The Early Irish Brehon Laws relate to the native – and pre-colonial – laws that were extant in Ireland for several hundreds of years. In fact, they are so old we don’t really know when they began, though they started to be written down into manuscripts from the 6th-7th century onwards; after the advent of Christianity which brought a love for the written word in Ireland.

Is ferr fer a chiniud is an old Gaelic saying from the times of the Brehon Laws which can be translated as “a person is not his birth” or, better still, “a man is better than his birth”. It is found quoted in the Uraicceacht Bec, an eighth-century text from Munster which treats the nature of rank and status in early Ireland.

This principle could almost be viewed as a maxim of the Early Irish Law. It is a precept that has been likened to the well-known phrase found in the American Declaration of Independence: “All men are created equal.” Although it meant so much more than that because ‘equality’ did not really exist in early Irish society; a culture that valued rank, merit, and status over treating everyone the same.

Ní comhfhad bhíos barr na mér,

ní bhí uile cách coimhthrén,

clár nocha bí gan bhranán,

ní bhí ál gan uachtarán.Fingers are not the same length,

The 13th century poet Muireadhach Albanach Ó Dálaigh expressed his view of human inequality by artfully stringing together a series of proverbs in his poem “Diambad messe bad rí réil“.

everyone is not equally strong,

every chessboard has a king,

and every litter has a leader.

This was true to such a high degree that its laws are literally teeming with references to the varying grades throughout. All men are created equal in that they are free to succeed or fail on their own merits, and the laws should not be constructed in ways that limit or restrict, or level that ambition.

The Brehon ideal holds that no individual should be hindered or restricted, in any way whatsoever, in his or her personal and individual development merely because of the circumstances of birth.

The individual is, in turn, offered an opportunity and encouraged by the society to achieve what he wills, to make a better life for himself and in so doing raise up his family, his tribe, his community.

A person was judged by their deeds and not their merely their genealogy. And with this gift came a correlory quest as each is charged with the task to improve the conditions of his birth. Thomas Jefferson’s precept, which was inspired by John Locke in his Treatise on Government, simply indicates that every man should have an equal chance to improve such conditions and to deny or prevent him that opportunity was both immoral and unjust.

It mattered not that men were created equal, or even that they should be treated equally, but, on the contrary, that all men should endeavor to use their lives and abilities to become better than the circumstances they were born into, regardless of what those were. That one should have the ambition to raise their rank and status – and, with it, that of their families. To the early Irish, this was both virtuous and noble.

The Brehon precept is in sharp contrast with the beliefs and values of contemporaneous European societies in their view towards status, rights, and the social order. This is evident right down to the post-modern era as expressed through the English proverb “you can’t make a silk purse out of a pig’s ear”. The early Irish did not believe this was true.

“Impossible,” declared the legate. “[…] you cannot stop ideas as long as the Irish Church keeps spreading them. The Irish Church also supports the Celtic heretical practice of allowing anyone to increase his station through effort, while it is truly only God who determines a man’s station, and that is through his birth. The Irish Brehon laws are based on the principle of Is ferr fera chiniud—‘A person is not his birth.’”

Mark Tompkins, The Last Days of Magic (2017)

https://www.romance33.com/romance/3450/3450.html

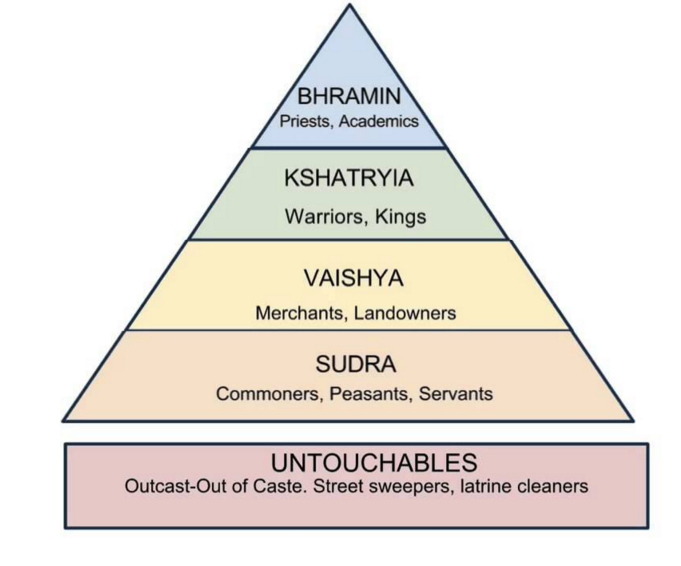

Social Hierarchies: The Hindu Caste vs The Early Irish Social Order

This view can also be starkly contrasted with the caste system of India. While it is claimed that in the earliest of times, the Hindu caste system was not rigidly determined by a person’s birth, but rather their soul quality or nature, this ceased being the case many centuries ago. Before, the caste which someone happened to find themselves in, whether Sudra, Vaishya, Kshatryia, or Bhramin, was determined by the nature of the individual and not the mere circumstances of one’s birth. In times long since past – fuelled not least of all by the higher-caste of Brahmins who, wanting to preserve their power and wealth for their own progeniture, encouraged and facilitated this system in becoming rigidly tied to an individual’s birth. mobility within the caste system (both up and down) is near impossible, culturally frowned upon, and often even violently opposed.

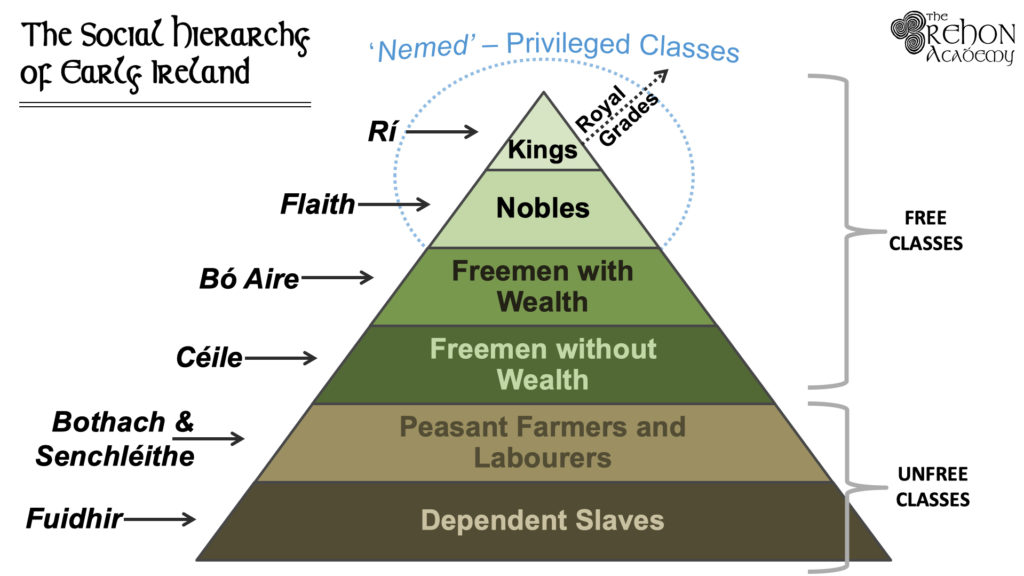

Early Ireland also had a very well-defined and strict social order. Each position was carefully graded into various ranks and sub-ranks. Status and rank were directly tied to one’s ‘honour price’. It was not an egalitarian or even equal society as some would like to believe. Far from it.

We can see this in the nature of chieftaincy and kingship as was practiced in early Ireland, where the leader of a people was selected from among all the eligible candidates in the company, and not merely assigned to the eldest son of the prevailing ruler. In fact, while Ireland had kings and chieftains, the custom of primogeniture as practiced among neighbouring European monarchies was not practiced in early Ireland. There was no divine right to rule. Like everything in life worth having, that privilege had to be earned.

We can also see this in the grades of craftsmen, poets, priests, judges, the people of the arts, even down to comb-makers and horse-keepers. Every profession, whether lay, clergy, common, or noble was divided into its varying grades. In fact, there is not a single profession treated in the laws where these sorts of classifications and distinctions of greatness, ability were not carefully classified according to rank.

However – and this is the beautiful part – this was not fundamentally based on one’s birth. “Once a slave always a slave” was not held to be the case. Granted, it might take some time to raise oneself up to a higher position in society – the general rule being that a position should be held for three generations to truly be established – it was not impossible, nor was it frowned upon. In fact, this precept proves that it was valued, admired, and encouraged.

Duty and Success

Likewise, one could not simply blame his lot in life on the circumstances of their birth. It was up to the individual to climb up and out of their situation anyway, and in so doing raise the status of their entire family and maybe even their whole tuath? Every free land tiller of the tuath was allotted a portion of the common land to put to use. This acted as a sort of safety net, a basic income, or a living wage. Presumably, this would be enough land to eke out minimum sustenance for himself and his dependents, though he never owned that land outright. Occasionally, as circumstances required, as members of the tuath died and younger ones came of age, the land would be re-divided out among the eligible men to put to work. However – and this is the catch – you were not expected to live your life surviving on this bare minimum alone. It was a safety net, and not a million miles from the notion of social welfare today. But it was up to each individual to take this safety net and use their own ambition, brilliance, and enterprise to build a better life from there because is ferr fer a chiniud.

In a free society, people are free to pursue ambition, develop their own competencies and excellence, and can, with a lot of hard work, raise themselves up to a position better than that which they inherited through no fault or choice of their own. They are also free to fail or regress. It was no-one else’s responsibility and so the joy of victory or blame of defeat was placed firmly on one’s own shoulders.

It’s not, therefore, about the cards you are dealt, it’s about the game you determine to play.

You must live in the present, launch yourself on every wave, find your eternity in each moment.

Henry David Thoreau

Fools stand on their island of opportunities and look toward another land.

There is no other land, there is no other life but this.

By: Kevin Flanagan, April 2021.