found.’

‘Why tell me?’ asked the Dagda. ‘My knowledge is no greater than yours.’

‘Indeed it is,’ said Fergne, ‘for you are king of the Síde of Eriu. Send messengers to Bodb, for he is King of the Síde of Mumu, and his knowledge spreads throughout Eriu.’

Messengers were sent to Bodb, then, and they were welcomed.

Bodb said ‘Welcome, people of the Dagda.’

‘It is that we have come for’ they replied.

‘Have you news?’ Bodb asked.

‘We have: Aengus son of the Dagda has been in love for two years,’ they replied.

‘How is that?’ Bodb asked.

‘He saw a young girl in his sleep,’ they said, ‘but we do not know where in Eriu she is to be found. The Dagda asks that you search all Eriu for a girl of her form and appearance.’

‘That search will be made,’ said Bodb, ‘and it will be carried on for a year, so that I may be sure of finding her.’

At the end of the year, Bodb’s people went to him at his house in Síd ar Femuin and said

‘We made a circuit of Eriu, and we found the girl at Loch Bél Dracon in Cruitt Cliach.’

Messengers were sent to the Dagda, then he welcomed them and said ‘Have you news?’

‘Good news: the girl of the form you described has been found,’ they said.

‘Bodb has asked that Aengus return with us to see if he recognises her as the girl he saw.’

Aengus was taken in a chariot to Séd ar Femuin and he was welcomed there. A great feast was prepared for him, and it lasted three days and three nights. After that, Bodb said to Aengus:

‘Let us go, now, to see if you recognise the girl. You may see her, but it is not in my power to give her to you.’

They went on until they reached a lake. There they saw three fifties of young girls, and Aengus’s girl was among them. The other girls were no taller than her shoulder; each pair of them was linked by a silver chain, but Aengus’s girl wore a silver necklace, and her chain was of burnished gold.

‘Do you recognise that girl?’ asked Bodb.

‘Indeed, I do,’ Aengus replied.

‘I can do no more for you, then’ said Bodb.

‘No matter, for she is the girl I saw. I cannot take her now. Who is she?’ Aengus said.

‘I know her, of course: Cáer Ibormeith daughter of Ethal Anbúail from Síd Uamuin in the province of Connachta.’

After that, Aengus and his people returned to their own land, and Bodb went with them to visit the Dagda and Boann at Brú; na Bóinne. They told their news: how the girl’s form and appearance were just as Aengus had seen. And they told her name and those of her father and grandfather.

‘A pity that we cannot get her,’ said the Dagda.

‘What you should do is go to Ailill and Maeve, for the girl is in their territory,’ said Bodb.

The Dagda went to Connacht then, and three score chariots with him. They were welcomed by the King and Queen there and spent a week feasting and drinking.

‘Why your journey?’ asked the king.

‘There is a girl in your territory,’ said the Dagda, ‘with whom my son has fallen in love, and he has now fallen ill. I have come to see if you will give her to him.’

‘Who is she ?’ Ailill asked.

‘The daughter of Ethal Anbúail,’ the Dagda replied.

‘We do not have the power to give her to you,’ said Ailill and Maeve.

‘Then the best thing would be to have the king of the síd called here,’ said the Dagda.

Ailill’s steward went to Ethal Anbúail and said

‘Ailill and Maeve require that you come and speak with them.’

‘I will not come,’ Ethal said, ‘and I will not give my daughter to the son of the Dagda.’

The steward repeated this to Ailill, saying:

‘He knows why he has been summoned, and he will not come.’

‘No matter,’ said Ailill, ‘for he will come, and the heads of his warriors with him.’

After that, Ailill’s household and the Dagda’s people rose up against the sid and destroyed it. They brought out three score heads and confined the king to Crúachu. Ailill said to Ethal Anbúail:

‘Give your daughter to the son of the Dagda.’

‘I cannot,’ he said, ‘for her power is greater than mine.’

‘What great power does she have?’ Ailill asked.

‘Being in the form of a bird each day of one year and in human form each day of the following year,’ Ethal said.

‘Which year will she be in the shape of a bird?’ Ailill asked.

‘It is not for me to reveal that,’ Ethal replied.

‘Your head is off,’ said Ailill, ‘unless you tell us.’

‘I will conceal it no longer then, but will tell you, since you are so obstinate,’ said Ethal.

‘Next Samhain she will be in the form of a bird. She will be at Loch Bél Dracon, and beautiful birds will be seen with her, three fifties of swans about her, and I will make ready for them.’

‘No matter that,’ said the Dagda, ‘since I know the nature you have brought upon her.’

Peace and friendship were made among Ailill and Ethal and the Dagda then, and the Dagda bade them farewell and went to his house and told the news to his son.

‘Go next Samhain to Loch Bél Dracon,’ he said, ‘and call her to you there.’

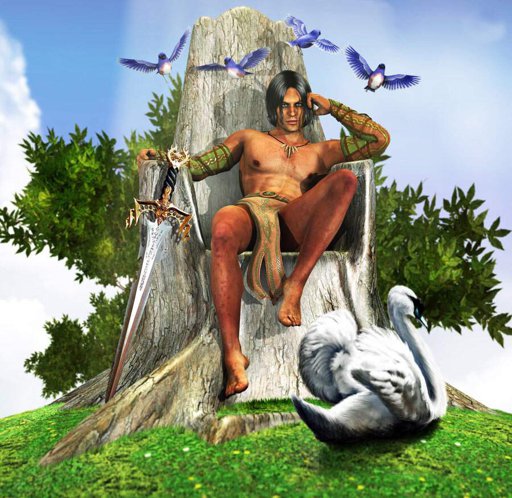

Aengus went to Loch Bél Dracon, and there he saw the three fifties of white birds, with silver chains, and golden hair about their heads. Aengus was in human form at the edge of the lake, and he called to the girl, saying

‘Come and speak with me, Cáer!’

‘Who is calling to me?’ sked Cáer.

‘Aengus is calling,’ he replied.

‘I will come,’ she said, ‘if you promise me that I may return to the water.’

‘I promise that,’ he said. She went to him then and he put his arms round her, and they slept in the form of swans until they had circled the lake three times.

Thus, he kept his promise. They left in the form of two white birds and flew to Brú na Bóinne, and there they sang until the people inside fell asleep for three days and three nights. The girl remained with Aengus forever after that and it is how the great God of love and youth found his own true love forever.