The Irish Wolfhound, known in Irish as the Cú Faoil, is a breed of unparalleled size, strength, and historical significance. Renowned as one of the tallest dog breeds in the world, these gentle giants can stand over seven feet (2.15 meters) tall on their hind legs, commanding awe and respect.

With roots stretching back thousands of years, the Irish Wolfhound is woven into the fabric of Ireland’s mythology, history, and culture, serving as a symbol of nobility, ferocity, and loyalty.

A Breed of Nobles and Warriors

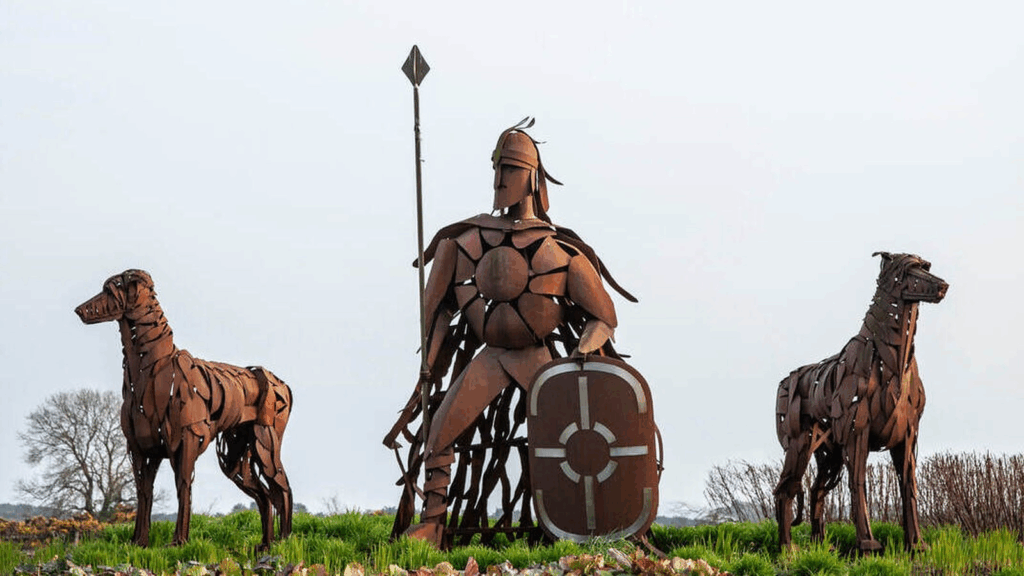

In ancient Ireland, the Irish Wolfhound was a privilege reserved for the elite.

According to Brehon law, only kings, chieftains, nobles, and occasionally poets were permitted to own these magnificent hounds, with poets allowed just two. So valuable were they that their theft could spark battles or even wars.

Adorned with gold and silver collars, they were often presented as lavish gifts to dignitaries, a testament to their prestige (Source: “The Irish Wolfhound: Symbol of Celtic Heritage,” Irish Wolfhound Club of America).

These hounds were multifaceted in their roles, guarding property and livestock from thieves and predators such as wolves.

In times of war, their ferocity was legendary—they were known to drag warriors from chariots or horseback, making them formidable allies on the battlefield.

The legendary war-chief Fionn Mac Cumhaill, leader of the Fianna, reportedly owned over 500 hounds, including 300 battle-ready adults and 200 puppies, who fought alongside his warriors (Source: “Myths and Legends of the Celtic Race,” T.W. Rolleston, 1911).

Legends of the Cú Faoil

Irish mythology is rich with tales of the Wolfhound’s prowess. Fionn’s favourite hound, Conbec, was said to be capable of tracking and retrieving any elk in Ireland for his master’s feasts, even sleeping in the same bed as Fionn—an honour no other hound shared (Source: “The Fionn Saga,” Annals of the Four Masters).

The hounds Bran and Sceolán, born human but transformed into dogs by a fairy’s magic, were celebrated for their courage and striking appearances. Bran was described as “ferocious, white-breasted, sleek-haunched, with fiery deep black eyes,” while Sceolán was “small-headed, with the eyes of a dragon, claws of a wolf, vigour of a lion, and the venom of a serpent” (Source: “The Birth of Bran,” Irish Mythological Cycle).

The Cú Faoil was a versatile hunter, pursuing everything from wild boar to the giant Irish elk and, most notably, wolves. Their speed and strength made them uniquely suited to chase down and kill wolves, earning them their name. Whispers of darker hunts persist in folklore, suggesting they pursued creatures that were neither fully wolf nor man—perhaps a nod to Ireland’s ancient werewolf legends (Source: “Cóir Anmann: The Fitness of Names,” 14th-century Irish manuscript).

Historical Significance

The Irish Wolfhound’s reputation extended beyond Ireland’s shores. In the third century BC, Celtic tribes, accompanied by their great hounds, attacked Delphi, leaving survivors in awe of the dogs’ size and ferocity (Source: “Celtic Myths and Legends,” Peter Berresford Ellis, 1999).

Julius Caesar noted their magnificence in his Gallic Wars, and in the fourth century AD, Roman Consul Symmachus received seven Wolfhounds as a gift, which “all Rome viewed with wonder” (Source: “The Gallic Wars,” Julius Caesar).

The Icelandic Saga of Njal further praises the breed, describing a hound with “a man’s wit” who could discern friend from foe and would “lay down his life” for his master.

The legendary hero Cú Chulainn earned his name—meaning “Hound of Culann”—after slaying a smith’s guard dog and vowing to take its place until a replacement was found. The prefix cú (hound) was a mark of respect, often adopted by kings and heroes to signify their worth (Source: “The Táin,” Thomas Kinsella, 1969).

A Symbol of Irish Heritage

The Irish Wolfhound’s likeness is immortalised in Irish knotwork and decorative art, often depicted with slender heads and lithe bodies in intricate, interlacing patterns.

They adorned the coats of arms of early Irish kings, symbolising their connection to Ireland’s royal lines (Source: “Irish Heraldry,” National Library of Ireland). Their image remains a potent emblem of Celtic heritage.

The Wolfhound and the Wolf

The breed’s name reflects its primary adversary: the wolf.

In ancient Ireland, wolves roamed the dense forests and misty moors in such numbers that the island was sometimes called “Wolfland.”

The town of Coleraine faced a massive wolf attack in 1650, and travellers near Lisburn and Drogheda reported pack assaults around the same time (Source: “Wolves in Ireland,” Kieran Hickey, 2011).

Brehon law mandated wolf hunting to protect livestock, and ring forts were constructed partly to deter their raids.

Wolves also held a complex place in Irish culture. They were considered malevolent, yet their parts were used in early medicine—wolf meat to ward off phantoms and wolf heads under pillows to prevent nightmares (Source: “Irish Folk Medicine,” Patrick Logan, 1972).

By 1786, the last Irish wolf was killed by a pack of Wolfhounds, marking the end of an era (Source: “The Extinction of the Irish Wolf,” Irish Naturalists’ Journal).

Werewolves and the Fianna

Irish folklore hints at darker adversaries for the Wolfhound. The medieval text Cóir Anmann describes Laignech Fáelad, a shapeshifting lord from the Kingdom of Osraí, whose clan could transform into wolves to slaughter rivals.

The 14th-century Book of Ballymote similarly references “the descendants of the wolf” in Osraí, hinting at ancient werewolf cults (Source: “The Book of Ballymote,” Royal Irish Academy).

The Fianna, warrior bands living on society’s fringes, may have donned wolf-skins in rituals, calling themselves luchthonn (wolf-skins) to invoke their ferocity (Source: “The Fianna,” Joseph Falaky Nagy, 1985).

Against such supernatural threats, the Irish Wolfhound was an invaluable protector.

Near Extinction and Revival

As wolves vanished, so too did the need for Wolfhounds, and the breed nearly faced extinction.

By the late 18th century, Oliver Goldsmith lamented that the “great Irish Wolfdog” was “almost worn away” (Source: “A History of the Earth and Animated Nature,” Oliver Goldsmith, 1774).

The revival of the modern Irish Wolfhound owes much to the dedicated efforts of Captain George Augustus Graham in the 19th century, who employed selective breeding techniques to restore the breed from near extinction. Graham meticulously gathered over 300 pedigrees, focusing on dogs with traits closest to the historical Cú Faoil, such as size, strength, and temperament.

To bolster the dwindling population, he crossbred surviving Wolfhounds with related breeds like the Scottish Deerhound, Great Dane, and Borzoi to enhance genetic diversity while preserving the breed’s distinctive characteristics. His approach emphasised health, stature, and the gentle, loyal disposition that defines the modern Wolfhound.

Today, responsible breeders continue these principles, using careful selection and genetic testing to maintain the breed’s vitality and adherence to standards set by organisations like the Irish Wolfhound Club of America (Source: “The Irish Wolfhound,” George Augustus Graham, 1885; Irish Wolfhound Club of America).

These Dogs are Older than History (Video)

If you enjoyed this article and would like to learn more, check out the following video (09:15 mins) that goes into some additional details about the Irish Wolfhound in this extract from ‘The Dogs of Ireland’ by Anna Redlich, along with a poem I found about the Irish Wolfhound.

Modern Mysteries

Even today, the Irish Wolfhound’s mystique endures.

In 2012, hikers in County Fermanagh reported sightings of creatures resembling prehistoric dire wolves—stocky, wide-headed canines with short ears (Source: “Cryptozoology Reports,” Centre for Fortean Zoology, 2012).

While these accounts remain unverified, they fuel speculation about what the Cú Faoil once hunted in Ireland’s shadowy forests.

Conclusion

The Irish Wolfhound is more than a dog—it is a living link to Ireland’s ancient past, embodying the strength, loyalty, and mystique of a bygone era.

From guarding kings to hunting wolves and perhaps even darker creatures, the Cú Faoil remains a towering figure in both history and legend.

Thanks to dedicated breeders, this majestic breed continues to inspire awe, ensuring its legacy endures in the modern world.

Sources:

- Irish Wolfhound Club of America, “The Irish Wolfhound: Symbol of Celtic Heritage.”

- Rolleston, T.W., Myths and Legends of the Celtic Race, 1911.

- Annals of the Four Masters, “The Fionn Saga.”

- Ellis, Peter Berresford, Celtic Myths and Legends, 1999.

- Caesar, Julius, The Gallic Wars.

- The Icelandic Saga of Nial.

- Kinsella, Thomas, The Táin, 1969.

- National Library of Ireland, “Irish Heraldry.”

- Hickey, Kieran, Wolves in Ireland, 2011.

- Logan, Patrick, Irish Folk Medicine, 1972.

- Cóir Anmann: The Fitness of Names, 14th-century manuscript.

- Royal Irish Academy, The Book of Ballymote.

- Nagy, Joseph Falaky, The Fianna, 1985.

- Goldsmith, Oliver, A History of the Earth and Animated Nature, 1774.

- Graham, George Augustus, The Irish Wolfhound, 1885.

- Centre for Fortean Zoology, “Cryptozoology Reports,” 2012.

- Irish Naturalists’ Journal, “The Extinction of the Irish Wolf.”