Boycotting refers to a non-violent form of protest or dissent that involves abstaining from engaging with a person, group, or institution, typically in a social or economic sense, in order to express disapproval or force compliance with certain demands, and has been successfully employed throughout history as a tactic to effect social, economic, and political change. Despite its widespread usage in the modern era, the roots of boycotting are not widely known.

The concept of outcasting under Brehon Law was deeply embedded in the early Irish legal and social system. It served as a community-based approach to justice, aiming not only to punish but also to encourage the individual to make amends and reintegrate into the community. Similarly, modern boycotts often seek to bring about change by pressuring individuals, groups, or institutions through social and economic isolation.

On the Origins of the Boycott

The term ‘boycott’ derives from a particular historical figure and event. Captain Charles Boycott, an English land agent in 19th-century Ireland, became the namesake of this now globally recognized term. The story behind this connection provides a fascinating insight into how a local dispute could give rise to a word and concept with international resonance.

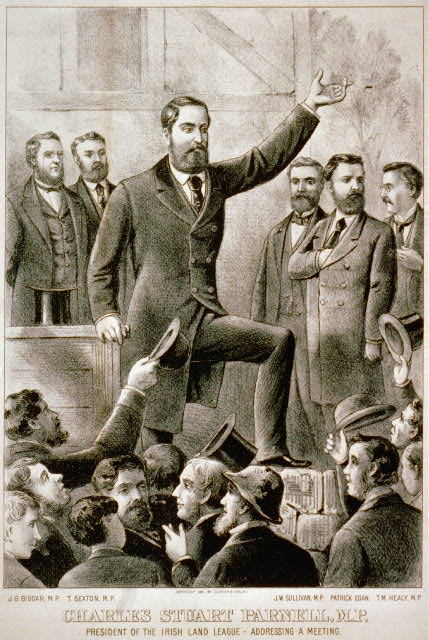

Charles Cunningham Boycott was an English land agent who worked for Lord Erne, a major landowner in County Mayo, Ireland. The Land War was a period of civil unrest in Ireland driven by disputes over land ownership and tenant rights. During this time, Captain Boycott was tasked with enforcing rent collections and evictions, making him a figure of considerable controversy. In 1880, as a response to harsh evictions, local tenants initiated a campaign of social ostracization against Captain Boycott. They refused to work on the land he managed, and local businesses declined to trade with him, effectively isolating him socially and economically. Charles Stewart Parnell would describe this tactic as “putting him in a sort of moral Coventry,” and as an alternative to the gun.

“Now, what are you going to do with a tenant who bids for a farm from which his neighbour has been evicted? Now I think I heard somebody say, “Shoot him”, but I wish to point out to you a very much better way, a more Christian, a more charitable way which will give the lost sinner an opportunity of repenting.

When a man takes a farm from which another has been evicted, you must show him on the roadside when you meet him, you must show him at the shop counter, you must show him in the fair and at the market place and even in the house of worship, by leaving him severely alone, by putting him in a sort of moral Coventry, by isolating him from the rest of his kind as if he were a leper of old, you must show him your detestation of the crime he has committed.”

Charles Steward Parnell, leader of the Irish Party and president of the Land League,

addressing a rally in 1880.

This collective action was so impactful that it caught public attention and gained widespread media coverage. The ‘Boycott’ campaign proved successful, leaving an indelible mark on history. It not only forced Captain Boycott to abandon his position and return to England, but it also gave birth to a new term and concept that came to represent a method of peaceful protest and civil disobedience. Today, the term ‘boycott’ is used globally, in recognition of a form of dissent that began in a small corner of Ireland over a century ago.

The Outcast: The Roots of Boycotting and the Brehon Law

We find much earlier and deeper roots for the origin of boycotting in the cultural and legal practices of early Ireland, long before the term came into use. Known as ‘outcasting’ or ‘ostracization’, these practices were fundamental to the early Irish law system. They served as powerful social tools to maintain harmony, resolve conflicts, and manage aberrant behaviour within communities under the early Irish law system known as Brehon Law. Named after the Brehons or judges who administered it, was the legal system in Ireland before England colonized the island. The laws were a complex system of statutes covering everything from property rights, familial relations, and the resolution of disputes, to the social responsibilities of individuals within the community. They were rooted in the culture, traditions, and social norms of the time, emphasizing restorative justice rather than retributive justice.

Outcasting or ostracisation was not simply a punitive measure but a community-based approach to justice. If an individual consistently broke the laws or behaved in a manner detrimental to the community, they were made an ‘outcast’. This did not mean banishment in a physical sense, but rather social and economic isolation. The community would cease to interact with the person, effectively severing their social and economic ties. The intention was not only to punish but also to compel the individual to make amends and reintegrate into the community.

There are distinct parallels between the ancient Irish practice of outcasting under Brehon Law and the modern concept of boycotts. Both involve a form of social and economic exclusion as a means of enforcing social norms or effecting change. In both practices, the community collectively refrains from engaging with an individual, group, or entity as a form of protest or punishment.

Treatment of the Outcast under the Brehon Laws

One text uses the term “díles” to describe such individuals who have been stripped of their rights due to engaging in criminal or anti-social activities, or refusal to pay a duly owed debt or fine. Another text refers to a criminal whom both the king and the people denounce as a bibdu. Essentially, it signifies a loss of status and that wrongdoers have no legal recourse to laws they have willfully shunned if they happen to become victims of an offence themselves. A thief loses the usual entitlements of sick maintenance and fines for injuries, and their house might be burned without consequences.

Heptad 63 categorizes seven types of individuals as ellidaig or “absconders,” resulting in the forfeiture of their societal rights. These categories include women who abandon their marriages without just cause, individuals who neglect the care of elderly parents, those wielding bloodstained weapons, and absconders from their own kin.

Interestingly, anyone, regardless of high social standing, who harbors an ellidach also forfeits their honour-price. Our sources emphasize that a person is not officially deemed an outlaw until their offence becomes publicized, often at an assembly. According to Tecosca Cormaic, everyone is considered an aurrad or “law-abiding freeman” until they are publicly proclaimed as an outlaw.

Typically, when someone is outlawed, they would leave their own territory and become an exile, known as a deorad, possibly seeking employment as a servant or bodyguard elsewhere. In certain cases, an exile might even establish themselves as a legally recognized aurrad in another territory. For instance, a text states that an exile who purchases land is classified as an aurrad.

Ancient sagas contain references to the banishment, referred to as indarbe, of wrongdoers to foreign lands. In an amended judgment presented in “Togail Bruidne Da Derga,” King Conaire decrees banishment for his foster brothers and other young men who resorted to brigandage, known as “díberg.”

- Díles: Rights or legal entitlements which can be lost due to offences.

- Ellidaig: An absconder or fugitive.

- Ellidach: Another term for an absconder or fugitive.

- Aurrad: A law-abiding freeman.

- Bibdu: A criminal in Old Irish law.

- Deorad: An exile or outcast.

- Indarbe: Banishment, typically as a form of punishment.

- Díberg: Brigandage or outlawry.

- Indarbae co cenn rechtgi: Banishment until the end of the law, implying lifelong banishment.

- Bithchdin: Perpetual law, refers to a law that is ongoing or unending.

- Deorad De: Exile of God, used to refer to a holy man who becomes a hermit.

Differences Between Modern Boycotting and Ancient Outcasting

Despite these similarities, it’s important to note that the term ‘boycott’ was not directly derived from Brehon Law, but rather emerged in the late 19th century during the Irish Land War. However, the communal spirit and the idea of collective action for justice, central to both outcasting and boycotting, can be seen as a recurring theme in Irish history.

While modern boycotts and ancient outcasting both hinge on a form of social and economic exclusion, their purposes and methods often differ. The objective of a boycott is typically to bring about a change in policies or actions, often on a large scale and frequently within a political or economic context. Outcasting under Brehon Law, on the other hand, was more focused on individual behaviour and local community dynamics. Despite these differences, the underlying principle of using social pressure to effect change remains consistent between the two practices

However, it’s essential to note that the connection between outcasting under Brehon Law and the modern concept of boycott is one of thematic similarity rather than direct lineage. The modern practice of boycotting has been influenced by a multitude of historical, cultural, and social factors beyond the tradition of outcasting in ancient Ireland. The parallel between the two is an interesting aspect of the cultural history of Ireland and provides a rich context for understanding the origins of a widely used tool for peaceful protest and social change.

Sources: Fergus Kelly, Guide to Early Irish Law.