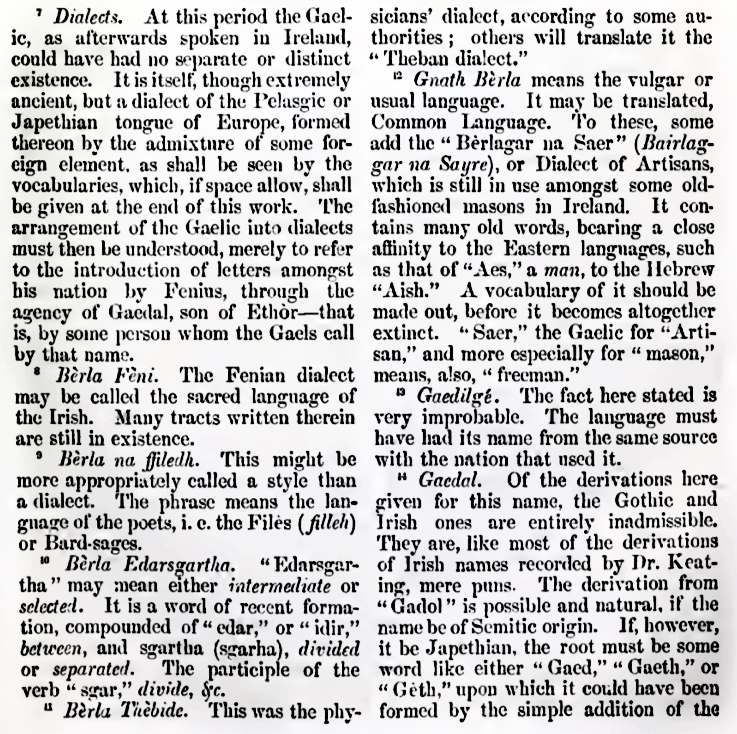

Did you know that early Ireland boasted a remarkable array of official dialects, each tailored to specific societal roles? And while the modern Irish word “béarla” refers to the English language, it originally meant simply “speech” in Old Irish—an umbrella term for the diverse ways the Gaelic people expressed themselves.

Among the most intriguing of these ancient dialects were Bérla Féini, Bérla na Filidh, Bérla Thébide, and Gnath Bérla.

Far from being mere variations of a single tongue, these dialects were distinct linguistic systems, reflecting the sophistication and stratification of early Irish society. Let’s explore each in detail, uncovering their origins, purposes, and the cultural worlds they inhabited.

Bérla Féini:

The Language of Law and Tradition

Bérla Féini, often translated as the “language of the Féni,” was the dialect of Ireland’s ancient legal class, the Brehons. The Féni were the free, land-owning Gaelic people, and their language of law was a cornerstone of the Brehon legal system, a complex code that governed everything from property disputes to personal honor.

This dialect, preserved in texts like the Senchas Már (a vast collection of legal traditions), was highly technical, steeped in archaic vocabulary and formulaic phrasing that ensured precision and continuity.

Unlike modern legal jargon, which often alienates laypeople, Bérla Féini was a living tradition, orally transmitted by Brehons who memorized vast tracts of law. Its syntax and lexicon were deliberately conservative, resisting the natural evolution of spoken Irish to maintain its authority and sanctity.

Terms like cáin (law or tribute) and fír flathemon (the ruler’s truth) peppered this dialect, embedding it deeply in the socio-political fabric of early Ireland.

For the Brehons, mastery of Bérla Féini was not just a skill but a mark of their elite status, distinguishing them as arbiters of justice in a society without centralized courts.

Bérla na Filidh:

The Poetic Tongue of the Learned

If Bérla Féini was the voice of law, Bérla na Filidh—the “language of the poets”—was the song of Ireland’s intellectual and artistic elite, the filí.

These poet-scholars were far more than entertainers; they were historians, genealogists, and propagandists, wielding words as both weapon and shield. Bérla na Filidh was their esoteric dialect, deliberately crafted to be opaque to outsiders. It was dense with allusion, metaphor, and a vocabulary so rich and obscure that it bordered on a secret code.

This dialect evolved from the rigorous training of the filí, who spent years in bardic schools mastering metrics, mythology, and the art of satire—a feared tool that could ruin reputations.

Texts like the Auraicept na n-Éces (The Scholars’ Primer) hint at its complexity, describing a language layered with rosc—rhythmic, alliterative prose—and ogham, an early script that added a cryptic flair.

Words might shift meaning depending on context, and entire compositions could serve as riddles, accessible only to those initiated into the filí’s craft.

For example, a single term like dán could mean “poetry,” “skill,” or “destiny,” depending on its poetic frame.

Bérla na Filidh wasn’t just speech; it was the performance, power, and preservation of Ireland’s oral heritage.

Bérla Thébide:

The Physician’s Dialect of Healing

Less documented but equally fascinating was Bérla Thébide, the “physician’s dialect,” spoken by Ireland’s early healers.

Medicine in medieval Ireland was a blend of practical herbalism, spiritual ritual, and inherited knowledge, often passed down through families of hereditary physicians. Bérla Thébide encapsulated this world, serving as a specialized jargon that distinguished medical practitioners from other learned classes. Its name, possibly linked to “téibid” (related to cutting or surgery), suggests a focus on the healer’s craft, though its exact etymology remains debated.

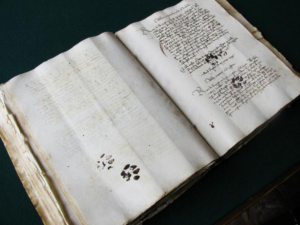

This dialect was rich with terms for ailments, remedies, and anatomical knowledge, much of it recorded in manuscripts like the Book of the O’Lees, a 15th-century medical compendium rooted in earlier traditions.

Words like slán (health or wholeness, but also used today to bid farewell) and líaig (physician) anchored its lexicon alongside detailed descriptions of plants like lus na cnámh mbriste (comfrey, or “the herb of broken bones”).

Bérla Thébide likely incorporated Latin influences as Irish scholars engaged with continental medicine, yet it retained a distinctly Gaelic character. For the physicians, this dialect was a badge of expertise, marking their role as caretakers of both body and soul in a society where illness often carried supernatural weight.

Gnath Bérla:

The Vulgar Dialect of the Common Folk

In stark contrast to these elite tongues stood Gnath Bérla, the “vulgar dialect” or “common speech.” This was the everyday language of the masses—farmers, laborers, and families who lived outside the rarified circles of law, poetry, and medicine.

While the term “gnath” (meaning “usual” or “customary”) might suggest simplicity, this dialect was no less vital. It was the heartbeat of daily life, flexible and evolving, free from the rigid conventions of its specialized counterparts.

Gnath Bérla likely varied by region, reflecting local accents and idioms, though few written records survive to capture its nuances. It was the language of storytelling by the fire, of haggling at markets, and of songs sung in the fields.

Where Bérla na Filidh might cloak a tale in layers of allegory, Gnath Bérla told it straight, with earthy humor and directness. Its speakers were the backbone of Gaelic society, and their dialect bridged the gap between the learned and the lived, ensuring that Old Irish remained a vibrant, communal tongue.

A Shifting Legacy

These dialects—Bérla Féini, Bérla na Filidh, Bérla Thébide, and Gnath Bérla—paint a picture of early Ireland as a linguistic mosaic, where speech was tailored to purpose and prestige. Yet, as Christianity brought Latin and Viking incursions introduced Norse, Old Irish began to shift. By the Middle Ages, Norman influence and later English dominance eroded these specialized dialects, folding them into Middle Irish and beyond. The word “béarla,” once a broad term for speech, narrowed to mean English, a poignant symbol of colonization’s impact.

Still, traces of this rich past linger in Irish literature, placenames, and the modern Gaeilge we know today. The dialects of Old Irish weren’t just ways of speaking—they were ways of being, each a thread in the tapestry of a culture that valued words as much as deeds. From the Brehon’s rulings to the filí’s verses, the physician’s cures to the farmer’s tales, Old Irish sang in many voices, and its echoes still resonate if we listen closely.