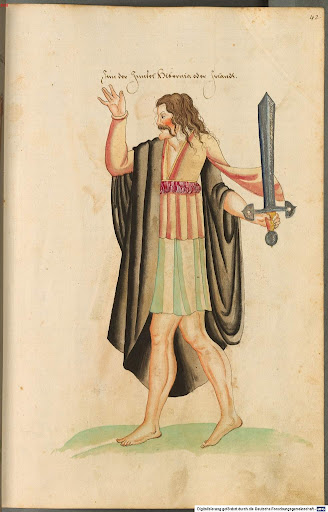

A peculiarity we find in many late medieval and early modern depictions of Gaelic warriors are their swords, which often seem to be “flared” or widened towards the end, a unique design found almost nowhere else.

These images raise eyebrows and questions, with people often wondering whether these weapons were entirely fictional, despite artists usually managing to capture the rest of their subjects as accurately as could be expected.

Doubts are further compounded by the way that no such swords from the periods in question have ever been found. Except that’s not exactly true, as we shall discover!

To lay the archaeological objections to rest, we have found very few weapons or iron artefacts at all from the entire Iron Age to the early modern period.

This is nothing to worry about.

We know from images and accounts of the time, for example, that tens of thousands (at least) of skean long knives must have been manufactured and used down through the centuries.

And yet we’ve found less than a dozen skeans or items that could be identified as having once been skeans!

This is probably the result of Ireland’s damp climate and the easily corroded nature of the metal.

By comparison, we’ve found hundreds of Bronze Age Irish swords, despite their far greater age, because bronze doesn’t corrode as easily.

This holds true across Europe – very few Iron Age helmets have been recovered, although most warriors in that warlike age probably owned one.

So why would Irish swords have such an odd shape to begin with?

I believe there are a few answers to that question – first and probably most importantly, Ireland is a place with tremendous cultural inertia.

We have retained enormous amounts of truly ancient mythology, legends, stories and mythohistories where many, if not most, other cultures have lost theirs.

Following on from that, we can’t help but notice that Bronze Age leaf-bladed swords were fairly blade-heavy since bronze tends to bend fairly easily.

It also goes blunt relatively easily, so you want your sword to become a good bludgeon if that happens. They would probably have been used primarily with slashing cuts for these reasons.

Moving into the Iron Age, this fighting style might not have changed much, so Irish warriors could well have preferred similarly blade-heavy weapons, which would explain the diamond-shaped profile of the swords and, importantly, the famous ring pommel swords.

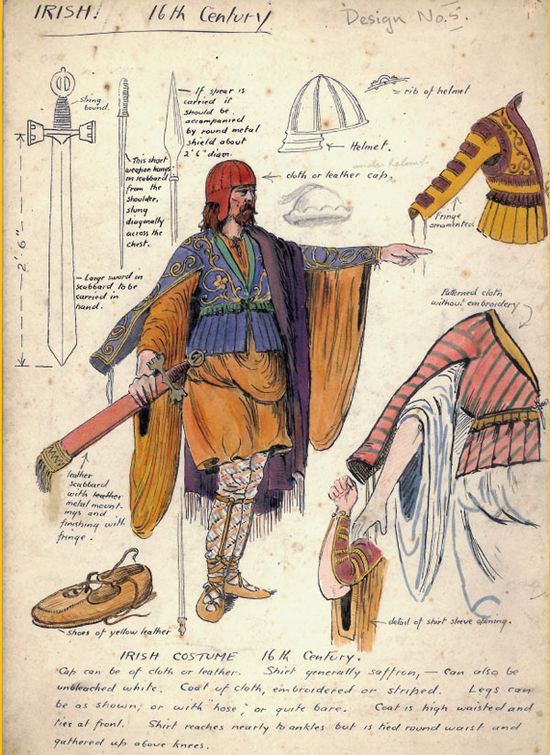

The use of Irish weapons in wide slashing cuts was also noted and recorded by English invaders throughout the early modern period, often with disdain, despite the English suffering more defeats in Ireland than anywhere else.

All very well and conjectural so far, you say, but other than some accounts of battles and some old drawings, do you have any evidence for this progression from Bronze Aged leaf-blade swords (used with wide slashing cuts) -> medieval and early modern iron and steel weapons with diamond shaped profiles (used with wide slashing cuts)?

Yes, we do.

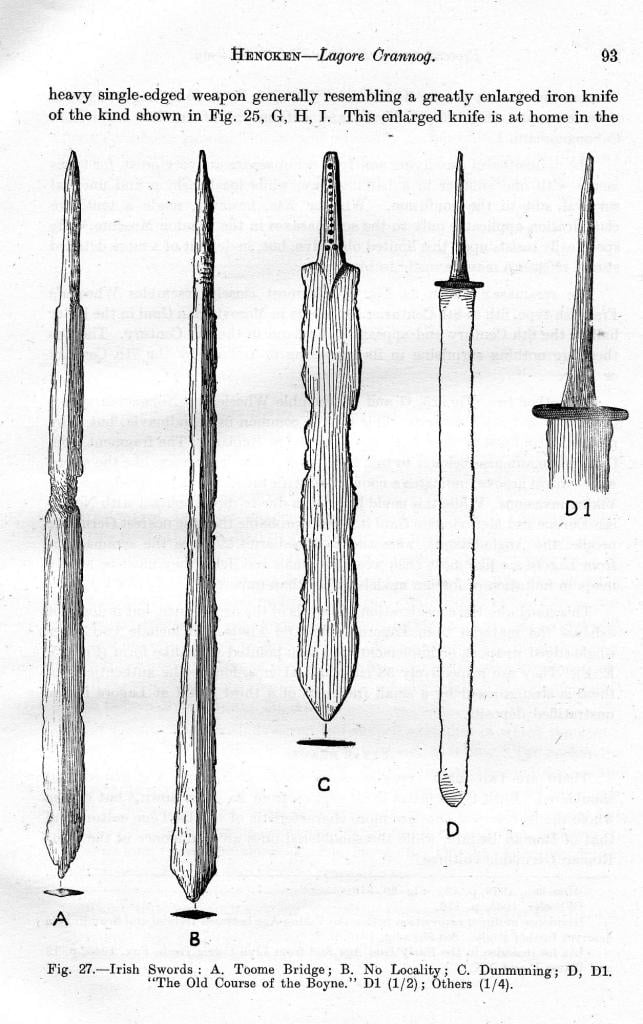

We have, in fact, discovered Irish Iron Age swords with the exact profile shown in 15th and 16th century artwork, dating from…the second or third century AD, when Rome still ruled Britain!

Three of the four blades shown below conform to the blade-heavy diamond profile sword shapes that we see in art almost a millennium and a half later. Even the wider blade shown is slightly flared towards the end.

It might seem shocking to imagine a continuous martial tradition unfolding from the ancient and mysterious Bronze Age right through the rise and fall of civilisations and thousands of years, surviving well into the early modern period, but there seems to be evidence suggesting that’s exactly what happened.

And if it was going to happen anywhere, it would happen in Ireland, keeping in mind that researchers have recently dated the Irish language itself back to the Bronze Age.

As to how these blades were used, an excellent article from the Wilde Irish group offering new insights into the use of the Irish ring pommel sword can be found below, with selected extracts presented here:

“The third rank comprises others, also foot soldiers, who are light-armed swordsmen [Machairaphoroi: i.e., a type of ancient Seleucid light foot, unarmoured, fighting with sword, shield, and spear]. The Irish call them Kerns [Karni].

They whirl spears, which are fitted with thongs, so manfully by strength of muscle that the spears seem to be forced into an orbital circuit like a ring.

They are armoured with shields [Caetra—i.e, the circular wooden buckler, leather-covered, of the ancient Celtiberians] or an iron gauntlet; going into battle, they wear no heavy armour.

With spearpoint, they inflict wounds from afar on horseman and horse; then at close quarters, they enter the fray with drawn swords.

They are notable stone-throwers, but they have no knowledge of how to use their weapons in a well-trained manner: they have no familiarity with the art of the fencing schools, rarely piercing the foe with a thrust, more often wounding him by slashing.

They have an amazing love for their swords, which are kept sharp and not pitted; they care for them diligently so that they may not become rusty or blunt.

The story is told that a man of this class, returning from battle having received four or more dangerous wounds, inspected his sword: when he saw that it was nowhere chipped or bent, he gave great thanks to God that the wounds were inflicted on his body, not on his sword.”

“The functionality of the ring pommel is now more apparent. Deliberately light in weight, it contributes to the blade’s heaviness whilst being wide enough to perform its primary function of preventing the user’s hand from slipping from the grip when in use.

Armour for the non-sword arm would form a primary defense against an attack with such a weapon leaving the sword arm free for retaliation.” “after trying both edges with his thumb, he carefully strops the blade to and fro on his shield until a satisfactory proof of the edge is made by shaving the hair off his arm.”

Baker held that “such a weapon possesses immense power, as the edge is nearly as sharp as a razor. . . one good cut delivered by a powerful arm would sever a man at the waist like a carrot.”

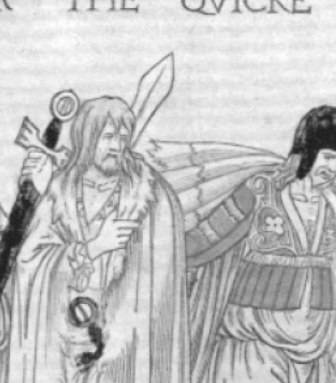

“Christopher Scott Thompson in particular has considered the woodcut ‘Dravne After the Qvicke,’ and feels the kern with drawn ring pommel sword depicts the basic guard stance for this weapon: left foot forward with the sword held back behind the head, blade angled forward, its striking edge held away from the opponent.

His left hand is held up besides his cheek, per the advice of 18th century practitioners like McBane and Lonnergan, who advise this stance when cutting or defending on the inside.

This seems to indicate the ‘equilibrio’ style of swordplay advocated, for instance, by Page in his brief treatise on the eighteenth century Highland broadsword.”

The reader is also invited to consider how this sword-fighting style might have translated to stick fighting after the Penal Laws were enacted, barring the Irish from owning weapons.

By: Emerald Isle Team, 2025.

Sources

Irish Ring Pommel Sword: New Insight into Use, Updated: Oct 31, 2022,

https://www.wildeirishe.com/post/irish-ring-pommel-sword-new-insight-into-use accessed 25th May 2025.