When we think about ‘fasting for justice’ today many Irish minds of a certain age would likely drift towards thoughts of Bobby Sands and the H-Block Hunger Strikers of 1981. While an important chapter of modern Irish history the principle of fasting for justice or hunger-striking is not a new one; it was practiced by the early Irish in the times of Brehon laws as a means of compelling a stronger party to justice.

Writing in 1894 (almost a century before the H-Block Hunger Strike) Lawrence Ginnel said that:

Distress by way of fasting, now so strange to us because so long obsolete, was clearly designed in the interests of honesty and of the poor as against the mighty.

This form of distress was called troscud, or ‘fasting’. It carried social weight and had legal support as an act of due process. It was a principle which sought to empower a weaker party in compelling a stronger party to comply with justice.

It should be said that the act of troscud in early Irish society was not as extreme as we might first think, as the daily protest most likely only lasted from dawn til dusk for a set period of time. This meant missing the main meals during the day but not all food entirely. The act was symbolic but effective.

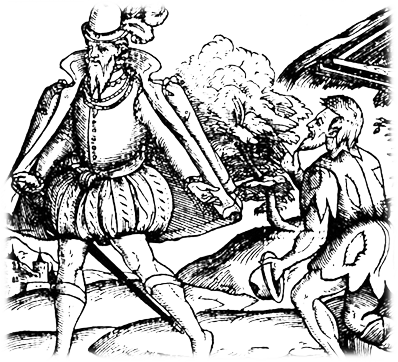

In early Ireland, the higher-classes were called the nemed or ‘privileged’ classes. Members of this class possessed a lot more wealth and power as compared to the lower ‘base-classes’. This made it difficult for members of those lower classes to get justice where they had been wronged by a member of the higher-classes.

Through the course of time a custom developed in Ireland making troscud a requirement, a necessary legal step that had to be first followed before a member of the nemed classes could be brought to court.

The fast took place outside of the home of the defendant, beginning at sunrise and ending at sunset.

This obligation on the weaker party did not hinder them in achieving justice – the primary aim of troscud was to put pressure on the privileged wrong-doer, morally, legally and financially.

Moral condemnation would follow the nemed defendant who dared to eat while someone was conducting the ancient custom of troscud against them, and, if this wasn’t enough, the law held that the initial amount being disputed in the claim would double!

If the nemed defendant still resisted or ignored the call to justice they would themselves lose the protection and benefits of the law.

Troscud could therefore be described as a double-edged sword. On one hand it provided a mechanism for the parties to deal with the matter privately and protect the nemed’s honour; on the other it empowered a weaker party into a much stronger position where:

a) they have the moral support of the community,

b) enhances legal power where the status of an individual would otherwise be too low to compel the wrong-doer,

c) they stand to gain more financially if the offender fails to co-operate; a built-in enforcement mechanism which added incentive for the nemed defendant’s compliance.

Sources:

– Lawrence Ginnell, Brehon Laws A Legal Handbook,

– Fergus Kelly, Early Irish Law.

Pingback: #UnionGirlSummer, History Protests, Ecuador Protects Rainforest, Italy’s Salt Boycott – Nonviolence News