Nestled in the heart of Ireland’s ancient landscape, the Hill of Uisneach stands as a testament to the country’s rich history and cultural heritage. Often referred to as the navel or centre of Ireland, the hill is steeped in mythology, folklore, and historical significance. In this post, we’ll explore the Hill of Uisneach, the historical festival of the fires known as Bealtaine, and the eternal spirit of Ireland that is embodied by its ancient druidic legacy.

A Sacred Meeting Ground: Uisneach as the Meeting Place of the Five Provinces

Located in County Westmeath, the Hill of Uisneach holds great mythical significance in Irish culture, not only as the meeting point of the five ancient provinces but also as the location of numerous legends and stories that form the backbone of Irish mythology. In addition to its geographical significance, the Hill of Uisneach is believed to be a gateway to the Otherworld, a mythical realm inhabited by deities, spirits, and the souls of the dead. This connection to the Otherworld makes the hill a powerful symbol of the eternal spirit of Ireland, and a place where the veil between the worlds is thin.

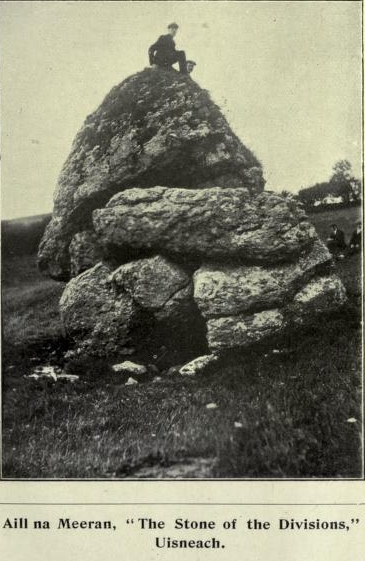

The Stone of Division, also known as Aill na Míreann, is a significant landmark on the Hill of Uisneach in Ireland. According to legend, this ancient limestone boulder was used by the mythical king Eochaid to mark the meeting point of Ireland’s five provinces. The Stone of Division carries immense symbolic importance, representing the unity of Ireland’s regions and the country’s rich cultural heritage.

Crossroads of The Divine and Mankind: Uisneach as a Liminal Space Between Worlds

The hill’s connection to the story of the Milesians and the goddesses Eriu, Banba, and Fola further underscores its importance in the ancient lore of Ireland. According to the legend, the Milesians, led by their chieftains, the sons of Míl Espáine, travelled from Spain to Ireland to claim the island as their own. When the Milesians arrived in Ireland, they encountered the Tuatha Dé Danann, a supernatural race of beings who were the existing inhabitants of the land. The Tuatha Dé Danann had their own pantheon of gods and goddesses, including the three sisters Eriu, Banba, and Fola.

Eriu, Banba, and Fola were powerful goddesses who represented the sovereignty of Ireland. Each goddess was associated with a different aspect of the land and its people. Eriu, from whom the name “Éire” (Ireland) is derived, symbolized the land itself, while Banba represented the spirit of the Irish people. Fola, on the other hand, was the embodiment of prosperity and abundance, ensuring that the land would be fertile and the people would thrive.

As the Milesians sought to claim Ireland, they met the three goddesses who challenged their right to the land. The Milesians, recognizing the power and importance of the goddesses, pledged to honor and respect them in exchange for their blessing and support. The goddesses agreed, and the Milesians named the island after Eriu, as she was the most prominent of the three sisters.

This encounter between the Milesians and the goddesses imbued the Hill of Uisneach with an even greater spiritual significance, marking it as a sacred place where the forces of the Otherworld and the mortal realm intersect.

The hill is also associated with the story of the mythical king Lugh, who is said to have established the Lughnasadh festival (or Telltown Games), a celebration of the harvest that takes place on August 1st.

With a Burning Passion: Uisneach and the Great Festival of Fire at Bealtaine

The Bealtaine festival is a rich and vibrant celebration that has its roots in the ancient Celtic (western-northern European) world. Its origins can be traced back thousands of years, predating the arrival of Christianity in Ireland.

Bealtaine, held on the 1st of May, marked the transition from the dark half of the year to the light half, symbolizing the onset of the warm and bountiful summer season. This period was of great significance to the Celts, as it represented the triumph of light over darkness and the promise of a fertile and prosperous year ahead.

At the core of Bealtaine festivities were various customs and rituals designed to honour the forces of nature, ensuring the protection and well-being of the community.

One of the most enduring traditions of Bealtaine is the lighting of bonfires, which were believed to harness the power of the sun and purify the surrounding environment.

It was common for people to gather around these fires, sharing food and stories, and participating in rituals such as the driving of livestock between two flames to bless and protect them. In addition to these communal activities, individuals would often bring the embers from the bonfires back to their homes, using them to relight their hearths as a symbol of the renewed warmth and light of the season.

Another tradition observed by the early Irish can be still found in the example of “May Bushes,” which involved the decoration of hawthorn trees or branches with flowers, ribbons, and other adornments.

This custom, which likely has its roots in the veneration of sacred trees by the ancient Irish, was eventually associated with the Christian feast of St. John, which takes place on May 1st as well. Despite the many changes and adaptations that have occurred over the centuries, the core themes of renewal, growth, and fertility continue to define the Bealtaine festival, reflecting the timeless connection between the people of old Gaelic Ireland and the natural cycles of the earth.

The Fire of Uisneach as a Beacon of Hope for Gaelic Identity and Tradition?

In recent decades, there has been a welcome and growing interest among the Irish of Ireland and our diaspora in reconnecting with the ancient Gaelic traditions and rituals, leading to the revival of the Bealtaine festival in 2010, having been dormant for several centuries since the collapse of the old Gaelic order.

I was fortunate enough to attend and witness the rekindling of this age-old tradition. And that’s not all, my friends and I were blessed to be invited to take part in the ancient procession. You can read all about that wonderful but also strange experience below.

Reviving traditions from the ancient Bealtaine festival, the event featured theatre, literature, music, poetry, holistic health, arts, traditional crafts, installations, and sustainability. Paddy Dunning of Grouse Lodge recording studios in Rosemount was the festival’s chief organizer. The festival aimed to spark the Irish imagination with a gathering unlike any other, with fires lit on all 32 of the country’s highest peaks. The event promoted eco-tourism and sustainable living, offering a child-friendly and eco-friendly atmosphere. The lineup included international and Irish acts and unique collaborations. Festival of the Fires utilized the expertise of people behind Electric Picnic, Glastonbury, and the Burning Man festival to create a spectacle never-before-seen in modern Ireland. Since then, the festival has grown in popularity, with communities across Ireland and beyond embracing the ancient celebration.

Modern Bealtaine festivities often incorporate elements of both pagan and Christian traditions, reflecting the complex and evolving nature of Irish culture. Contemporary celebrations may include the lighting of bonfires, dancing, music, feasting, and the sharing of folklore and stories. These events provide an opportunity for people to connect with their ancestral roots, honour the land, and celebrate the eternal spirit of Ireland.

Several years after attending the first revival festival, in 2015, I had the profound honour of speaking on the Hill of Uisneach about Brehon Law – the ancient Irish legal system that governed society for centuries. Who knows how long it had been since these laws were honoured on this site?

The opportunity to share this knowledge at such a spiritually significant location was a deeply moving experience, as it demonstrated the deep connection between the past and present, and the continued relevance of ancient wisdom in modern times. The resurgence of the Bealtaine festival is a testament to the enduring allure of Gaelic culture, and the desire to preserve and celebrate the rich heritage that defines the identity of the Irish people.

Pingback: How Ireland Came To Be Named After A Goddess: The Story of the Milesians Arrival at the Hill of Uisneach - The Brehon Academy