“The Scottish historian Pinkerton, who was hardly sympathetic, admits: ‘Foreigners may imagine that it is granting too much to the Irish to allow them [the Irish] lists of kings more ancient than those of any other country of modern Europe.

But the singularly compact and remote situation of that Island, and the freedom from Roman conquest, and from the concussion of the Fall of the Roman Empire, may infer this allowance not too much.”

– Seamus MacManus, The Story of the Irish Race, p12

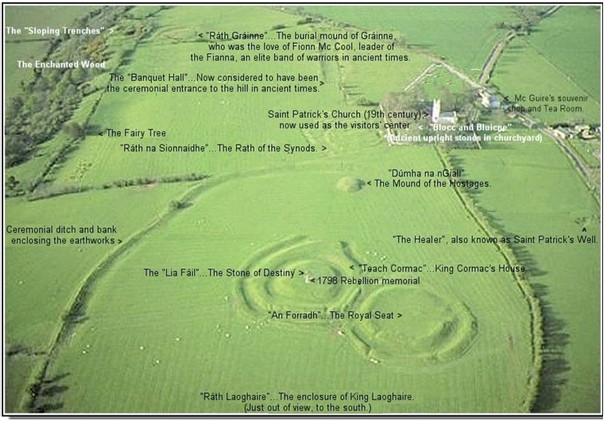

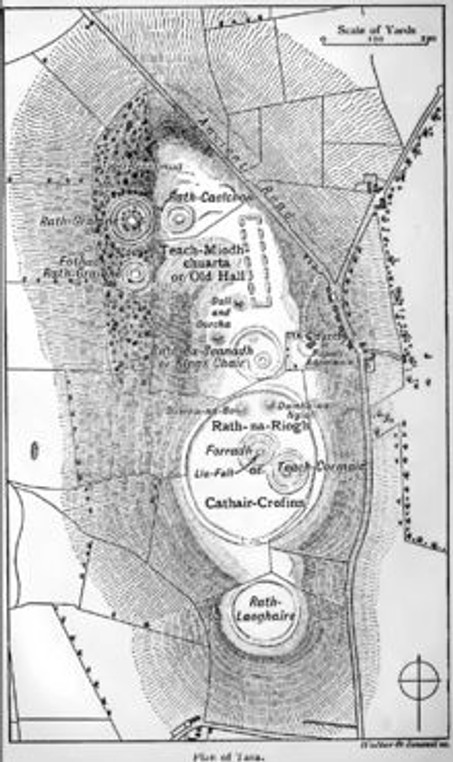

Situated in County Meath, not far from Kells, Teamhair na Rí (Tara of the Kings) was the Royal Seat of the High-Kings of Ireland in times long since past.

Stories associated with the Hill of Tara weave a colourful tapestry of mythology, folklore and real history to reveal a centre of learning, justice and power very worthy of our consideration.

Even through the mists of time and centuries of conquest, the Hill of Tara remains one of Ireland’s best known and most loved Neolithic sites, bearing perhaps unrivalled political, social and religious significance.

When approaching the Hill of Tara one makes a gentle descent up the same ancient road that was walked by great kings and chieftains, and much later by the Catholic Emancipator, Daniel O’Connell, on his way to give an address at one of his great monster-rallies on the summit of the Hill. Entering through a modest gate we walk up a stone path towards a small Church passing a statue of Ireland’s Patron Saint Patrick on the way. Moving on through an old peaceful graveyard one suddenly finds themselves in a vast open space with breathtaking views, just shy of 155m above sea-level. It is said that up to 16 counties can be seen from the summit of the Hill on a clear day, which unfortunately doesn’t happen often enough in Ireland!

A series of mounds and trenches are the only remnants of this Gaelic palace. Signs are posted to tell visitors that this mound was the legendary ‘King Cormac’s House’ or those mounds were the ‘Banqueting Hall’ or that other mound was the ‘Mound of Hostages’, but these fall far short in aiding our picturing and understanding of Teamhair na Rí in its full glory.

Descriptions of Tara

“There were five main roads leading from Tara through the country in different directions; and numerous minor roads – all with distinct names – are mentioned in the annals.”

P.W. Joyce, A Short History of Ireland from the Earliest Times, p.117

The following extracts are taken from The Story of the Irish Race by Seamus MacManus (available for free download in the Brehon Law Academy’s Resource Section), chapter XI. Tara, pp. 54-57. (Click through the images to enlarge.)

The Mythological Origins of

Ireland’s Ancient Seat of Rule

The Lebor Gabála Erenn or Book of the Taking of Ireland (modern Irish: Leabhar Gabhála Éireann) contains a portion of Ireland’s epic mythology depicting the successive migrations and battles among various groups of Ireland’s early mythic peoples. These stories were written down, albeit from much earlier accounts, by monks from around the 7th-8th Centuries. While disregarded today as pseudo-history and myth these stories were once considered to depict real historical events. To focus on all the intricate details would take up too much space for a discussion on this topic so we will only consider some of these aspects as they relate to our Hill of Tara.

The Firbolgs (along with the Fir Gáilióin, and Fir Domnnann) are said to be the first people to occupy a kingship at the site now known as Cnóc Teamhair – the Hill of Tara. They held this for 34 years until the coming of the Túatha Dé Danann. The tribes making up the Firbolgs are said to be descendents of an earlier group of Irish inhabitants called the Clann Nemid, Family of Nemed (nemed also means ‘noble’ in early Irish), who were driven out of Ireland to Greece centuries earlier by the feared northern sea-fearing tribe called the Fomorii or Formians.

Eochaid Mac Eirc was the Firbolg King at the time the Túatha Dé Danann arrived. Some accounts suggest that the TDD were also descendents of this same Clann Nemid; which explains why these different peoples could understand one another’s language when they first sent their heroes, Bres of the TDD and Sreng of the Firbolg, to meet diplomatically. Unable to strike up peaceful terms, the Firbolg and TDD went to battle at the famous Cét-chath Maige Tuired or First Battle of Mag Tuired (Moytura). Having defeated the Firbolgs at a fair battle the TDD assumed the position as rightful rulers and chose Tara as to continue as the seat of royal Irish kingship.

There is no doubt from the literature that comes down to us that this tribe known as the Túatha Dé Danann were viewed with mystical reverence.

On one hand they are portrayed as great law-givers with advanced agricultural and scientific knowledge who valued art and music as much a sound government and fair but brutal warfare.

On the other they were said to be magicians, necromancers, and in league with demons – no doubt embellished by the Christian monks who had to make sense of the earlier accounts of the TDD.

Whatever the case, these powerful semi-divine beings would ultimately have the sovereignty of Ireland, and with it the right to rule at Tara, seized from them by mere men – men who were powerful and wise in their own right, but nonetheless mortal.

According to myth, the Sons of Mil, King of Spain, travelled across the seas to the land now known as Ireland with their mother, daughter of the Egyptian Pharaoh Nectonibus. She was an Egyptian Princess and her name was Scotia. It is this Scotia from whom it is said the Island, and these settlers, got their name, the Scotii.

With vengeance on their minds they sought to slay the murderers of their kinsman, Ith, who had been killed by the TDD while on a previous excursion to the bountiful island. Fearing he would return with more people, the last three kings of the TDD, Mac Cuill, Mac Cécht, and Mac Gréine had jealously decided to kill Ith. Some members of his company managed to escape and raised the alarm with Ith’s kinsmen overseas who returned with boatloads of men and their families.

They were led by the great Druid-Poet-Judge Amergín. Having come to battle terms with the current rulers the Milesians sailed out to sea to a distance of nine-waves and, despite the TDD’s attempts to subdue the Milesians with their magical druidic storms, the Milesians made it to the island’s shores and succeeded in taking her as their own. It is said that from this point on all Kings at Tara were to be descended from the Sons of Mil.

Two of these sons, Eber and Eremon, were given sovereignty over half of the island each. To Eber was given the South and to Eremon was given the North. The ancient legends tell us that once all the peoples had been divided among the brothers equally there remained a single harpist and a single poet. Drawing lots between the two, Eber received the harpist and to Eremon the poet, and this is explained as the reason why the North has been famed for music and the South for poetry ever since. But it was a dispute over the Sacred Hill that ultimately led to a devastating rift that caused centuries of rivalry and unrest between the factions. It also gives us the account of where Tara or Teamhair got its name.

How the Hill of Tara came to be called Cnóc Teamhair

It begins when Eber’s wife requests that he procure the three most beautiful hills in Ireland for her possession; of which Tara was one. Eber desperately wanted to please his wife. The problem was the Hill of Tara was in Eremon’s northern half of the Island.

This audacious request and sheer greediness enraged Eremon’s wife Tea, daughter of a king of Spain, who in turn spurred her husband to battle.

During this battle Tea was killed and her body was buried on the hill now known as Tara, Teamhair or Tea Mur meaning: the Burial Place of Tea.

Eber was finally defeated by Eremon who assumed sole kingship of the island and is said to be the first of the Irish High Kings.

Many Irish Kings would come to be associated with the Hill of Tara appearing so frequently in our ancient accounts – it would be difficult to cover all of them in a short piece, but aside from the stories mentioned above there are a few other key legends worth mentioning to give an overall idea of the pre-eminence of this royal site.

Lugh Arrives at Tara

Lugh was one of the chief male deities of the ancient Irish. He is depicted a great warrior-god, a master of all the arts who would lead the Túatha Dé Danann to victory against the Fomorians – slaying their leader the mighty Balor of the Evil-eye with a slingshot; not unlike King David’s triumph over Goliath in the Bible. Linked to the sun and sun worship he is also compared to the Greek god Apollo. Such esteemed was he that he lends his name to one of the most sunny and bountiful months of an Irish year – Lughnasa, the month of August.

Lugh is being mentioned here in relation to the Hill of Tara to further illustrate the prestige and high esteem of the ancient site. His arrival at the royal site gives us an idea of the centre of excellence it once was. Taken from the story The Coming of Lugh, transcribed from Lady Gregory’s Complete Irish Mythology:

Now as to Nuada of the Silver Hand, he was holding a great feast at Teamhair one time, after he was back in the kingship.

And there were two door keepers at Teamhair, Gamal, son of Figal, and Camel, son of Riagall. And a young man came to the door where one of them was, and bade him bring him in to the king.

“Who are you yourself?” said the door-keeper.

“I am Lugh, son of Cian of the Túatha de Danann, and of Eithlinn, daughter of Balor, King of the Fomor,” he said; “and I am foster-son of Taillte, daughter of the King of the Great Plain, and of Echaid the Rough, son of Duach.”

“What are you skilled in?” said the door-keeper; “for no-one without an art comes into Teamhair.”

“Question me,” said Lugh; “I am a carpenter.”

“We do not want you; we have a carpenter ourselves, Luchtar, son of Luachaid.”

“Then I am a smith.”

“We have a smith ourselves, Colum Cuaillemech of the Three New Ways.” “Then I am a champion.”

“That is no use to us; we have a champion before, Ogma, brother to the king.”

“Question me again,” he said; “I am a harper.”

“That is no use to us; we have a harper ourselves, Abhean, son of Bicelmos, that the Men of Three Gods brought from the hills.”

“I am a poet,” he said then, “and a teller of tales.”

“That is no use to us; we have a teller of tales ourselves, Erc, son of Ethaman.”

“And I am a magician.”

“That is no use to us; we have plenty of magicians and people of power.”

“I am a physician” he said.

“That is no use; we have Diancecht for our physician.”

“Let me be a cup-bearer,” he said.

“We do not want you; we have nine cup-bearers ourselves.”

“I am a good worker in brass.”

“We have a worker in brass ourselves, that is Credne Cerd.”

Then Lugh said: “Go and ask the king if he has any one man that can do all these things, and if he has, I will not ask to come into Teamhair.”

The door-keeper went into the king’s house then and told him all that.

“There is a young man at the door,” he said, “and his name should be the Ildánach, the Master of all Arts, for all the things the people of your house can do, he himself is able to do every one of them.”

“Try him with the chess-boards,” said Nuada.

So the chess-boards were brought out, and every game that was played, Lugh won it.

And when Nuada was told that, he said:

“Let him in, for the like of him never came into Teamhair before.”

We can gather a lot from this mythical account. For one, it shows us there was a high regard and respect held for particular skills, and that such knowledge was a prerequisite for entering Tara. Lugh lists the skills of carpentry, metal work, battle, music, poetry and social etiquette. To put him to one final test, the wise king Nuada suggests he prove his worth through a game of great skill and strategy similar to our modern game of chess. Lugh wins and he is hailed the Samildánach – Master of all Arts.

Only then does he gain access to Teamhair.

King Cormac Mac Art

Cormac Mac Art was one of Teamhair’s greatest kings. A mighty warrior and a just lawgiver his legacy at Tara lives on today as one of the remaining earthen mounds is signposted as being his home.

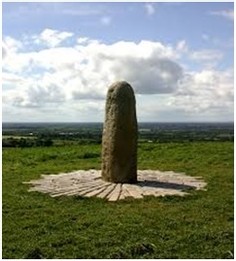

An Lia Fáil – The Stone of Destiny

Teamhair was also the home of the legendary Stone of Destiny. Also known as the Singing Stone, it was said that this magical artefact would let out a shriek when the rightful king touched it.

There is so much speculation and mystery around this Lia Fáil that it would require a separate post to go into more definitely.

Some say the Lia Fáil is the Stone of Jacob from the Bible, also the Stone of Scone, apparently situated under the Coronation Chair of English Monarchs.

What the earliest Irish myths tell us, however, is that this Stone was among four magical artefacts taken to Ireland by the Túatha Dé Danann that was said to shriek out or sing whenever the rightful king stepped foot upon it. The other artefacts included a magical spear, a sword, and a cauldron – all of which feature throughout the mythological cycles.

It is highly unlikely that the current phallus shaped stone atop Cnóc Teamhair is the same mythical stone of antiquity. Some accounts suggest the original was loaned by an Irish king to his brother, a king of the Scotii living in the land over the northern sea, in what we now know as Scotland. It is said that he borrowed the coronation stone with his brother’s permission so that he could be inaugurated according to his traditional customs. But the stone never returned to Ireland.

It was later seized by the English forces for use in the coronations of their own monarchs. There is an interesting modern chapter to this strange story. It has been suggested that during the 1940’s a group of Scottish Nationalist broke into Westminster Abbey, successfully stole the original stone and replaced it with a replica that remains to this day. There is a lot of information out there about this and Disney even used the plot in its film The Stone of Destiny.

The Lia Fáil is one feature of Teamhair that remains quite mysterious and truly rooted in the ancient mythical past. So far back it is difficult for us to understand now with modern eyes.

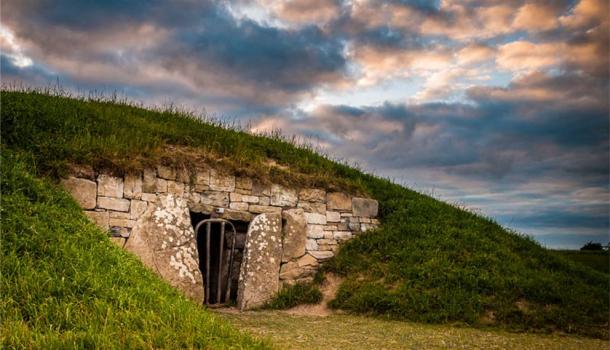

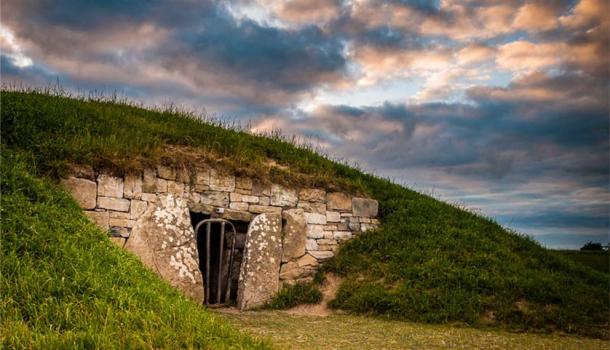

The Mound of Hostages: Duma na nGiall

One of the most striking mounds is also believed to be the oldest. Duma na nGiall, the Mound of Hostages, is said to be over 5000 years old (built c.3000 BCE).

While most of the Hill’s sites are Neolithic, the Mound of Hostages is the only one classed as Megalithic after excavations in the 1950’s discovered it to be much older than previously thought.

Human remains were found over successive excavations and the inside walls are carved with the sort of puzzling spiral carvings typical with ancient Irish sites.

What’s perhaps more interesting, and less well known, is that Duma na nGiall is also astrologically aligned; just like Newgrange in the closely situated Boyne Valley. However, where Newgrange is aligned to the Winter Solstice, the inner chamber of the Mound of Hostages is aligned to the rising suns on the special holidays of Imbolc and Samháin (February 2nd and November 1st), and the full moon of Lúghnasa (August).

Its current name is associated to the legendary Irish High-King, Níall Noígíallach, Niall of the Nine Hostages, who lived during the 4th Century and is generally accepted to be a real historical figure. He certainly seems to have left a lasting legacy. Recently, a team of Geneticists at Trinity College Dublin announced that up to 3 million men descend genetically from this ancient Irish king.

While currently associated with this 4th C. King the much earlier age of the Mound suggests it clearly had earlier names and uses:

The Mound of the Hostages (Duma na nGiall) owes its name to 19th century scholars who sought to identify visible monuments with places mentioned in 11th century manuscripts, associated with shadowy historical characters and events.

In fact, as the excavations reported here revealed, the Mound of the Hostages proved to be several millennia older than this, and is indeed the earliest of the major monuments on the Hill of Tara. (Source: Knowth.com)

Samháin: The Origins of Halloween

Celebrated today as a night of mischief and merriment, Hallowe’en has become a festival with its own modern traditions – but if you trace its roots all the way back you will find yourself on the Hill of Tara.

Originally known as Samháin (pr. SOW-an) in Gaelic, this harvest festival celebrated the closing of the yearly cycle marking a mile-stone where one should start to prepare for the coming darkness of winter. Officially falling on November 1st, it was traditionally celebrated for three days prior and three days after that date.

“At Samháin the leaders of the provinces of Ireland would congregate at Tara, where, amid religious rituals and much feasting, diplomatic missions were carried out and political alliances cemented. All the fires of Ireland were extinguished and then relit to symbolize the end of the old year and the beginning of the new.”

– Heroes of the Dawn, Time Life Books, p.37

Interestingly, Samháin remains the Gaelic word for November to this day. It was believed to be a special day – supernaturally – where the barrier between the seen and unseen worlds was at its weakest. A night when the spirits crossed over into our earthly plain.

With the onset of Christianity in Ireland – a campaign that was so successful because of its willingness to incorporate and co-opt local customs and beliefs; provided they didn’t contradict the doctrines of the Bible – the old Gaelic holiday became known as ‘All Saints Day’ or ‘All Hallows Day’ from which we get ‘All Hallows Eve’ or ‘Hallowe’en’, celebrated on October 31st.

Irish Mythology tells us how, having been beaten in battle, the People of Nemed (Nemedians) were forced to pay a brutal tax to the mysterious Formorii (Formorians) each year at Samháin. A time of celebration became a time of dread for the Nemedians who were annually deprived of 1/3rd of their crops, their cattle, and their children. This helps to explain some of our modern traditions.

With a very real and living belief in the ‘other-folk’, the people of earlier times genuinely feared being snatched away to the spirit world, at Samháin fears ran extra high. In an effort to trick the spirits and protect their children people would dress up in scary monstrous costumes. These spiritual beings were known as the sídhe (pr. shee – spirit/fairy) or daoine maithe (good-people) – a title aimed at appeasing the unseen ones, borne from the fear of their mystical wraths.

The Tragedy of Tara Today

Heritage sites, such as Tara, are still held in high regard and are much loved by the Irish people. Heavily protected in state legislative acts, the attitude in Ireland reflects a respect for the past and a longing to preserve it. Today, Tara is officially under the control of the Office of Public Works (OPW), a state-body charged with the care and management of public heritage sites. They act under the authority National Monuments Acts 1930, 1954.

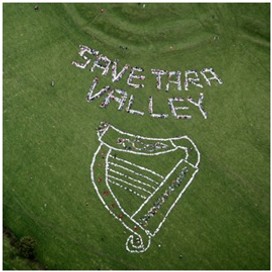

In spite of this, in the Irish Government approved plans for a new motorway to be constructed that would run about a mile from Tara Valley. Outraged at the disrespect for Ireland’s ancient heritage, many people protested and actively campaigned against the development.

“…opponents contend that a realistic definition of the hill must include the adjoining valley and nearby Hill of Skryne, all of which formed a coherent civilization from the Iron Age and are honeycombed with dozens of invaluable archaeological sites and a rich, if largely buried, history.”

(Source: Washington Post)

One mass demonstration involved over 1,500 people who gathered on the Hill in 2007 and positioned themselves into the shape of a giant harp with the words: ‘SAVE TARA VALLEY’ above.

Their cries went unheeded.

The M3 Motorway was opened on June 4th 2010, to the dismay of many.

Pingback: Builders, Kings, and Astronomers: 6 Ancient Sites to Explore the Ingenuity of Ireland's Ancestors - The Brehon Academy

Pingback: The Old Religion and the Druids: Lifting the Veil on the Mysterious Priests of Early Ireland - The Brehon Academy

Pingback: Raiders of the Lost Ark: British-Israelites and the Quest for the Ark of the Covenant on the Hill of Tara - The Brehon Academy