The ancient lands of Ireland and Egypt, separated by vast distances and contrasting landscapes, might seem unlikely counterparts in the annals of history. Yet, whispers of connections between the two civilisations have persisted for centuries. From artefacts suggesting trade to mythological tales intertwining their destinies, the potential intersections between the Irish and Egyptian peoples beckon exploration. While the exact nature of their relationship remains shrouded in mystery, the hints of intercultural exchange offer a tantalizing glimpse into a shared past. This investigation delves into the evidence, both tangible and anecdotal, that links the Emerald Isle with the Land of the Pharaohs.

Mythological Evidence for an Irish-Egyptian Connection

The annals of mythology and legend hold tales that blur the lines between fact and fiction. One such captivating narrative suggests an intertwining of Irish and Egyptian stories, painting a picture of shared mythos and deep-rooted connections. Dive into the ancient stories that hint at a relationship between these two distinct cultures.

The Legend of Queen Tea Tephi: Ancient Jerusalem, Egypt, and Irish Mythology

Tea Tephi is a captivating figure that has been woven into the tapestry of Irish legends. Her story serves as an intricate nexus that binds the biblical lands of Jerusalem and Egypt to the lush green shores of Ireland. Unravelling her tale takes us through a journey of exile, refuge, and eventual rise to queenhood in Ireland. Much of what is said about her has its roots in folklore and cannot, therefore, be universally accepted as historical fact.

The Princess from the House of David and Her Connection to Egypt:

Originating from the House of David, Tea Tephi belonged to the royal lineage of Jerusalem, representing a bridge between biblical narratives and Irish folklore. The destruction of the First Temple in 586 BCE in Jerusalem acts as a pivotal point in her story. Following this cataclysmic event, she was supposedly exiled, marking the beginning of her odyssey.

In the aftermath of the temple’s destruction, Tea Tephi was taken under the wings of the Prophet Jeremiah. This chapter of her story paints a vivid picture of the princess seeking refuge in Egypt. The intersections of her lineage with Egyptian royalty come into play here. Various accounts link her to Pharaoh Hophra (also known as Apries), hinting that she might have been considered as a potential diplomatic bride or that Jeremiah received her as a gift. This association with Egyptian royalty enriches her tale, infusing it with the mystique of the Nile Valley.

A New Beginning in Ireland:

The legend continues with Tea Tephi embarking on a journey to the west, reaching the shores of Ireland. Here, destiny had charted a royal path for her once again. She is said to have married a Milesian prince named Eochaid mac Eirc. Their union symbolizes the merging of two royal bloodlines – the biblical House of David and the Milesian dynasty of Ireland. Together, they founded the Kingdom of Tara, establishing a new era of peace and prosperity in Ireland. This act etches her name as a central figure in the annals of Irish legends.

The Multiple Layers of Her Legacy:

The stories surrounding Tea Tephi are manifold, with variations that extend her lineage to different pharaohs or even conflate her identity with other legendary figures like Scota. Some versions even delve into her bringing precious relics to Ireland, such as the “Jodham Morain” (priest’s breastplate), the harp of King David, and the revered Coronation Stone. These items not only signify her royal lineage but also further solidify the Hebrew identity of her people in Irish legends.

She is also credited as the source for the name of Cnoc Teamhair, the Hill of Tara, which legends describe as the seat of Irish high kings and historical evidence confirms as a site of royal significance for millennia. Here, the name is derived from Tea (her name) and mur (a tower or rampart) giving us a meaning of ‘Tea’s rampart’.

Relate to me O learned Sages,

A poem from the Metrical Dindsenchas (the Lore of Place Names).

When was the place called Temor?

Was it in the time of Parthalon of battles?

Or at the first arrival of Caesaire?

Tell me in which of these invasions

Did the place have the name of Tea-mor?

O Tuan, O generous Finchadh,

O Dubhan, Ye venerable Five

Whence was acquired the name of Te-mor?

Until the coming of the agreeable Teah

The wife of Heremon of noble aspect.

A Rampart was raised around her house

For Teah the daughter of Lughaidh (God’s House)

She was buried outside in her mound

And from her it was named Tea-muir.

Cathair, Crofin not inapplicable.

Was its name among the Tuatha-de-Danaan

Until the coming of Tea – the Just

Wife of Heremon of the noble aspect?

A wall was raised around her house

For Tea the daughter of Lughaidh,

(And) she was interred in her wall outside,

So that from her is Tea-mor.

A habitation which was a Dun (Hebrew court) and a fortress

Which was the glory of murs without demolition,

On which the monument of Tea after her death,

So that it was an addition to her dowry.

The humble Heremon had

A woman in beautiful confinement

Who received from him everything she wished for.

He gave her whatever he promised,

Bregatea a meritorious abode

(Where lies) The grave, which is the great Mergech

The burial place which was not violated.

The daughter of Pharaoh of many champions

Tephi, the most beautiful that traversed the Plain.

She gave a name to her fair cahir,

The woman with the prosperous royal smile,

Mur-Tephi where the assembly met.

It is not a mystery to be said

A Mur (a rampart or tower) (was raised) over Tephi I have heard.

Strength this, without contempt,

Which great proud Queen have formed

The length, breadth of the house of Tephi,

Sixty feet without weakness

As Prophets and Druids have seen.

We may never know the full truth of Tea Tephi’s legacy, however, her story provides a beautiful testament to the interconnectedness of cultures and histories. While her tale is embedded in the realm of mythology, it provides a unique vantage point, offering glimpses into how ancient civilizations might have intertwined their narratives to forge shared legacies.

The Hill of Tara or the Hill of Torah: Was The Arc of the Covenant Brought to Ireland?

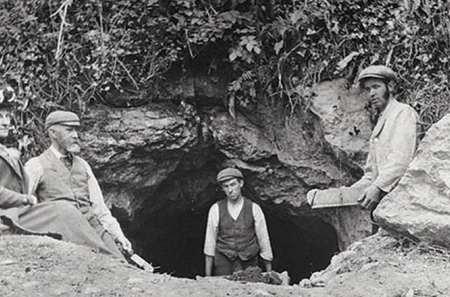

A little-known curiosity of Irish history further emphasizes a Hebraic connection to Ireland when, between the years 1899 and 1902, a group from the British-Israel Association of London arrived in County Meath with the intention to excavate the Hill of Tara. Convinced that the Ark of the Covenant, a chest believed to house the stone tablets of the Ten Commandments, was buried there, these ‘British-Israelites’ engaged in bizarre and illegal digging activities.

This excavation drew sharp condemnation and led to a protest spearheaded by eminent cultural personalities such as William Butler Yeats, Douglas Hyde, and Maud Gonne. They expressed their dissent by lighting a bonfire and singing ‘A nation once again’ at Tara. The media also sided with the protestors, making it the inaugural media crusade in defence of a national monument. This theory implies that Hill’s proper name is derived from the Hill of Torah. The Lia Fail, or Stone of Destiny, that once stood here as a coronation stone of the Milesian race is also often linked to Jacob’s Pillar. For more information on this topic see Tara and the Ark of the Covenant by Mairéad Carew.

The Legend of Scota: The Pharaonic Queen of the Scots and the Gaels

Scota (or Scotia) is yet another captivating figure from Irish mythology, shrouded in tales of migration and ancient connections to distant lands. Her legend is often intertwined with the legend of Tea Tephi, as she also stands as a symbol of the melding of histories and mythologies that make up the tapestry of Ireland’s past. Her narrative intertwines with the tales of migration, epic voyages, and the founding of ancient cities, embodying the deep connection between Ireland and Egypt.

Origins and Legends:

Scota’s legend is deeply rooted in the annals of Irish mythology. While certain accounts tie her as a descendant of an Egyptian Pharaoh, others intertwine her tale with that of Tea Tephi. A persistent feature of her legend maintains that the Scots, an early or alternative name for the Irish, the Gaels, and later the people of Scotland, derive their name from this enigmatic Egyptian princess. There’s even talk of the famed Stone of Destiny or the Lia Fáil, pivotal in the crowning of Irish kings, being brought to Ireland’s shores by Scota herself.

Despite the historical gaps, the story of Scota and her Egyptian roots continues to captivate. It speaks to a broader narrative – one of intertwined histories, shared legacies, and the global interconnectedness of ancient civilizations. The very idea that Ireland, with its unique cultural tapestry, could share ties with the grandeur of ancient Egypt is a testament to the island’s rich oral tradition and its longstanding fascination with its origins.

Dublin: A City Born from Legend?

Arguably, the most riveting part of Scota’s story is the claim that she founded Dublin. The city, known as “Dubh Linn” in ancient times, which translates to “black pool,” is said to owe its name and perhaps its very founding to Scota. Yet, juxtaposing this mythical account with historical records yields a contrasting story. Claudius Ptolemy, the renowned geographer of the 2nd century CE, gives us the earliest known reference to a settlement that might be Dublin, naming it “Eblana.” In his detailed records, there’s a conspicuous absence of any mention of Scota. Fast-forward a few centuries, and it’s the Vikings in the 9th century CE who get credited with Dublin’s establishment, pushing the legend of Scota association to this location further into the realm of mythology.

While Scota’s tale might tread the thin line between myth and history, it underscores a significant aspect of Ireland’s cultural identity. Myths, after all, are not just stories but reflections of a society’s aspirations, beliefs, and understanding of its past. The enduring legend of Scota, with its Egyptian connection, serves as a testament to Ireland’s rich mythological heritage and its penchant for weaving intriguing tales of yore.

Archaeological Evidence for an Irish-Egyptian Connection

Among such intriguing links is the potential connection between Ireland and Egypt, hinted at by archaeological discoveries that weave a compelling narrative. Let’s delve into the evidence that suggests these ancient civilizations might have crossed paths.

The Faddan More Psalter: Irish Prayers on Egyptian Papyrus

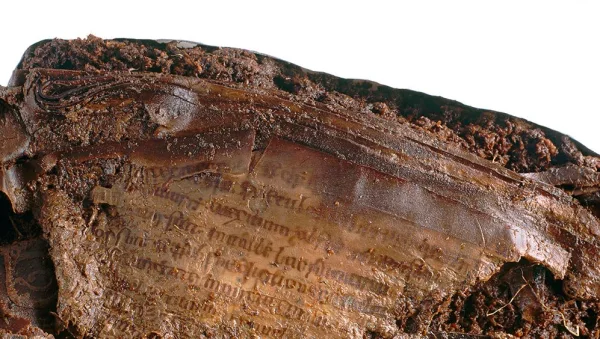

The mention of Egyptian monks in Ireland is supported by the discovery of an ancient book in a bog in County Tipperary in 2006. The book, Egyptian in style and with pages made of papyrus, hints at this connection between Ireland and Egypt.

The “Faddan More Psalter” is a 1,200-year-old illuminated vellum manuscript found in a peat bog near Birr, County Tipperary, Ireland. Notably, its leather binding contains fragments of Egyptian papyrus, suggesting a historical link between early Irish Christianity and the Middle Eastern Coptic Church. The manuscript, likely produced in an Irish monastery, comprises Latin-written psalms, of which about 15% have survived. Researchers believe the leather, potentially of Egyptian origin, may have travelled through regions such as the Holy Land, Constantinople, or Rome before reaching Ireland. Discovered by Eddie Fogarty in 2006, the psalter underwent two years of restoration at Trinity College Dublin, revealing the papyrus fragments. The National Museum in Dublin plans a public exhibition of the artefact.

This discovery does not prove conclusively that this connection was strong, or even that movement of people was common between these two civilisations, but at the very least it is evidence of a connection of trade and ideas. There is evidence that indicates a trade route between the eastern Mediterranean and Britain since the Bronze Age, primarily due to the demand for Cornish tin, essential in crafting bronze tools and weapons.

Detail of the Faddan More Psalter, before conservation.

Ireland and The Pharaoh’s Necklace

In the 1950s, a significant archaeological discovery was made by Dr. Sean O’Riordan of Trinity College. While excavating at Tara in Ireland, he uncovered the skeletal remains of a young prince. Intriguingly, adorning the skeleton was a necklace composed of “faience beads”. A subsequent carbon dating of the skeleton traced its origins to around 1350 BC. Further heightening the intrigue, J. F. Stone and L. C. Thomas, scholars in the field, asserted that these beads bore a remarkable resemblance to Egyptian craftsmanship. In fact, they concluded that the beads were “identical” to those found on the famed Egyptian Pharaoh, King Tutankhamun.

Example of faience beads.

Only a few years later, in 1955, Dr O’Riordan made another significant find at the Mound of Hostages, again at Tara. He uncovered skeletal remains, this time of a young boy, which was also carbon-dated to the same period, around 1350 BC. Accompanying this skeleton was another necklace, made of faience beads, that not only matched the Egyptian design and production methods but also closely resembled the collar found on Tutankhamun, who lived contemporaneously with the young boy from Ireland. These findings, as reported by Ancient Origins, further suggest intriguing links between ancient Ireland and Egypt.

The Desert Monks: The Influence of Egyptian Christianity on the Early Irish Church

The Stowe Missal is an early Irish liturgical manuscript written in the 8th century. It is one of the most important sources of information about early Irish Christianity. The manuscript contains a number of prayers and hymns, as well as a calendar of saints. One of the most interesting passages in the Stowe Missal is a prayer that mentions the desert monks, and in particular, Anthony of Egypt. The prayer reads:

May God protect us from the dangers of the desert, and may he grant us the grace of following the example of Anthony of Egypt.

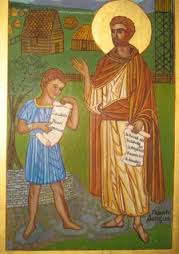

Anthony of Egypt was a famous early Christian monk who lived in the 3rd and 4th centuries. He is considered to be the founder of Christian monasticism. Anthony left his home and family to live in the desert, where he devoted himself to prayer and asceticism. He became a popular figure, and many people came to him for guidance and spiritual advice. The teachings of Anthony of Egypt had a profound impact on early Irish Christianity. Irish monks were inspired by his example of asceticism and his commitment to prayer. They also adopted many of his practices, such as solitary living and the use of the desert as a place of spiritual retreat.

The passage above suggests that there was a connection between early Irish Christianity and the desert monastic tradition of Egypt. It is possible that some Irish monks travelled to Egypt to study with the desert fathers, and that they brought back with them the teachings of Anthony of Egypt.

In addition to the Stowe Missal, there are a number of other early Irish sources that mention the desert monks. These sources include the Book of Armagh, the Book of Leinster, and the Annals of the Four Masters. These sources suggest that there was a significant interest in the desert monastic tradition in early Ireland.

The Litany of Irish Saints by Oengus of Tallaght (fl. 800) also mentions the burial of seven Egyptian monks in County Antrim. The passage reads: In Uillaigh, Co. Antrim, seven Egyptian monks (manchaib Egipt) were buried. The passage does not give any further details about the monks, such as their names or the date of their death. However, it does suggest that there was a community of Egyptian monks in County Antrim in the 8th century. The evidence suggests that there was a connection between Ireland and Egypt in the 8th century, and that some Egyptian monks may have travelled to Ireland. Reference to the burial of seven Egyptian monks in County Antrim is a reminder of this connection, and it is a fascinating piece of Irish history.

Born into the royal house of Ulster, Saint Óengus mac Óengobann, also known as Óengus the Culdee, was a 9th-century Irish bishop and writer. Joining the Tallaght monastery incognito, his teaching gifts were eventually discovered by the abbot, St. Maelruain, with whom he collaborated on the Martyrology of Tallaght.

He studied at Clonenagh and later sought solitude as a hermit at Dysert-Enos. The word dysert appears in many Irish place names and is pronounced ‘desert’, meaning a sacred deserted place for worship.

The interest in desert monks in early Ireland is likely due to a number of factors. First, the Irish were familiar with the desert through their trade links with the Mediterranean. Second, the Irish were attracted to the asceticism and spirituality of the desert monks. Third, the Irish were looking for a way to renew their own religious life, and they saw the desert monks as a model for this renewal.

A High Cross at Dysert O’Dea (O’Dea’s desert or sanctuary), Co. Clare.

The Irish term disert, meaning a solitary place, finds itself embedded in many Irish place names, further hinting at this Egyptian influence. This interest in the desert monks in early Ireland seemingly had a formative impact on Irish Christianity. The Irish adopted many of the practices of the desert monks, such as solitary living and the use of the desert as a place of spiritual retreat. The Irish also developed their own unique monastic tradition, which was influenced by the desert tradition. This distinctly Irish monastic tradition played a significant role in the development of Christianity in Europe, particularly after the collapse of the Roman Empire, and it continues to be influential today.

Coptics and Celtics: The Artistic Connection

Renowned scholar Robert Ritner has drawn attention to striking similarities between Irish and Coptic Christian art forms, suggesting a potentially shared or influenced artistic tradition. Unique Egyptian motifs, which diverge from the standard Roman Christian traditions prevalent in Western Europe, appear prominently in Irish artefacts and sculptures.

For instance, there’s a significant presence of the handbell in both cultures. In the Coptic tradition, a bishop receives this during his consecration. Similarly, this motif can be observed in the 8th-century Bishop’s Stone located in Killadeas, County Fermanagh. There’s a distinct preference in Ireland for the T-shaped “Tau cross” for bishops, differing from the common shepherd’s crook found in Western Europe, though the Latin churches occasionally did use the Tau cross. Interestingly, Irish bishops are often portrayed without the traditional mitre. Instead, they are depicted with a crown adorned with a jewel.

Moreover, early medieval Irish high crosses frequently feature Egyptian monastic pioneers, such as St. Antony and Paul of Thebes. While some argue this could be attributed to Jerome’s Life of Paul, which popularized the life of Antony in the West, the consistent depiction cannot be ignored. Perhaps the most compelling evidence is found in the Book of Kells, a Celtic masterpiece from around 800 AD. Within its intricate illustrations, angels are depicted holding flabella, processional fans typical of the eastern Mediterranean region, primarily used for cooling esteemed individuals.

Considering Ireland’s climate, such imagery seems out of place and strongly indicates an artistic influence from the Coptic tradition. For more information see Ritner, Jr., Robert K. “Egyptians in Ireland: A Question of Coptic Peregrinations.” Rice Institute Pamphlet – Rice University Studies, 62, no. 2 (1976) Rice University.

The Gaelic Phoenician Connection

The theory that the Gaels are descended from Phoenicians is an old one, and it has been supported by a number of linguistic and cultural similarities between the two groups.

One of the most striking similarities is the name of the god Bel. The pre-Christian Gaels worshipped a god called Bel, which is the same name as the god of the Phoenicians, who is often rendered as Baal. Bel was a god of fire and light, and he was often depicted as a bull. The Gaels also celebrated a holiday called Beltane, which is thought to be a festival of Bel. Beltane is celebrated on May 1st, and it is a time of celebration and fertility.

Another similarity between the Phoenicians and the Gaels is the use of the word “cathair” for a citadel or fortress. The Phoenician word for citadel is “qatra“, and the Gaelic word for citadel is “cathair” (compare with Welsh caer). The two words are very similar, and they suggest that the Gaels may have borrowed the word from the Phoenicians.

The Phoenicians were also known for their skill in navigation and trade, and they established colonies throughout the Mediterranean. This suggests that they may have had contact with the Gaels, and that they may have influenced their culture.

The use of bagpipes and kilts in Ireland is also thought to be a legacy of the Phoenicians. The bagpipes are thought to have originated in Egypt, and they were adopted by the Phoenicians. The kilt is also thought to have originated in the Middle East, and it was adopted by the Phoenicians. The Phoenicians may have brought these instruments and garments to Ireland, where they were adopted by the Gaels.

Of course, there is no concrete evidence to prove that the Gaels are descended from Phoenicians. However, the linguistic and cultural similarities between the two groups are suggestive, and they support the theory that there was some contact between the two groups in the past.

It is also worth noting that the theory that the Gaels are descended from Phoenicians is not without its critics. Some scholars argue that the similarities between the two groups are not significant enough to warrant the claim of a common ancestor. They also argue that the Phoenicians were not known for their seafaring skills, and that they are unlikely to have travelled to Ireland.

Ultimately, the question of whether or not the Gaels are descended from Phoenicians is a matter of debate. There is no clear consensus on the issue, and the evidence is inconclusive. However, the linguistic and cultural similarities between the two groups are suggestive, and they support the theory that there was some contact between the two groups in the past.

The narrative of an Irish-Egyptian connection, while dotted with archaeological, mythological, and artistic evidence, remains an enigma. Both cultures boast rich histories, and the overlaps, whether by coincidence or contact, are undeniably captivating. Yet, while the allure of a deep-rooted bond between Ireland and Egypt persists, concrete evidence is sparse. What’s clear is that the possibility ignites imagination and scholarly curiosity. As with many historical mysteries, only further research and potential new discoveries will shed definitive light on the true nature of this connection.