Throughout history, cats have maintained a distinctive and enduring presence, captivating the imagination and affection of millions. Within early Irish society, these enigmatic creatures held considerable significance in various aspects of everyday life, they make appearances throughout Irish mythology and even had protection under the Brehon law.

While it was once thought cats first arrived on Ireland’s shores about 2,000 years ago, recent discoveries have shed light on the existence of European wildcats in the region approximately 3,000 years ago. These indigenous felines, characterized by sturdy features and unique markings, would eventually interbreed with domesticated cats introduced by traders and settlers and these captivating and useful creatures gradually became an integral part of Irish life.

Working cats were indispensable for hunting rodents and pests, and safeguarding crucial grain stores and food supplies. In addition to their practical contributions, these felines also offered companionship and solace as comfort cats. The incorporation of cats into early Irish society demonstrated their adaptability and the profound connection that developed between humans and their feline companions.

Early Medieval Irish Society and the Legal Status of Cats

Early medieval Irish society was characterized by a complex web of relationships and social structures, with society divided into various classes such as kings, nobles, warriors, learned individuals, farmers, and laborers. Within this intricate social landscape, cats held a unique legal status that reflects their diverse roles in Irish life, including both practical and symbolic aspects.

Catslechta is an Old Irish legal text on cats, which was part of a larger compilation called the Senchus Mór. Some fragments of the text are still available, including in TCD ms 1363 and Bodleian Library, Oxford ms Rawlinson B. 506. The tract on what a judge should know lists Catslechta among the requirements. Citations from this text are also found in O’Davoren’s Glossary.

The Catslechta ‘cat-sections’ offer detailed information on the legal protections and classifications of cats. Glossed quotations from this text can be found in the Corpus Iuris Hibernici (CIH), as well as commentary on Catslechta in both CIH and the Zeitschrift für celtische Philologie (ZCP). The legal framework provided by Catslechta not only highlights the practical roles cats played in early Irish society, such as hunting rodents and pests, but also emphasizes the deep connection between humans and their feline companions.

Another important text, Di Chetharṡlicht Athgabála, addresses the ‘four sections of distraint’ related to offenses committed by various animals, such as cows, oxen, pigs, sheep, horses, dogs, cats, and bees. This text underscores the importance of animals in early Irish society and the legal mechanisms in place to deal with offenses involving them.

The legal framework surrounding cats in early Irish society extended beyond their practical roles and protection to include the categorization and valuation of cats based on their unique talents and characteristics. Cat names often reflected their physical appearance, abilities, or the roles they played within the household.

Ameone, for example, referred to a mighty cat known for its vocal prowess, while Aicrúipnei was a highly skilled hunter of rodents, adept at guarding barns, mills, and drying-kilns. Female cats, like Breonei, were recognized for their loud purring and protective nature. Meone, on the other hand, was a pantry cat, safeguarding food stores by catching mice and rats.

Cats also held specialized roles tailored to the needs of various members of the household. Abaircne, a cat for women, was known for its strength and unique white-breasted black coat, while Folum, the herding cat, was kept alongside cows in enclosures. Rincne was a children’s cat, engaging with little ones in playful interactions, either entertaining them or being the subject of their amusement.

Cats in Early Irish Literature, Landmarks, and Divination

The enduring presence of cats in early Irish culture extended beyond practical and legal realms, as they were also prominently featured in the mythology, literature, and folklore of the time. The diverse roles and symbolic meanings of cats in early Irish society attest to their deep cultural significance, permeating every aspect of life, from mythology and literature to landmarks and spiritual practices.

Pangur Bán: A 9th Century Irish Poem About a White Cat Called Pangur

One special relationship between a monk and his cat was immortalised in the Irish language poem called “Pangur Bán,” written in 9th century. The verse eloquently compares the monk’s scholarly pursuits to the hunting prowess of a white cat, illuminating the profound bond between humans and their feline companions.

Though the poem is anonymous, thus making true accreditation difficult, the style and timing of the text bear similarity to the poetry of Sedulius Scottus (roughly translated as ‘the sincere’, or ‘diligent’ Irish man. Scoti being an early descriptor of the Gaelic race which we now find in the name Scotland i.e. the land of the Scots), leading some scholars to speculate it is the work of his hand.

Let’s assume for the purposes of this article that we are looking at the work of this same Sedulius. His poem is about his cat whom he called ‘Pangur the White’ and is composed of thirty-two lines divided into eight verses with four lines each.

(Beginning 15 lines from the bottom of left page)

Pangur Bán Poem and Translation by Séamus Heaney

Pangur Bán

Messe ocus Pangur Bán,

cechtar nathar fria saindán;

bíth a menma-sam fri seilgg,

mu menma céin im saincheirdd

Caraim-se fos, ferr cach clú,

oc mu lebrán léir ingnu;

ní foirmtech frimm Pangur bán,

caraid cesin a maccdán.

Ó ru·biam — scél cen scís —

innar tegdais ar n-óendís,

táithiunn — díchríchide clius —

ní fris tarddam ar n-áthius.

Gnáth-húaraib ar gressaib gal

glenaid luch inna lín-sam;

os mé, du·fuit im lín chéin

dliged n-doraid cu n-dronchéill.

Fúachid-sem fri frega fál

a rosc anglése comlán;

fúachimm chéin fri fégi fis

mu rosc réil, cesu imdis,

Fáelid-sem cu n-déne dul

hi·n-glen luch inna gérchrub;

hi·tucu cheist n-doraid n-dil,

os mé chene am fáelid.

Cía beimmi amin nach ré,

ní·derban cách ar chéle.

Maith la cechtar nár a dán,

subaigthius a óenurán.

Hé fesin as choimsid dáu

in muid du·n-gní cach óenláu;

du thabairt doraid du glé

for mu mud céin am messe.

White Pangur

Pangur Bán and I at work,

Adepts, equals, cat and clerk:

His whole instinct is to hunt,

Mine to free the meaning pent.

More than loud acclaim, I love

Books, silence, thought, my alcove.

Happy for me, Pangur Bán

Child-plays round some mouse’s den.

Truth to tell, just being here,

Housed alone, housed together,

Adds up to its own reward:

Concentration, stealthy art.

Next thing an unwary mouse

Bares his flank: Pangur pounces.

Next thing lines that held and held

Meaning back begin to yield.

All the while, his round bright eye

Fixes on the wall, while I

Focus my less piercing gaze

On the challenge of the page.

With his unsheathed, perfect nails

Pangur springs, exults and kills.

When the longed-for, difficult

Answers come, I too exult.

So it goes. To each his own.

No vying. No vexation.

Taking pleasure, taking pains,

Kindred spirits, veterans.

Day and night, soft purr, soft pad,

Pangur Bán has learned his trade.

Day and night, my own hard work

Solves the cruxes, makes a mark.

Pangur, white Pangur, How happy we are

Alone together, scholar and cat

Each has his own work to do daily;

For you it is hunting, for me study.

Your shining eye watches the wall;

My feeble eye is fixed on a book.

You rejoice, when your claws entrap a mouse;

I rejoice when my mind fathoms a problem.

Pleased with his own art, neither hinders the other;

Thus we live ever without tedium and envy.

W.H. Auden

Credit: LordBoop on DeviantART.com

Cats in Hell: Feline Symbolism in The Book of the Dun Cow

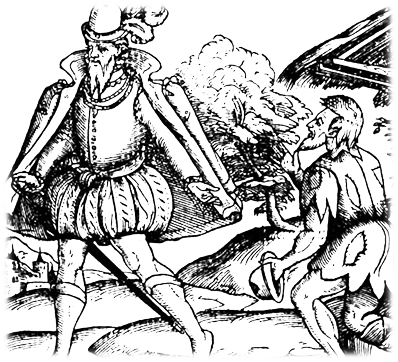

As the centuries progressed, cats continued to play a symbolic role in Irish literature. The Book of the Dun Cow (Lebor na hUidre), a seminal 12th-century Irish manuscript, depicted cats in vivid descriptions of hell and judgment day, underscoring their significance in the mythological and spiritual realms. This symbolic role was further exemplified in early Irish legends that portrayed enchanted, monstrous wild cats like Irusan and Luchthigem. These mystical creatures were said to dwell in caves and challenge brave champions, asserting their place in Ireland’s rich folklore.

Cats and the Landscape

This connection between cats and the mythological world can also be observed in the landscape of Ireland, with landmarks such as the Cave of Cats or Oweynagat in County Roscommon. This ancient site is believed to be an entrance to the otherworld in Irish mythology and is associated with legends of demonic felines. Similarly, the Cat-Stone in County Westmeath is linked to the tale of a monstrous cat called Luchthigem, which was vanquished by a female warrior from Leinster.

The influence of cats in early Irish society even extended to divination practices, specifically the enigmatic ‘Imbas forasna’ technique. The 9th-century bishop-king Cormac mac Cuilennain provided a rather fanciful description of this method, which involved chewing a piece of raw flesh from a pig, dog, or cat, offering it to idols, and placing palms around cheeks before sleeping to receive prophetic visions. St. Patrick, however, denounced Imbas forasna and teinm Ideda for their pagan origins, though he did not object to dfchetal di chennaib, another form of divination.

The Purrfect Companion?

From the domestication of cats to their legal status, mythology, literature, and landmarks, cats played significant roles in various aspects of Irish life. Their diverse talents and characteristics were celebrated through the use of colorful names and categorizations, reflecting their integration into society as both working animals and cherished companions. Despite the passage of time, the enduring presence of cats in Irish culture remains evident today. From the Cat Stone in Westmeath to the Cave of Cats in Roscommon, these felines continue to captivate our imagination and offer a glimpse into a rich cultural heritage. As we continue to appreciate and honor these beloved creatures, we can draw inspiration from the ways in which our ancestors valued and integrated them into daily life.