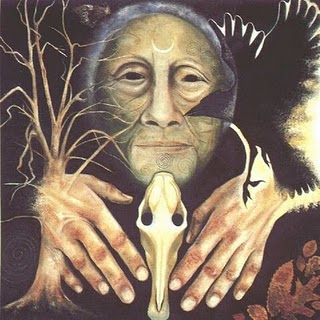

The Cailleach. Her very name translates as ‘Veiled One’, hinting at darkness. Her second name, Bheur or Bheara, translates as ‘shrill’ or ‘sharp’, referring to the cold winter wind she brings in her skirts.

In Ireland, she is known as Cailleach Bearra (the Old Lady of Bearra), on the Isle of Man she is Caillagh ny Gyomagh (the Shrouded Woman of Gloominess), and among several found in Scotland, the Cailleach Bheur or Beira (the Sharp Crone) or Cailleach Mhor Nam Fiadh (the Great Old Woman of the Deer).

Folktale takes this figure’s history back to the beginning of time, but it is only within the last two centuries that most of the material regarding the Cailleach’s history has been documented. The earliest recorded literature of the Cailleach is found in the ninth-century Irish text: ‘The Lament of the Old Woman of Beare.’

Written by an unknown author in the Yellow Book of Lecan, this is the first tale that specifically names the Cailleach as she is known today.

Is mó láu

Translated by Kuno Meyer.

nád muir n-oíted imam-ráu;

testa már mblíadnae dom chruth

dáig fo-rroimled mo chétluth.

Is mó dé

damsa in-diu cen buith té;

gaibthi m’étach cid fri gréin

do-fil aes dom aithgin féin….

Am minecán, mon-úar dam,

cach derc cáin is erchraide,

iar feis fri caindlea sorchai

bíthum dorchae derthaige….

Céinmar insi mora máir,

dosn-ic tuile íarna tráig ;

os mé, ní frescu dom-í

tuile tar ési n-aithbi.

Is súaill mo mennat in-diu

ara taibrinnse aithgniu:

an-í ro boí for tuiliu

a-tá uile for aithbiu.

I had my day with kings

Drinking mead and wine:

To-day I drink whey-water

Among shrivelled old hags.

I see upon my cloak the hair of old age,

My reason has beguiled me:

Grey is the hair that grows through my skin –

’Tis thus! I am an old woman.

The flood-wave

And the second ebb tide –

They have reached me,

I know them well.

The flood wave

Will not reach the silence of my kitchen:

Though many are my company in darkness,

A hand has been laid upon them all.

O happy the isle of the great sea

Which the flood reaches after the ebb!

As for me, I do not expect

Flood after ebb to come to me.

There is scarce a little place today

That I can recognise:

What was on flood

Is all on ebb.

In the folklore of Ireland and Scotland the Cailleach is seen as an embodiment of the cold days. She is commonly known as Beira, Queen of Winter.

Her dominion begins at Samhain, when she could be seen riding through the sky on the back of a wolf.(3) This motif corresponds to the old Gaelic name for the month of January being Faoilleach, Wolf Month.

On stormy nights in early winter, it was said she sang a sorrowful song as she wandered, striking down any signs of green with her ice hammer. Only the holly bush could best her.

Mackenzie’s ‘Wonder Tales’ records a song in the honor of the event:

O life that ebbs like the seal

Donald A. Mackenzie 1917, ‘Wonder Tales from Scottish Myth and Legend

I am weary and old, I am weary and old–

Oh! how can I happy be

All alone in the dark and the cold.

I’m the old Beira again, My mantle no longer is green,

I think of my beauty with pain

And the days when another was queen.

My arms are withered and thin, My hair once golden is grey;

’Tis winter

–my reign doth begin–

Youth’s summer has faded away.

Youth’s summer and autumn have fled–

I am weary and old, I am weary and old.

Every flower must fade and fall dead

When the winds blow cold, when the winds blow cold.

Stories of the deeds the Winter Queen works abound.

On Samhain, she’s said to lock fair Bride in Ben Nevis up in Scotland. Others say the spilling of her creel full of stones is the reason we have Sliabh na Caillighe in Couty Meath, Ireland. The Calleich shepherds the winter storm clouds and lets the ghosts out of the hills to haunt the living on All Hallows’ Eve, and she is the reason all harvest must be brought in by then: whatever is left is a tithe to her, so the tales say, and will poison the mortal who eats of it.

For a creature with such a folk presence, the Calleich is surprisingly difficult to trace back to her roots. Surely humanity has always had an urge to put a human face on events. But this particular manifestation was probably brought to us by a tribe on the Iberian Peninsula first mentioned by Herodotus in his Histories (431-425 BCE), which he called the Kallaikoi in Greek.

The same tribe is documented in Strabo’s Geography (7BCE -23 CE), as well as mentioned by Pliny in his encyclopedia Natural History (77CE), in Latin as Callaeci, a name which Ptolemy has suggested as meaning ‘worshippers of the Cailleach’(9).

It is possible based on this that the Cailleach was known almost two thousand years ago in Spain. Recent linguistic and genetic evidence points to a migration from the Iberian Peninsula to Ireland at the end of the last Ice Age. With this in mind, it is possible that the Callaeci tribe brought the worship of the Cailleach with them when they migrated north, for it is in Ireland that the earliest folktales and place names associated with the Cailleach are found.

At this time of the year, the Calliech stirs again.

The darkness draws in.

Gather ‘round the fire, leave a cup and a loaf out for those who wander.

Tonight is a night for tale-telling.

May you all be warm and well this Samhain night.

By Olivia Wylie.

Resources:

1 – ‘Queen Of Air And Darkness,’ Mara Freeman, https://druidry.org/resources/queen-of-air-and-darkness

2,3,9 – Sorita d’Este & David Rankine 2008, ‘Visions of the Cailleach’, London: Avalonia

4, 5 – Donald A. Mackenzie 1917, ‘Wonder Tales from Scottish Myth and Legend, London: Dover Publications

6 – Proinsias Mac Cana 1970, ‘Celtic Mythology’, New York: Hamlyn

7 – Mara Freeman 2001, ‘Kindling the Celtic Spirit’, San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco

8 – Marian F. McNeill 1959, ‘The Silver Bough: A Calendar of Scottish National Festivals, Candlemas to Harvest Home V.2’

Image art: Night Woman / Crone Tree, Carolyn Hillyer.