This article seeks to reconstruct Patrick’s mission within its historical context, assess his strategies for integrating Christian doctrine with Irish culture, consider the legends associated with him, and evaluate his long-term impact on Irish identity.

Saint Patrick, the patron saint of Ireland, is a pivotal figure in the history of Irish Christianity. His successful mission in the fifth century to evangelize the Irish people marks a significant turning point in the religious and cultural landscape of Ireland.

Drawing on hagiographical traditions, archaeological evidence, and historical analysis, it explores how Saint Patrick’s efforts bridged Roman and Gaelic worlds, laying the foundation for Ireland’s emergence as the Island of Saints and Scholars, a center of Christian learning and culture.

A Roman Briton Turned Slave

Patrick’s story begins in Roman Britain, likely in the late 4th or early 5th century, within a Christian family of some standing. His father, Calpurnius, was a deacon, and his grandfather, Potitus, a priest, tying Patrick to the Romano-British Church.

The precise location of his birthplace, which he calls Bannavem Taburniae, remains elusive—scholars suggest areas like western Britain (near modern Cumbria or Wales) or the Severn Estuary.

At sixteen, his life was upended when Irish raiders kidnapped him, transporting him to Ireland as a slave. For six years, he labored as a herdsman, possibly in Antrim or Mayo, enduring harsh conditions.

In his Confession (see below), he describes this period as a spiritual awakening with constant prayer forging his faith.

A dream eventually spurred his escape, directing him to a ship that carried him back to Britain, setting the stage for his later return as a missionary.

The Apostle of Ireland

Saint Patrick (Latin: Patricius; Irish: Pádraig), traditionally dated to circa 385–461 A.D., is celebrated as the Apostle of Ireland.

His mission to convert the pagan Irish to Christianity in the fifth century stands as one of the most successful early Christian missionary endeavors in Europe.

While much of Patrick’s life is shrouded in legend, two surviving documents attributed to him—the Confessio and the Epistola—provide firsthand insight into his motivations, challenges, and achievements.

Patrick’s mission occurred during a period of transition in the late Roman Empire. By the early fifth century, Roman Britain, where Patrick was born, faced increasing instability due to barbarian invasions and the gradual withdrawal of Roman authority.

Patrick’s Confessio recounts his capture at the age of sixteen by Irish raiders, who enslaved him for six years before he escaped and returned to Britain. This experience not only shaped his personal faith but also gave him intimate knowledge of the Irish language, customs, and society—skills that later proved invaluable in his missionary work.

Ireland at this time was a patchwork of tribal kingdoms ruled by chieftains and druids, practitioners of a polytheistic religion tied to nature and oral tradition. Patrick’s mission, traditionally dated to 432 A.D. following his consecration as a bishop, aimed to establish a systematic and widespread Christian presence.

Patrick’s Mission

Patrick’s approach to evangelization was pragmatic and adaptive, reflecting both his theological convictions and his understanding of Irish society. The Confessio reveals a man driven by a sense of divine calling, yet his methods demonstrate a strategic engagement with local power structures and cultural practices.

- Patrick targeted Ireland’s tribal kings and chieftains, recognizing their authority over their people. Conversion of a king often led to the baptism of his followers, amplifying Patrick’s reach.

- Rather than wholly rejecting Irish culture, Patrick incorporated elements of it into Christian practice. The use of the shamrock to explain the Trinity, for example, or similarly, sacred sites like wells and hills were often repurposed as Christian holy places.

- Patrick ordained priests, established monasteries, and organized ecclesiastical communities. These institutions not only spread Christian teachings but also introduced literacy and Roman administrative practices.

Within Ireland, druids and traditionalists opposed the erosion of their influence, and Patrick’s foreign origins occasionally fueled mistrust. His status as a former slave returning as a missionary may have further complicated his reception, though it also underscored his resilience and divine favor in the eyes of his supporters.

Palladius and Patricius: One Man or Two?

A key question in Patrick’s narrative is his connection to Palladius, a missionary sent by Pope Celestine I in 431 A.D. to serve “the Irish believing in Christ.” Palladius’s brief tenure contrasts with Patrick’s more enduring impact, leading to speculation about their identities.

Were they the same person, with “Patricius” (Patrick’s Latin name) as an alias or a title for Palladius? Early medieval sources, like Muirchú’s 7th-century Life of Patrick (Vita sancti Patricii), sometimes blur their roles, but most modern historians argue they were distinct.

Palladius likely ministered to southern Christians before fading from record, while Patrick, arriving later (possibly 432 A.D. or shortly after), targeted the pagan north and west. Patrick’s Confession omits any mention of Palladius, emphasizing his own mission’s uniqueness or perhaps downplaying that of Palladius, which further hints at the two-person theory.

Christians Before Patrick: A Faith Already Rooted

Christianity had made some inroads before Patrick, likely through trade and contact with Roman Britain, but it remained a minority faith. Ireland’s isolation from Rome allowed her to preserve her distinct Gaelic culture.

When he arrived, Ireland already harbored small Christian communities, likely introduced through trade with Roman Britain or Gaul. Figures like Saint Declan of Ardmore, Saint Ciarán of Saighir, and Saint Ailbe of Emly—traditionally dated to the early 5th century—are linked to this pre-Patrician presence, though their stories are tangled in later legend. Declan, for example, is credited with converting parts of Munster, while Ciarán established a monastery at Saighir, and Saint Ailbe established a monastery in Emly, Munster, whose legend tells of his association with a she-wolve who suckled him as a child. There are many parallels with druidic themes, i.e. of nature and being in harmony with the animals and elements.

Palladius’s 431 A.D. mission explicitly targeted these “Irish believing in Christ,” confirming their existence. Patrick’s task potentially was to expand this faith, preaching to both scattered Christians and unconverted pagans, unifying a fragmented religious landscape through his efforts.

“Patricius” as a Title for Patrick?

The idea that “Patricius” (Latin for Patrick) might have been a title rather than his birth name stems from its meaning—“nobleman” or “patrician”—which could suggest an honorific bestowed upon him later in life, perhaps tied to his role as a bishop or missionary.

For example, in the Confessio (paragraph 1), he introduces himself simply as “Patricius, a sinner and son of Calpurnius,” without hinting at an earlier name.

Some scholars speculate that if “Patricius” were a title, his birth name might have been a more common Brythonic (Celtic) name from his native region, such as Máel (meaning “servant” or “bald,” often a prefix in Celtic names) or Succat (sometimes spelled Sucat or Sochet).

Succat appears in later Irish traditions, notably in the 7th-century Life of Saint Patrick, by Muirchú, which claims Patrick’s original name was Succat before he took “Patricius” upon entering the Church. This could align with a practice of adopting Latin names during ordination or missionary work, as seen with other figures like Palladius.

However, Muirchú’s account, written over 200 years after Patrick’s death, blends legend with history, and no contemporary source corroborates Succat. Linguistically, Succat has been linked to Old Welsh or Brythonic roots meaning “war” or “warrior.”

Another theory ties his name to his enslavement: the 9th-century Tripartite Life of Patrick suggests he was called Cothraige (or Qatrikias) by the Irish during his six years as a slave, possibly an Irish approximation of “Patricius” or a separate nickname meaning “fourfold” (linked to serving four households). Yet, this lacks 5th-century evidence and seems more like a retrospective explanation.

Without archaeological finds—like an inscribed object—or a clearer hint in his writings, Patrick’s original name remains lost to history. Some historians lean toward “Patricius” as his birth name, viewing later alternatives as embellishments.

Saint Patrick’s Dream: Ireland Calling

A lesser-explored aspect of Patrick’s life is what transpired between his escape from slavery and his return to Ireland as a missionary.

After reaching Britain, he likely reunited with his family, but his Confession hints at further preparation. He mentions a dream—years after his escape—in which the “voice of the Irish” called him back, suggesting a period of discernment or training.

Scholars speculate he pursued ecclesiastical education, possibly in Britain or Gaul, where monasteries like Lérins or Auxerre were training missionaries. His rudimentary Latin and self-described lack of sophistication imply this education was informal, perhaps guided by local clergy rather than a formal institution.

This interim period, though vague, bridges his transformation from fugitive to bishop, culminating in his ordination and dispatch to Ireland, likely with Church backing.

𝐓𝐡𝐞 𝐋𝐞𝐠𝐞𝐧𝐝 𝐨𝐟 𝐒𝐚𝐢𝐧𝐭 𝐏𝐚𝐭𝐫𝐢𝐜𝐤’𝐬 𝐅𝐢𝐫𝐞 𝐨𝐧 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐇𝐢𝐥𝐥 𝐨𝐟 𝐒𝐥𝐚𝐧𝐞

In the year 432 A.D., Saint Patrick, newly arrived in Ireland as a missionary bishop, sought to make a bold statement and assert the power of the Christian God over the pagan beliefs of the Irish.

His mission coincided with a significant moment in the Irish calendar: the festival of Beltane, a Celtic celebration marking the beginning of summer. This festival was traditionally observed with the lighting of great bonfires, a ritual overseen by the High King of Ireland and his druids, the spiritual and political leaders of the land.

The High King at the time, Lóegaire mac Néill, ruled from Tara, a sacred hill about ten miles south of Slane and the ceremonial center of Irish kingship.

According to custom, the lighting of the Beltane fire at Tara was a royal prerogative, symbolizing the king’s authority and the renewal of the land’s vitality. The druids decreed that no other fire could be lit before the king’s flame blazed, under penalty of death, as this act preserved the sacred order and the primacy of Tara’s ritual.

Patrick chose the eve of Easter—coinciding with Beltane—to challenge the old ways. On the night of March 25, 433 A.D. (or April 20, depending on calendrical interpretations), he ascended the Hill of Slane, a prominent vantage point visible from Tara.

There, in defiance of the druidic edict, he kindled a Paschal fire to celebrate the resurrection of Christ, a symbol of eternal life and the triumph of light over darkness. The flames roared into the night sky, a beacon that could not be ignored.

From Tara, King Lóegaire and his druids saw the unauthorized blaze and were enraged. The druids, skilled in prophecy and ritual, warned the king:

“𝐼𝑓 𝑡ℎ𝑎𝑡 𝑓𝑖𝑟𝑒 𝑖𝑠 𝑛𝑜𝑡 𝑒𝑥𝑡𝑖𝑛𝑔𝑢𝑖𝑠ℎ𝑒𝑑 𝑡𝑜𝑛𝑖𝑔ℎ𝑡, 𝑖𝑡 𝑤𝑖𝑙𝑙 𝑛𝑒𝑣𝑒𝑟 𝑏𝑒 𝑝𝑢𝑡 𝑜𝑢𝑡, 𝑎𝑛𝑑 𝑖𝑡 𝑤𝑖𝑙𝑙 𝑜𝑢𝑡𝑠ℎ𝑖𝑛𝑒 𝑎𝑙𝑙 𝑜𝑢𝑟 𝑓𝑖𝑟𝑒𝑠. 𝑇ℎ𝑒 𝑜𝑛𝑒 𝑤ℎ𝑜 𝑙𝑖𝑡 𝑖𝑡 𝑤𝑖𝑙𝑙 𝑜𝑣𝑒𝑟𝑐𝑜𝑚𝑒 𝑢𝑠 𝑎𝑙𝑙.”

Recognizing the threat to their authority, Lóegaire summoned his warriors and chariots and set out for Slane to confront the audacious stranger. When the king’s retinue arrived, Patrick descended the hill to meet them, unafraid and accompanied by a small band of followers.

Legend holds that as he approached, a miracle occurred: a deer leapt from the woods and stood beside him, a sign of divine protection (some versions claim Patrick himself was briefly transformed into a deer to evade capture). Undaunted, Patrick proclaimed the message of Christ, wielding the power of his faith against the druids’ incantations.

A dramatic confrontation ensued. The druids, led by their chief, challenged Patrick with displays of magic—summoning dark clouds or hurling curses—but Patrick countered each with prayers and signs of the cross, dispelling their sorcery. In some tellings, one druid rose into the air to prove his power, only to fall to his death when Patrick invoked God’s name.

Awed and fearful, the king relented, granting Patrick permission to preach, though Lóegaire himself did not convert. The fire on Slane burned on, a symbol of Christianity’s foothold in Ireland.

From that night, Patrick’s mission gained momentum, as word of his courage and miracles spread across the island. The Hill of Slane became a sacred site, and the event cemented Patrick’s reputation as a fearless apostle who brought the light of a new faith to Ireland.

The fire on Slane represented the triumph of Christianity over paganism, a narrative reinforced by the absence of snakes in Ireland—another legend attributed to Patrick driving out evil.

The Legend of Saint Patrick Banishing the Snakes from Ireland

One of the most enduring legends about Saint Patrick, the fifth-century missionary credited with bringing Christianity to Ireland, is his miraculous expulsion of snakes from the island.

According to the tale, Patrick’s mission to convert the pagan Irish was met with fierce resistance from the druids. These encounters often escalated into dramatic confrontations, testing Patrick’s faith against the powers of the natural and supernatural world.

Saint Patrick standing on a snake in Purgatory,

From Saint Patrick’s Purgatory: England, 1451, Royal MS 17 B XLIII, f. 132v.

The story of the snakes is said to have occurred after Patrick’s bold lighting of the Paschal fire on the Hill of Slane in 433 A.D.

Enraged by Patrick’s growing influence, the druids sought to undermine him, using their mastery of nature to summon serpents—symbols of their power and the ancient spirits of the land—to drive him away. In some versions, the snakes were conjured as a physical threat; in others, they represented the pervasive presence of pagan beliefs.

Undeterred, Patrick ascended a high hill—often identified as Croagh Patrick in County Mayo, a site later associated with his forty-day fast. Armed only with his staff (sometimes called the Bachall Íosa, or Staff of Jesus) and his unshakable faith, he confronted the writhing mass of snakes.

Raising his staff and invoking the power of God, Patrick commanded the serpents to leave Ireland forever. The earth trembled, and the snakes, unable to resist the divine authority channeled through him, slithered away in a frenzied exodus. Some tales claim they fled into the sea, drowning in the waves, while others say they vanished into the earth, never to return.

From that day forward, it is said, Ireland was free of snakes—a distinction that persists in the natural world and has been attributed to Patrick’s miracle. The legend concludes with Patrick standing victorious, his staff planted in the ground as a symbol of Christianity’s triumph, while the druids retreated, their power diminished.

The Shamrock and the Trinity: A Teaching Tool

Another legendary tale about Saint Patrick is his use of the shamrock—a three-leafed clover—to explain the Christian doctrine of the Trinity to the Irish.

According to tradition, while preaching to pagan tribes unfamiliar with the concept of one God in three persons—Father, Son, and Holy Spirit—Patrick plucked a shamrock from the ground, using its single stem and three distinct leaves to illustrate unity and distinction.

Though this story first appears in written records centuries after his death, notably in the 17th-century works of Irish clerics like Thomas Messingham, it reflects Patrick’s known approach of adapting local symbols to convey Christian ideas.

His Confession and Letter to Coroticus do not mention the shamrock, suggesting it may be a later embellishment, but the plant’s abundance in Ireland and its cultural resonance make it a plausible tool for his mission. Scholars see this as an example of his ingenuity, bridging the gap between Irish nature reverence and theological complexity, cementing his image as a teacher attuned to his audience.

When Patrick Defeated Crom Cruach

Crom Cruach was a pagan deity, depicted as a golden idol surrounded by twelve stone figures on the plain of Magh Slecht (‘plain of slaughter’) in modern-day County Cavan. Known as the “Bloody Bent One,” he was feared for demanding human sacrifices, especially firstborn children, in return for prosperity. This dark cult was a significant target for Patrick, Ireland’s missionary bishop, during his 5th-century campaign to spread Christianity.

| According to tradition, he denounced the idol as a demonic falsehood and struck the ground (or the statue itself) with his Bachall Íosa. The earth shook, and the golden idol sank into the ground, banished to the underworld, while the surrounding stones lost their power. |  |

This dramatic act, recounted in texts like the Tripartite Life of Saint Patrick, symbolized the triumph of Christianity over paganism.

The event awed the local people, who reportedly converted to Christianity immediately, abandoning their old rituals. Magh Slecht, once a site of terror, was transformed, with some stories suggesting Patrick built a church nearby to mark the victory.

Though likely embellished over time, the tale underscores the cultural shift from Ireland’s pagan past to its Christian future, with Patrick’s staff serving as a potent symbol of his authority and faith.

The Confession: A Window into Patrick’s Soul

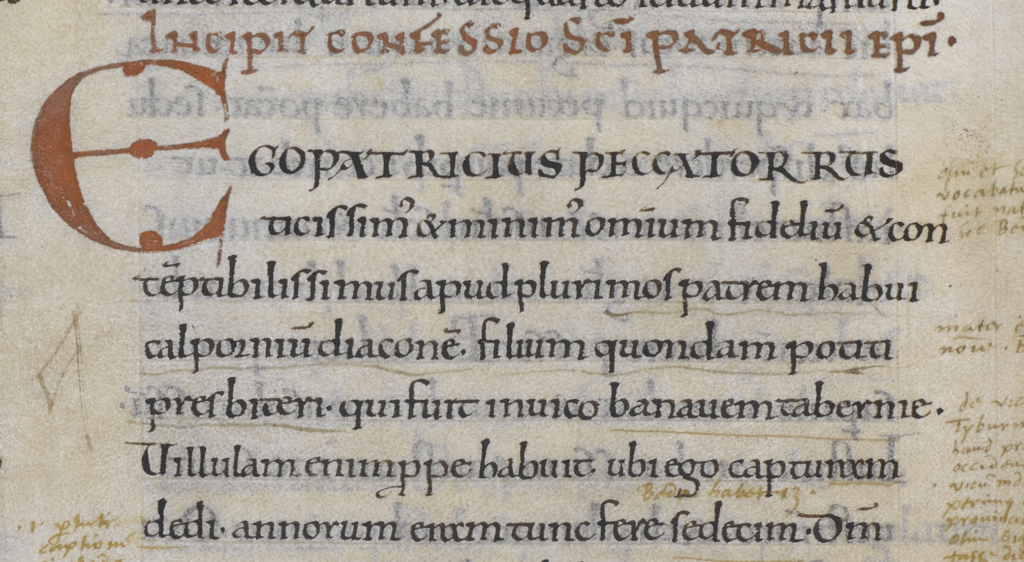

Patrick’s Confession, written in unpolished Latin late in his life, stands as a cornerstone of his historical authenticity. This spiritual autobiography recounts his enslavement, escape, and divine call to evangelize Ireland.

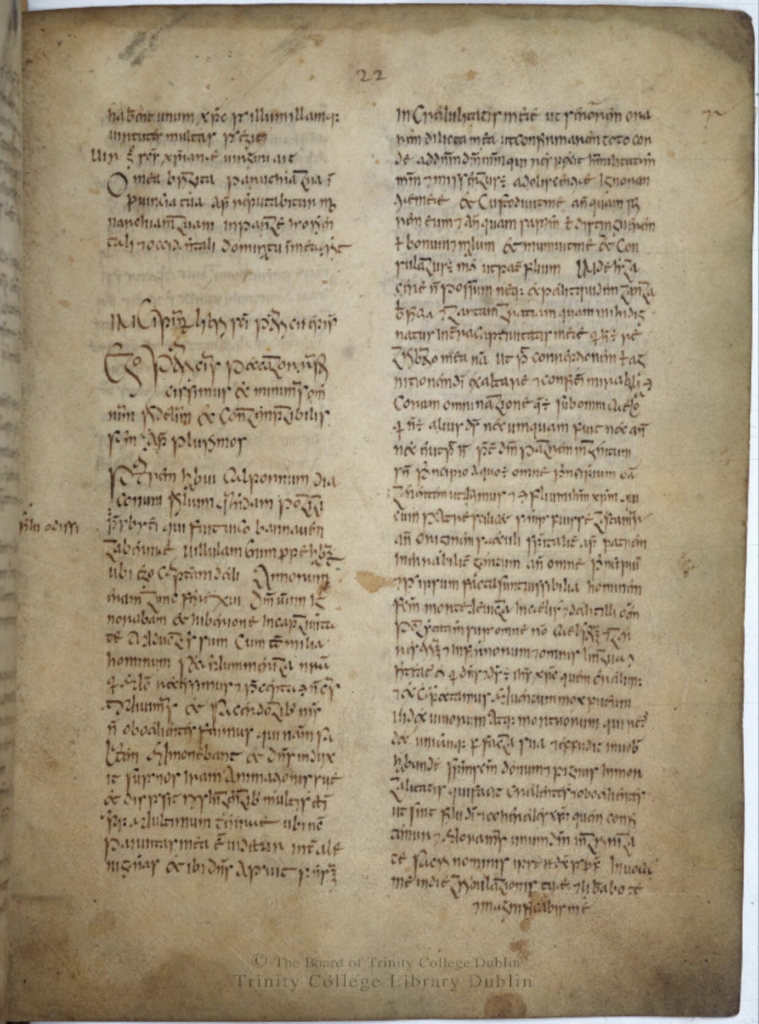

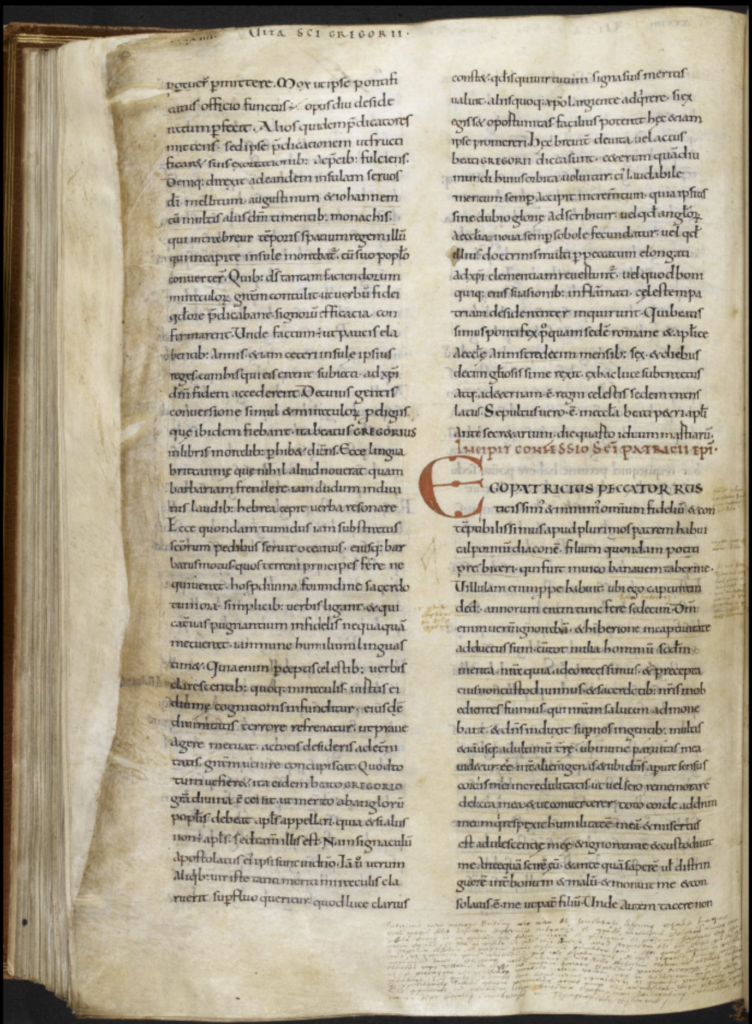

‘My name is Patrick, I am a sinner’: Opening lines of the Confessio, Cotton MS Nero E I/1, f.169v.

Most compelling is his admission of a youthful sin—committed before his abduction—that resurfaced years later when critics within the Church challenged his authority. Though he withholds details, his shame is evident, and he defends himself with humility, claiming God’s forgiveness:

One time I was put to the test by some superiors of mine. They came and put my sins against my hard work as a bishop. This hit me very hard, so much so that it seemed I was about to fall, both here and in eternity. But the Lord in his kindness spared the converts and the strangers for the sake of his name, and strongly supported me when I was so badly treated. I did not slip into sin and disgrace. I pray that God not hold this sin against them. [26]

They brought up against me after thirty years something I had already confessed before I was a deacon. What happened was that, one day when I was feeling anxious and low, with a very dear friend of mine I referred to some things I had done one day – rather, in one hour – when I was young, before I overcame my weakness. I don’t know – God knows – whether I was then fifteen years old at the time, and I did not then believe in the living God, not even when I was a child. In fact, I remained in death and unbelief until I was reproved strongly, and actually brought low by hunger and nakedness daily. [27]

My defence was that I remained on in Ireland, and that not of my own choosing, until I almost perished. However, it was very good for me, since God straightened me out, and he prepared me for what I would be today. I was far different then from what I am now, and I have care for others, and I have enough to do to save them. In those days I did not even have concern for my own welfare. [28]Saint Patrick’s Confessio; paragraphs 26-28, transl. McCarthy.

Scholars view this embarrassing disclosure as a mark of credibility: a fabricated saint would unlikely expose such a flaw.

Saint Patrick’s Confessio – ca. 807 AD Trinity College Dublin Library Ms. 52 Book of Armagh |  Saint Patrick’s Confessio – ca 1000 AD British Library Ms. Cotton Nero E.1 |

The Confession’s rough style—Patrick laments his lack of formal education—further reinforces its genuineness, distinguishing it from later, polished hagiographies.

Patrick’s Letter to Coroticus: A Voice of Justice

Beyond his Confession, Patrick’s Letter to Coroticus (aka The Epistola) offers a vivid glimpse into his character as a shepherd willing to challenge power. Patrick urges repentance in his Epistola, warning of punishment for unrepentant sinners.

It denounced the British chieftain and warlord Coroticus—likely a Christian chieftain— for enslaving Irish Christians, including newly baptized converts and “handmaids (aka virgins) of Christ”, highlighting the external threats Patrick faced from raiders and rival powers:

“Greedy wolves have devoured the flock of the Lord, which was flourishing in Ireland under the very best of care — I just can’t count the number of sons of Scots [in this case presumably Irish Gaels] and daughters of kings who are now monks and handmaids of Christ.”

Patrick’s outrage is palpable: the fiery epistle excommunicates Coroticus and his men, branding them as “rebels against Christ” and demanding the captives’ release:

“So where will Coroticus and his villainous rebels against Christ find themselves — those who divide out defenceless baptised women as prizes, all for the sake of a miserable temporal kingdom, which will pass away in a moment of time. Just as a cloud of smoke is blown away by the wind, that is how deceitful sinners will perish from the face of the Lord. The just, however, will banquet in great constancy with Christ. They will judge nations, and will rule over evil kings for all ages. Amen.”

As a bishop, he defends his flock, yet feels isolated and criticized, which weakens his authority. Far from a detached cleric, he reveals deep pastoral care, mourning the fate of his flock and risking enmity to defend them. This anxiety may drive him to invoke God’s ultimate authority to bolster his words:

“I bear witness before God and his angels that it will be as he made it known to one of my inexperience. These are not my own words which I have put before you in Latin; they are the words of God, and of the apostles and prophets, who have never lied. Anyone who believes will be saved; anyone who does not believe will be condemned — God has spoken.”

Women in Patrick’s Mission: Unsung Allies

Saint Patrick’s writings reveal that women were vital to his mission in Ireland, far beyond passive converts. In his Letter to Coroticus, he condemns the enslavement of “handmaids of Christ”—consecrated women, likely early nuns—who were active in his fledgling Church.

His Confession praises noblewomen who embraced Christianity despite family opposition, some taking vows of chastity. These women, from high-status converts to religious “handmaids,” disrupted Gaelic norms, where women’s roles centered on marriage.

Their influence likely helped Patrick reach elites, with some hosting Christian gatherings or teaching others. The “handmaids,” targeted by Coroticus, suggest a formal role—perhaps as prayer leaders or caregivers—while noblewomen bridged pagan and Christian worlds.

Patrick’s inclusive approach, possibly inspired by Irish traditions of female seers, positioned them as co-laborers, their courage and faith helping to establish Christianity in Ireland.

Archaeological Evidence: Traces of Patrick’s Presence

Efforts to tie Patrick’s story to physical evidence center on sites like Armagh and Saul, yet the archaeological record remains elusive and contested.

Armagh, traditionally linked to Patrick as his ecclesiastical base, boasts early Christian artifacts—such as carved stones and church foundations—dated to the 5th or 6th century, suggesting a religious hub that could align with his mission. The Seats for the Primates of both the Protestant Church of Ireland and the Roman Catholic Church are based here. Each has its own Saint Patrick’s Cathedral across the town from each other, explaining why Armagh also came to be called ‘The Cathedral County’. Armagh also boasts a rich scholastic history thanks to the famous school that once prospered here and, notably, the Book of Armagh, which was composed here in the 9th century.

Saint Patrick’s Roman Catholic Cathedral, Armagh, Ireland. |

Saint Patrick’s Church of Ireland Cathedral, Armagh, Ireland. |

Saul, in County Down, is tied to his death and early ministry, with a nearby hill known as Slieve Patrick hosting a medieval church site.

Legend also states that three artifacts were collected by Colum Cille (aka Columba), who took them from Patrick’s tomb 60 years after his death. These include “The Bell of the Testament,” “Saint Patrick’s Goblet,” and “The Angel’s Gospel,” as relics.

| The National Museum of Ireland holds “The Bell of the Testament,” first noted in 552 in the Annals of Ulster. The iron bell, later bronze-coated, is simple, with a riveted handle. In 1044, it reportedly worked a miracle, sparking a dispute between two kings. It measures 16.5 cm tall and weighs 1.7 kg. |

Described as a valuable item, Saint Patrick’s Goblet was sent to Down (modern Downpatrick) under an angel’s guidance, as noted in the Book of Cuanu. Unlike the bell, no record confirms the goblet’s subsequent fate. It may have been lost, destroyed, or stolen during Viking raids. Some speculate it could still lie buried near Down Cathedral, but no archaeological evidence supports this.

Named for a legend that an angel purportedly handed the gospel to Columba, “The Angel’s Gospel”—possibly a Gospel text linked to Patrick’s ministry—held immense spiritual value. With no surviving artifact identified as this relic. It could have perished in the turmoil of early medieval Ireland, destroyed or stolen during the Viking raids, as it is highly unlikely that it remains undiscovered in a monastic archive. Without concrete evidence, its current location remains unknown.

However, no definitive relics or inscriptions bear Patrick’s name, and the sparse material culture of 5th-century Ireland complicates attribution. Scholars debate whether these sites (Armagh and Saul) reflect Patrick’s direct influence or later veneration by a Church eager to claim him.

His Death and Burial: A Final Anchor

Patrick’s death is traditionally placed on March 17, 461 A.D., at Saul near Downpatrick. By then, his efforts to evangelize pagans and strengthen existing Christians had spread the faith throughout Ireland.

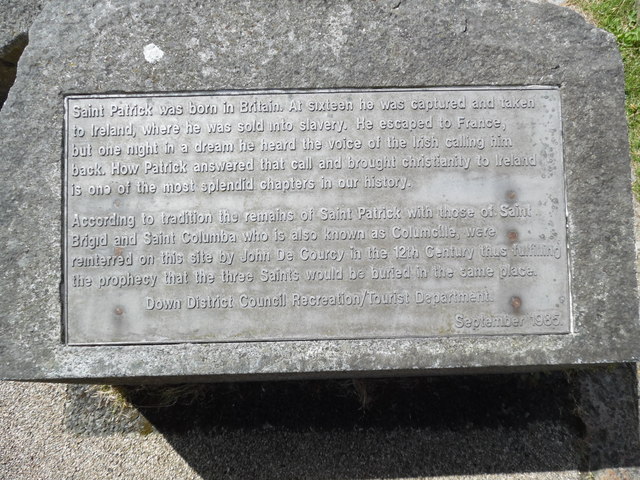

St. Patrick’s Grave at Down Cathedral in Downpatrick, Co. Down, Northern Ireland

His approach—using local symbols like the shamrock and confronting pagan rituals—won converts and rooted Christianity in Irish soil. Monastic communities inspired by his work began to emerge, laying the foundation for Ireland’s later spiritual prominence. Tradition maintains he was buried at Downpatrick, though some annals suggest a later date, around 493 A.D., reflecting ongoing debates about his timeline.

Inscription at St. Patrick’s Grave at Down Cathedral in Downpatrick, Co. Down, Northern Ireland

Cultural Legacy

In the centuries that followed, monastic hubs like Armagh—linked to Patrick as his ecclesiastical seat—along with Clonmacnoise (Saint Ciarán) and Glendalough (Saint Kevin), emerged as beacons of learning, copying manuscripts and preserving knowledge during Europe’s Dark Ages.

This “Golden Age” of Irish saints and scholars, from the 6th to 9th centuries, built directly on Patrick’s work, producing missionaries who were poised to bring the light of Christianity back into Europe upon the fall of the Roman Empire, and produced wonderous illuminated texts like the Book of Kells, the Book of Durrow, the Book of Leinster and many others.

Culturally, Patrick grew into a potent symbol of Irish identity, his legacy solidified after the 12th-century Norman invasions and later English rule heightened the need for a unifying figure.

His feast day, March 17th, known as St. Patrick’s Day, began as a solemn religious observance—once a “dry holiday” in Ireland with pubs closed in reverence—but evolved into a vibrant global celebration of Irish heritage, sparked by early parades in the United States, like the first recorded one in New York in 1762, initially more subdued than today’s festivities.

Bibliography

While this article is a synthetic overview, scholars interested in further study may consult:

- Patrick’s Confessio and Epistola (translations available in various editions).

- Charles-Edwards, T. M. Early Christian Ireland. Cambridge University Press, 2000.

- De Paor, Liam. Saint Patrick’s World. Four Courts Press, 1996.

- Ó Cróinín, Dáibhí. Early Medieval Ireland, 400–1200. Routledge, 2016.

- Dumville, David N., et al. Saint Patrick, A.D. 493–1993. Boydell Press, 1993.

- Hood, A. B. E. (ed. and trans.). St. Patrick: His Writings and Muirchu’s Life. Phillimore, 1978.

- Freeman, Philip. St. Patrick of Ireland: A Biography. Simon & Schuster, 2004.

Pingback: Sheelah's Day: Saint Patrick's Wife, Mother, or a Pagan Goddess? - The Brehon Academy