Background

Pangur Bán or “White Pangur” is an anonymous poem written in Old Irish around the 9th century originating, it is presumed, from the Abbey of Reichenau; a Benedictine Monastery founded on an island of the Rhine River in 724 AD by the itinerant Saint Pirmin.

Download: Pangur Bán a 9th C. Old Irish Poem | The Original Irish Version With 5 Translations

The Abbey once housed a famous scriptorium for manuscript writers and artists and produced such a bounty of beautifully ornate manuscripts that it gave rise to its own stylistic school that was most prominent around the 10th – 11th centuries called the Reichenau School.

The Reichenau Primer manuscript that contains the poem consists of 8 folia and is now housed in the library of St. Paul’s Abbey in Carinthia, Austria. It contains hymnal and grammatical texts written in Latin, some notes on the Aeneid, astronomical and declination tables written in Greek, and lessons about angels; all glossed with Old High German. In addition, the text notably contains poems written in Old Irish, of which, the subject of this article, Pangur Bán is the most well-known. The poem appears among a transcript of Saint Paul’s Epistles.

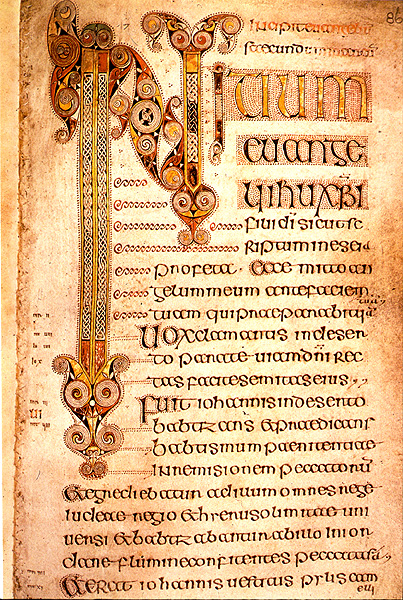

Though this manuscript comes from continental Europe, it is written using ‘insular script’; a stylistic practice that originated in Ireland’s monastic schools that is characterised by its large decorative capital initial letters, ornamented with knot-work, sprials, and dots followed by a diminuendo effect which has the subsequent letters gradually decrease in size until the normal type-size is reached.

(Example of insular script)

This Gaelic style of illumination became influential across all the Continent. It is known that many Irish monks made pilgrimages, were educated, taught, and established monasteries across Europe, particularly after the fall of the Roman Empire.

Bards and Monks

A cursory look at pre-Christian Ireland, and early Irish history in general, brings the Bardic orders into prominent focus. The bards, or file, a word thought to derive from the Proto-Celtic widluios, meaning “seer, one who sees”, were a class of learned individuals who were attendants to the chieftains and great clans of the Gaels.

To call them mere ‘poets’ in the modern sense of the word would be an understatement. They were the keepers of records, successors to the druids, and masters of metric and rhyme through which they wrapped the knowledge of their people, the laws, and histories.

These customs inevitably found their way into the early Christian monastic settlements of Ireland, given that knowledge and poetry went hand in hand in Ireland, this is no surprise. Like the Brehon Laws, the rules and ordnances of the monastery were also composed in poetical rhyme and meter. Alongside the necessary scripture, science, philosophy, and history, we find many poems inscribed in the pages of these beautiful old Irish manuscripts.

Our poem, Pangur Bán, captures the motif found in a lot of Old Irish poetry that depicts an appreciation for nature and an understanding of our place in the natural world by relating oneself to the creatures which God has made; a recurring theme in the Life’s of the Irish Saints, particularly of the earlier saints.

Pangur Bán – Pangur the White

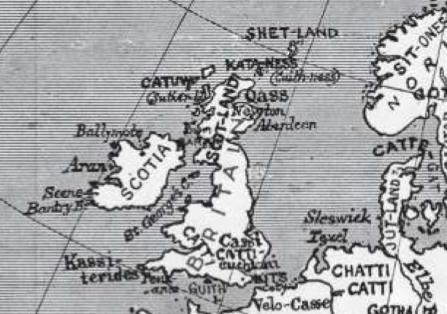

Though the poem is anonymous, thus making true accreditation difficult, the style and timing of the text bears similarity to the poetry of Sedulius Scottus (roughly translated as ‘the sincere’, or ‘diligent’ Irish-man. Scoti being an early descriptor of the Gaelic race which we now find in the name Scotland i.e. the land of the Scots), leading some scholars to speculate it is the work of his hand.

Let’s assume for the purposes of this article that we are looking at the work of this same Sedulius. His poem is about his cat whom he called ‘Pangur the White’ and is composed of thirty-two lines divided into eight verses with four lines each.

Here, he compares his work as a scholar with that of his cat’s work hunting, and the happiness each derives from their own pursuits. His pursuit of knowledge and Pangur’s of mice.

The Poem and Variations

Pangur Bán

Messe ocus Pangur Bán,

cechtar nathar fria saindán;

bíth a menma-sam fri seilgg,

mu menma céin im saincheirdd

Caraim-se fos, ferr cach clú,

oc mu lebrán léir ingnu;

ní foirmtech frimm Pangur bán,

caraid cesin a maccdán.

Ó ru·biam — scél cen scís —

innar tegdais ar n-óendís,

táithiunn — díchríchide clius —

ní fris tarddam ar n-áthius.

Gnáth-húaraib ar gressaib gal

glenaid luch inna lín-sam;

os mé, du·fuit im lín chéin

dliged n-doraid cu n-dronchéill.

Fúachid-sem fri frega fál

a rosc anglése comlán;

fúachimm chéin fri fégi fis

mu rosc réil, cesu imdis,

Fáelid-sem cu n-déne dul

hi·n-glen luch inna gérchrub;

hi·tucu cheist n-doraid n-dil,

os mé chene am fáelid.

Cía beimmi amin nach ré,

ní·derban cách ar chéle.

Maith la cechtar nár a dán,

subaigthius a óenurán.

Hé fesin as choimsid dáu

in muid du·n-gní cach óenláu;

du thabairt doraid du glé

for mu mud céin am messe.

White Pangur

I and Pangur Ban my cat,

‘Tis a like task we are at:

Hunting mice is his delight,

Hunting words I sit all night.

Better far than praise of men

‘Tis to sit with book and pen;

Pangur bears me no ill-will,

He too plies his simple skill.

‘Tis a merry task to see

At our tasks how glad are we,

When at home we sit and find

Entertainment to our mind.

Oftentimes a mouse will stray

In the hero Pangur’s way;

Oftentimes my keen thought set

Takes a meaning in its net.

‘Gainst the wall he sets his eye

Full and fierce and sharp and sly;

‘Gainst the wall of knowledge I

All my little wisdom try.

When a mouse darts from its den,

O how glad is Pangur then!

O what gladness do I prove

When I solve the doubts I love!

So in peace our task we ply,

Pangur Ban, my cat, and I;

In our arts we find our bliss,

I have mine and he has his.

Practice every day has made

Pangur perfect in his trade;

I get wisdom day and night

Turning darkness into light.

– Translation by Robin Fowler.

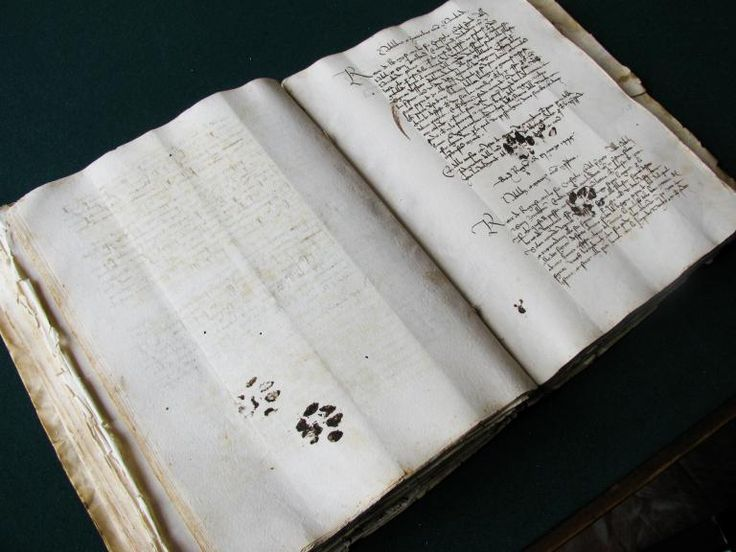

(Beginning 15 lines from the bottom of left page)

The current author’s favourite variation of the poem comes from the Irish poet, playwright and translator, Séamus Heaney, given below.

Pangur Bán and I at work,

Séamus Heaney

Adepts, equals, cat and clerk:

His whole instinct is to hunt,

Mine to free the meaning pent.

More than loud acclaim, I love

Books, silence, thought, my alcove.

Happy for me, Pangur Bán

Child-plays round some mouse’s den.

Truth to tell, just being here,

Housed alone, housed together,

Adds up to its own reward:

Concentration, stealthy art.

Next thing an unwary mouse

Bares his flank: Pangur pounces.

Next thing lines that held and held

Meaning back begin to yield.

All the while, his round bright eye

Fixes on the wall, while I

Focus my less piercing gaze

On the challenge of the page.

With his unsheathed, perfect nails

Pangur springs, exults and kills.

When the longed-for, difficult

Answers come, I too exult.

So it goes. To each his own.

No vying. No vexation.

Taking pleasure, taking pains,

Kindred spirits, veterans.

Day and night, soft purr, soft pad,

Pangur Bán has learned his trade.

Day and night, my own hard work

Solves the cruxes, makes a mark.

A much shorter version of the poem was scribed by the poet Wystan Hugh Auden and comprised of just ten lines, given below.

Pangur, white Pangur, How happy we are

W.H. Auden

Alone together, scholar and cat

Each has his own work to do daily;

For you it is hunting, for me study.

Your shining eye watches the wall;

My feeble eye is fixed on a book.

You rejoice, when your claws entrap a mouse;

I rejoice when my mind fathoms a problem.

Pleased with his own art, neither hinders the other;

Thus we live ever without tedium and envy.

And below, we offer one more variation for your enjoyment, penned by an anonymous author:

I and White Pangur, each of us in his special craft. His mind is set on hunting; my mind is on my special subject.

I love resting (better than any fame) at my book, with diligent understanding; White Pangur is not envious of me; he loves his childish craft.

When we are (tale without tiredness), in our house, being alone, we have an endless sport, a thing to which we may apply our skill.

It is usual, at times, by feats of valor, that a mouse sticks in his net. As for me, there falls into my net, a difficult rule with hard meaning.

He points fiercely against an enclosing wall his eye, bright, perfect. I myself direct against the keenness of knowledge my sharp eye, though it be quite weak.

He is happy with swiftness of movement upon a mouse sticking in his sharp paws. Which I understand a difficult pleasant problem, as for me, I am happy, too.

Though we may be indeed (like this) at any time, neither disturbs his partner; good to each of us is his art, each rejoices in them.

He himself is master of it, the work which he does every day. To bring clarity to difficulty, I am at my own work.

Anonymous

Pangur Bán and The Secret of Kells

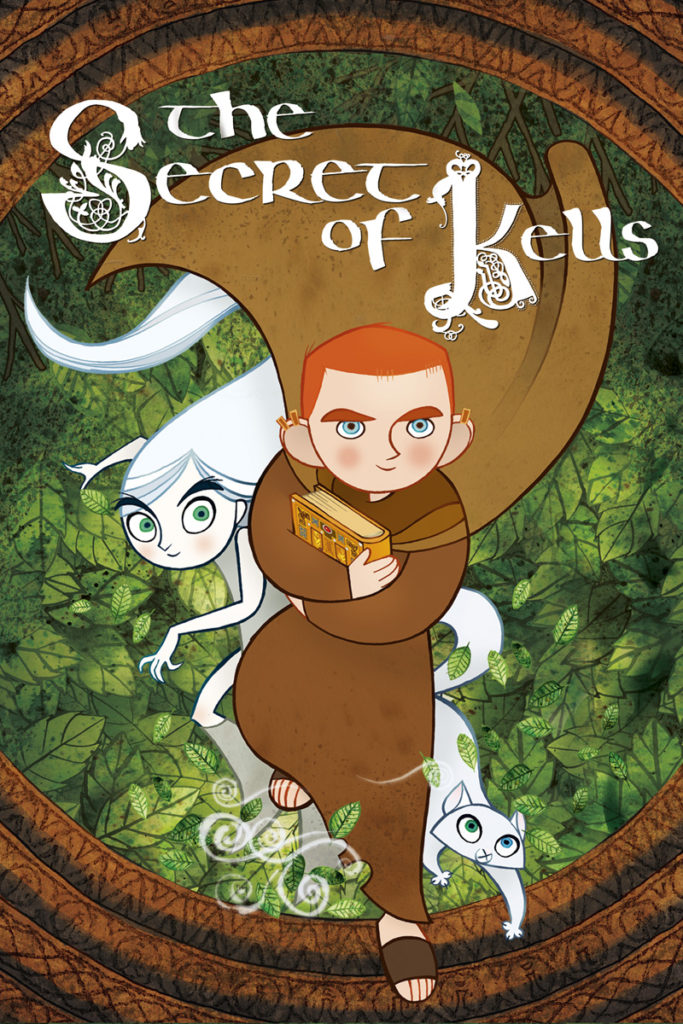

Our beloved white Pangur is not only to be found in old manuscripts and poetical retellings. Even in our modern age, the legend of Pangur lives on in the hearts and minds of the young through the stunning 2009 animated movie The Secret of Kells.

Here Pangur is depicted as the white cat belonging to one of the main characters, a monk called Brother Aidan. The story does not tell us much about Pangur’s history except that she (in the story she is female while the use of Old Irish in the poem seems to depict a male tom cat) has been a companion of Brother Aidan for a long time and may have even accompanied Aidan’s teacher beforehand, the great Saint Colmcille (aka Columba).

During the film, there is a beautiful song sung by Aisling, a Fairy-type character who is a princess of the forest and whose name in Irish translates as ‘dream’. She uses her song to call on Pangur to help her by going ‘where I cannot’.

Aisling’s Song

You must go where I cannot,

Pangur Bán Pangur Bán,

Nil sa saol seo ach ceo,Is ni bheimid beo,

ach seal beag gearr.

Pangur Bán Pangur Bán,Nil sa saol seo ach ceo,

Original

Is ni bheimid beo,

ach seal beag gearr.

You must go where I cannot,

Pangur Ban Pangur Ban,

There is nothing in this life but mist,And we are not alive,

but for a little short spell.

Pangur Ban Pangur Ban,There is nothing in this life but mist,

Literal translation.

And we are not alive,

but for a little short spell.

By: Kevin Flanagan, April 2021

Note: Featured cover image is taken from a 15th C. Manuscript from Dubrovnik, Croatia.

These are not Pangur Bán’s paw prints, but it was too perfect not to use here.

Pingback: Pangur Bán Old Irish Poem | The Original Irish Version With Four Translations - The Brehon Academy

Pingback: Purring Through Irish History: Learn About The History of Cats in Early Irish Society, Legend, and Law - The Brehon Academy