In living memory alone, many countries have experienced drastic changes to its cultural and political constituents, going through a state of transition from one form of government, laws, and ideology to another.

Consider the collapses of the former USSR or Yugoslavia, or the creation of the European Union, for example. During these shifts, the people and the national identity goes through significant change from one state to another, and we call this process transition.

Changes within social and political institutions are merely external manifestations of what at first were internal ideas, concepts, and agreements in the minds of the individuals themselves.

This means that the transition of political institutions from one form to another depends upon the overall ‘acceptability’, the will for change that comes from the hopes and wishes of the public at large.

Transition involves a mental act before it takes shape on the physical sphere. The Overton Window refers to a range of ideas that people will accept from within a huge spectrum from one extreme to another.

This thinking suggests that the phrase “politics is downstream from culture” rings true. But how does one use culture to influence politics?

During the infant years of the Irish Free State, a clash of cultural ideologies took place in the upper echelons of power which would define modern Irish identity for years to come.

In the 19th C., Ireland, also went through a significant period of transition from being under the control of the Westminster government of Britain to being a post-colonial ‘Free State’.

However, and what is most interesting is that Irish institutions hardly changed in form to something new.

Rather, the pre-existing “British model” institutions, that of a bicameral parliament with representative democracy along with a British-style common law legal system, the Kings Inn and Bar Council, and the British style court system were retained upon the establishment of the Irish Free State in 1922.

Irish Four Courts, Dublin.

While, in the end, this meant that Ireland would eventually make its own laws and develop its own legal precedents, the style and procedure of the institutions remained very much the same.

With this said, I will discuss the role of heritage and culture in creating a new national identity during Ireland’s transition from a pre-colonial to a post-colonial independent “Free State” by focusing on the efforts to revive the Áenach Tailteann, or Tailteann Games, between the periods of 1922-1936 – a period I describe as “Ireland’s identity crisis”.

I propose to discuss this particular topic for two principal reasons:

First of all, the Irish experience of transition from centuries of colonialism to developing a new national image as “free and independent” is an interesting case partly because the institutional framework of the state remained much the same. In Ireland, the challenge of transition took another form which involved defining Irish identity, heritage, and culture as being something separate and distinct from Britain. It was about reflecting a vision of Ireland on to the world stage that essentially said ‘we are here, this is who we are, and we are different and unique from Britain’.

Secondly, the example of the Áenach Tailteann, or Tailteann Games, provides insights into the struggle to define what Irish identity would mean within the halls of both political and clerical power, and this struggle can help us to understand the course of Irish history since the founding of the Free State.

Few people know about the efforts to revive ancient Gaelic culture and to connect Irish people with their native identity, independent to that of both Britain and Rome.

We reach a fork in the road where Ireland would either cling more to its Catholic identity or to its earlier Gaelic identity; and this is a fascinating realisation.

The Áenach Tailteann was a festival for sports, arts, and culture which went through several attempts at revival in the infant years of the Irish Free State.

According to Irish mythological accounts, this festival was originally instituted in ancient times by the Gaelic god Lúgh which he began in honour of his beloved foster-mother, the goddess Tailtiu.

The first games were allegedly held around 1600 BC and took place close to the ancient seat of royal power, the Hill of Tara in County Meath, in an area named after Tailtiu and which is still today referred to in its anglicised form of Teltown (located between Oristown and Donaghpatrick Kells).

The Áenach Tailteann is commonly described as ‘the Irish Olympics’, however, they predate the Greek olympic games by around one-thousand years! They lasted until 1169 AD, with the coming of the Anglo-Norman invasion marking the beginning of the erosion of native Irish culture. It would take more than seven centuries for them to be revived again.

Ireland was wholly ruled by the British from their Parliament in Westminster from the 17th C. onwards, although the campaigns of the British – previously the Anglo-Normans – had been ravaging the land for centuries before this and the British establishment had strongholds in the “Irish Pale”, an area including Dublin, Kilkenny, and other surrounding areas of Leinster, from the 12th C. onwards.

The traditional laws and institutions of the native Irish, what scholars today refer to as the brehon law, had always been a threat to the legitimacy of the English monarch’s laws and courts in Ireland.

In 1367, King John issued a piece of legislation titled the Statutes of Kilkenny aimed at the Anglo-Norman lords who had been settled in Ireland now for some generations but who had begun adopting the native Irish customs of law and justice and who – it was proclaimed – would be treated as a traitor should they ever speak the Irish tongue, wear the Irish dress, or seek justice from the Irish brehon courts.

This customary, Gaelic, and native system of law was in use for 1000s of years prior to the Anglo invasions. It remained a deeply embedded aspect of Irish cultural identity up and until the total conquest of Ireland in the 17th century.

The Flight of the Irish Earls in 1607 was an event marking the final conquest of Ireland and heavy planting of Protestant settlers began, notably in Counties Laois and Offaly and later in the northern province of Ulster.

With the implementation of the punitive anti-Catholic penal laws by the British administration, English dominance was firmly established across the island.

By the time of the successful struggle for Irish independence came around, in 1922, Ireland’s native institutions had been thoroughly replaced with British ones and this had been the case for the previous 300 years, and even longer in Dublin itself.

These British institutions had become so well established as part of Irish society that to devolve them and revert to some form of traditional Gaelic law was totally impractical and almost impossible to achieve.

People no longer had knowledge of the old customs, at least not to the extent that could facilitate a revival.

Unsurprisingly, the founding statesmen of the new Irish Free State did not pursue this path, opting instead to retain what had by now become the familiar British model.

Rather than destroying the now well established foundations of the state, the institutions of the state would simply take on an Irish flavour.

The question, then, is what does an Irish style of British government actually look like and can it rightly be described Irish at all, especially when we are well aware of the truly native institutions like the Brehon law?

In those early days of Independence the challenge became one of finding a new image of Ireland, an identity that everyone could support and one that was reflective of the varying communities and classes of the whole island.

Briefly, and for example, we see an attempt at this Irishification of British institutions in the naming adopted for parliament and some of its chief government officers.

The parliament would not be called the House of Commons, rather, it would be call an Dáil, an old Irish world for an official gathering and which occurred periodically throughout the year as an opportunity for clans to come together and discuss important affairs.

Rather than having a Prime Minister, the Irish would call their first officer an Taoiseach, loosely meaning ‘a chieftain’, and the office of Deputy Prime Minister would be called an Táiniste.

This word ‘táiniste’ refers back to the old Gaelic custom of appointed succession. Leaders were not chosen through primogeniture in Ireland, rather they were elected among a number of eligible males (these being called the ríg domhna – meaning, of ‘kingly material’). A tanist (táiniste) was ‘the second’ chieftain and they were selected and named during the reign of the current chieftain while he was still alive.

Additionally, Gaelic was made the official and first language of the state and all official affairs, parliamentary meetings, court proceedings, official publications, would be made available in Gaelic, and all street-signs would include Gaelic versions of place-names.

The preceding paragraphs provide but a few examples of the efforts to give the new Irish state some semblance of Irishness and of having a separate and distinct identity from that of the United Kingdom, but fundamentally, the institutions remained British in nature if not in name.

In any case, the early 20th C. marked a beginning of new dawn for Ireland.

In 1922, six years on from the armed Uprising of 1916, three years on from the War of Independence, and for the first time in centuries, the Irish won the freedom to manage their state independent of British interference; though it would remain under the domain of the United Kingdom.

Tragically, however, Ireland’s six northern counties of Ulster would remain under the control of the British administration.

The movement for Irish independence in this era was partly fuelled by the idea that Ireland always was, and still is, at least culturally, independent from Britain.

We can take note here of the significant role of the Gaelic Athletics Association (GAA) in reviving traditional Irish sports, Conradh na Gaeilge in reviving respect and proliferation of the Irish language and culture, and other similar groups and organisations who were working to revive a sense of Irish identity among the Irish people.

Once the Free State was established, there was felt a need among political circles for Ireland to demonstrate and assert its independent identity. Now that the right of Irish self-determination had been achieved, it was Ireland’s time to express itself and present itself to the world as a new state but one with an ancient identity.

Enter J.J. Walsh, a man who was involved in Ireland’s march forward throughout the previous years of rebellion and war and who remained a guiding force in these early days of the emerging Free State.

J.J Walsh was a visionary and a patriot who understood that independence meant nothing if it did not come with the right of Ireland, and the Irish, to possess, express, and honour their cultural identity.

Less than one year after Ireland had ended its bitter civil war, Walsh successfully managed to revive a form of those ancient Telltown Games that had once been instituted by the great Gaelic god Lúgh, the Áenach Tailteann was back.

By drawing upon symbolic images from Ireland’s heritage not just in terms of the festival itself, but also the through the image of the goddess Tailtiu; herself a symbol of the sovereignty of Ireland, and by reviving these in the heart of the capital of the newly found state, Walsh wanted to demonstrate that Ireland was not just newly founded but actually it had an ancient lineage that predated that of Britain and, in fact, many European nations.

That Ireland’s traditions and heritage were enough to show that, though forcibly suppressed for a time, Ireland had always been its own cultural entity.

In doing so, Walsh sought to use Gaelic heritage and culture to unite the Irish race and believed a revival – or, at least, a grand spectacle – was critical to cementing the idea of a new Irish national identity, both for the Irish themselves and on the international stage.

In a speech on the Áenach, Walsh explained that despite Ireland being a newly formed state, Irish identity was not a newly formed thing but in fact had

A culture as ancient and glorious as Greece or Rome.

To Walsh, the Áenach would be much more than just a sporting event.

It would be an example of a new nation defining itself to the world, an exercise in confidence-building and collective morale-boosting, or, most importantly, a part of the fundamental process of political and institutional transition.

This was a need brought about by the unique circumstances of Ireland’s period of transition. Walsh was perceptive enough to realise the power and even the need for ritual and symbolism in creating a new collective Irish identity.

The Áenach would be restaged as proof positive that Ireland was alive and intact despite the hard decades and centuries it had struggled through previously. That it had become stable and peaceful, and it was believed that the international perception of Ireland would be changed as a result of this.

The first in a series of Áenach Tailteann took place in 1924, the same year as the Paris Olympics, and it was an ambitious affair.

On a state level, basic services were primed for the expected influx of visitors – public transport was adjusted to accommodate the events. In the private sphere, hotels and restaurants prepared to accommodate the extra capacity.

Walsh used the Paris Olympic Games to his advantage, however, by holding the Áenach some weeks afterwards and inviting top athletes to compete in Ireland before travelling home from the Paris games.

The opening ceremony was a grand display and Irish from around the world returned to land of their forefathers as representatives of the countries to which their families had previously emigrated, settled in, and now called home.

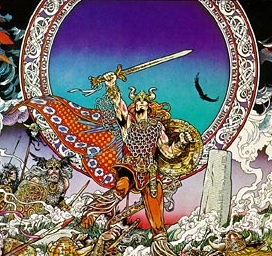

A pageant of costumed Irish warriors, druid priests and priestesses, complete with a representation of the goddess Tailtiu herself, served as a reminder of the games antiquity and a reminder to the Irish of the antiquity of their own cultural identity.

The “games” were in fact much more than just sports. In total, there were 5,000 contenders competing for 1,000 medals.

In addition to shooting, swimming, boxing, rowing, and athletics, there were tournaments in chess, billiards, yachting, poetry, Irish dancing, and even traditional story-telling.

The variety of tournaments was mocked by satirical papers and by the famed Irish poet W.B. Yeats, but on the other hand, the vast choice of games demonstrate Walsh’s intention to have an event that was inclusive of all spheres of Irish society.

Despite some criticisms, the event was generally hailed as a huge success. The Irish Times Newspaper described is the “most important psychological moment in the history of the Free State” and “a tremendous impetus for Ireland”.

Walsh’s plan had been successful, but he felt it was important to repeat this celebration of united Irish cultural identity every four years and continued with the project.

The second Áenach went ahead in 1928 much as the first had, by now the country was more stable than before but the economy was stagnant, industry was slow to develop, and the people remained poor.

In an effort to avoid impending bankruptcy, central planners within the then Fianna Fáil government began searching for ways to recover finances. Having cut pensions by one shilling, they then sought to recover the £20,000 provided for the previous Áenach from Walsh and his committee claiming that the funds provided for the event were a loan.

Walsh drove ahead with plans for the next game regardless but when the government imposed a £3,000 “entertainment tax” on the event it drove him to retire from politics entirely in 1924 criticising what he called the “pro-imperialist” policies of the cabinet.

Without state backing, the Áenach could not claim to be an official state event, but this did not stop Walsh and the games went ahead.

As a statesman and politician in Ireland’s early state, one would think that the loss of the state’s sanction for the Áenach would be enough to deter Walsh, but he goes ahead with his plans anyway.

His actions suggest that his goal of uniting Irish identity went beyond even that of politics, the state, and the government and that he was driven by a higher sense of purpose and meaning.

This was not a game to Walsh. It was a crucial performance like that of a social ritual or cultural baptism for the early Free State, one that would cement its Gaelic identity.

In any case, being the man that he was, having left his career in politics, Walsh later went on to become one of the country’s most successful entrepreneurs.

It was during the third Áenach that we learn of a cultural schism going on behind the scenes in the halls of power. A deep ideological conflict that had been present all along but was not always obvious on the surface.

In July 1932, the Áenach would coincide with the Eucharistic Congress of the Catholic Church. The Eucharistic Congress sought to promote devotion to the blessed sacrament and attracted crowds of over one million people to Dublin’s walled Phoenix Park.

The Áenach opened two days later, and with crowds of only 30,000 paled in comparison. This glaring discrepancy marked a shift in the battle for Irish identity and was a symptom of Eamonn De Valera’s heavily pro-Catholic Fianna Fáil government.

By hosting the Eucharistic Congress, the new state’s largest ever public gathering, De Valera rendered Walsh’s past efforts irrelevant.

To hammer the point, the Áenach was officially opened by Cardinal McRory, Primate of Ireland, accompanied by De Valera, while Walsh was nowhere to be seen.

Ultimately, the Áenach, with its pagan undertones, did not fit with De Valera’s image of a good Catholic Ireland and he was ready to help put an end to the Áenach.

De Valera’s chance arrived during the planning stages for the following Áenach. Since the 1932 event had been such a failure, Walsh decided to come back to work on the committee and began lobbying the state for funds.

Not confident that he could rely on the government for support, Walsh prepared to launch a public campaign but De Valera pre-empted this move by establishing a governmental body to assess the proposal to hold another event.

Not surprisingly, the “Interdepartmental Committee on the Feasibility of Organising the Áenach Tailteann” reported that it was not viable or fit to continue and De Valera recommended it be “withdrawn till further notice” on the 13th of December 1938.

We can see the effects of the Catholicisation of Ireland in the culture and politics of the years following Ireland’s identity crisis.

Contraceptives were illegal in Ireland until 1980, homosexuality was illegal until 1982, and divorce was unconstitutional until 1996.

These are just three examples of the Catholic Church’s influence on the development of the state’s foundational institutions.

The first lines of De Valera’s 1937 Irish Constitution invokes the “Most Holy Trinity”.

This should not come as a surprise once we realise that De Valera’s government sent drafts of this document to the Vatican for approval prior to presenting it to the Irish people themselves. According to 1936 census figures, 5.3% of the population voted (1.2 million) on whether to ratify the new constitution and it passed by a mere 158,160 votes.

Child sex abuse scandals, mass-graves in Church-run orphanages, and an assortment of damning controversies have led to a dramatic shift in attitudes towards the church today, however. The recent passing of the same-sex marriage referendum, resulting in a change to Ireland’s constitutional definition of marriage, indicates just how far many Irish people have departed from their Catholic identity.

As for Walsh’s efforts, I would say they were certainly not in vain, however.

Though ultimately overshadowed by the Church, the Áenach served its purpose of impacting the development of post-colonial Irish identity during its “identity crisis” years of transition by bringing a sense of cultural cohesion and meaning to Irish life.

Of course, this could have been a great legacy for Walsh and one can only imagine how the spectacle of the Áenach might look today, but perhaps it was over-ambitious of Walsh to want to repeat it every four years – perhaps it was premature of Walsh to think it was even necessary?

Whatever the case, it seems that the timing and the execution of the first revived Áenach in 1924 was perfect.

Such conditions could not have been planned in advance, and this opportune moment was the perfect vessel for channelling the idea of a new Ireland in the minds of the people, and with it a sense of an independent Irish identity was secured.

Apart from ongoing hostilities between loyalist and republican factions in the British controlled parts of Ulster, Ireland survived as a relatively peaceful country and went on to become prosperous and confident in its ability to sit at the table of nations.

While the revival of the Áenach was, sadly, not sustained, in 1953, Joe Christle, a lecturer of law and later vice-principal at the Rathmines School of Commerce who had ties to the Republican movement, organised the first ever Rás Tailteann, or the Tailteann Race.

The Tailteann Race is an annual 8-day international cycling stage race making it akin to Ireland’s Tour de France.

Due to the partition of Ireland’s six Ulster counties, competitive cycling in Ireland was being managed by three different organizations (the National Cycling Association, Cumann Rothaiochta na hÉireann (CRÉ) and the Northern Ireland Cycling Federation (NICF)). Being a member of the republican-leaning NCA, Christle longed for a united Ireland, refused to recognise Northern Ireland as a separate entity or to restrict the jurisdiction of the NCA to just the Republic.

So, the Rás was established. By naming the race Rás Tailteann the organisers were associating the cycle race with the Tailteann Games.

Since its founding in 1953, the Rás has been held annually to the current day and sponsored by An Post, the state-owned Irish postal service.

Would you like to see the Áenach Tailteann revived today?

If so, what sort of games and contests would you like to see included?

How do you imagine the opening ceremony would look?