Delving into the depths of Irish history reveals a fascinating tapestry of mythology and legends. This intricate web of stories weaves together the tales of gods, goddesses, and a mysterious class of individuals known as the Druids. These ancient philosopher-scientists played a crucial role in shaping Irish culture and left behind a legacy that continues to captivate those who seek to unravel the mysteries of Ireland’s past. The Druidic beliefs and practices were deeply rooted in the reverence for nature and the spiritual practices that were inextricably linked to it. They were the keepers of oral tradition, and their influence extended to the seasonal festivals that are still celebrated in Ireland today. The Druids were mediators between different tribes and kingdoms, and their role in tribal mediation cannot be understated.

As we explore the captivating world of Irish myth and legend, we unravel the mystery of the Druids’ influence on ancient sites, High-Kings, and the collective narrative of the Irish people. Read on the learn more about the enduring influence and how the Druid’s impact can still be found throughout Ireland’s mythology and folklore, her music, literature, and art, and her ancient landscape. The preservation of cultural traditions and the importance of studying history and tradition are vital in understanding the enduring influence of Druidic beliefs on Irish culture.

Who Were the Druids?

The Druids were not a homogeneous group, and their practices varied depending on the region and time period. They were primarily located in areas of Gaul (modern-day France), Britain, and Ireland, and were active from around the 2nd century BCE until the Roman conquest in the 1st century CE. They were often associated with the Celtic tribes and were known for their skills in divination, healing, and prophecy. Seemingly, the druidic priesthood was open to both men and women alike.

Their in-depth knowledge of the world, nature, and human psychology made them prime advisors to the kings and chieftains of their respective societies, and their influence extended beyond religious and spiritual matters to include politics and social issues. As a result of their reverence for nature, often acting as environmental stewards in their communities, they have been described in modern times as the first green movement.

Despite their prominence in Celtic culture broadly speaking, little is known about the Druids because they did not leave behind any written records. Their teachings and practices were passed down orally, from one generation to the next, and were often kept secret.

The Romans and early Christian writers wrote about the Druids, but these accounts are often biased and may not accurately reflect their beliefs and practices. Nonetheless, the Druids remain an enduring and fascinating part of Celtic history and culture, and their legacy continues to inspire modern audiences.

These mysterious figures left an indelible impact on Irish history, despite the scarcity of information about their practices and beliefs. The Druids refrained from writing, believing that knowledge should be transmitted orally from master to pupil to prevent corruption. Consequently, our understanding of their lives and beliefs is primarily derived from Greek and Roman writers or Christian monks, who often portrayed them unfavorably.

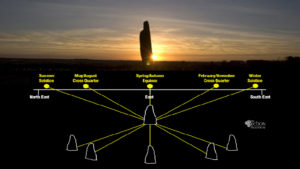

Still, the legacy of Druids and their profound intelligence is evident in their advanced mathematics and astronomical observations, which can still be found in the numerous standing stones and passage tombs aligned with the sun’s rising and setting during specific times of the year. These ancient sites, such as Newgrange and the Hill of Tara, highlight the importance of the sun’s movement and the seasons to the Druids, who personified this passage in the tales of their gods and goddesses. The Druids were revered for their knowledge and wisdom, and many Irish myths and legends feature Druids as prominent characters. The Druids were not only religious figures but also played a significant role in the arts, lawmaking, poetry, and storytelling.

Since so little is known about this mysterious class, this article will draw on evidence and resources from wider afield than Ireland. What that caveat in mind, the aim is to allow us to draw some generalisations in the hopes of getting us a little closer to understanding the druids of Ireland.

The Druids as Natural Philosophers: Nature, Astronomy, and the Infusion of the Sacred and the Mundane

The Druids were an ancient class of learned individuals in Celtic culture who served as spiritual leaders, teachers, and advisors. While much of their history and beliefs remain shrouded in mystery, they were known for their deep reverence for nature and their connection to the natural world. They believed that everything in the universe was interconnected and that all living things were infused with divine energy or spirit. As a result, they held natural sites, animals, and trees as sacred, and incorporated them into their religious practices.

The Druids as Spiritual Leaders: Their Role in Religious Practices

The Druids played a significant role in early Ireland as spiritual leaders, and their beliefs and practices centered around a deep reverence for nature and the natural world. The Druids served as intermediaries between the spiritual realm and the physical world, and their religious practices often involved the use of divination, prophecy, and healing. They believed that everything in the universe was infused with a divine energy or spirit, and they held natural sites, animals, and trees as sacred.

One of the most important sacred sites for the druids was the oak tree, which they believed was a symbol of strength, stability, and longevity. They often performed their rituals under or near oak trees, and considered them to be gateways to the Otherworld, a mystical realm that existed alongside the physical world. The yew tree was another important tree to the druids, as it was believed to have powerful medicinal and magical properties.

The Druids did not have a formal religious hierarchy or priesthood, and their religious practices were often conducted in outdoor settings such as sacred groves or standing stones. They held seasonal festivals to mark the changing of the seasons and to honor their gods and goddesses. Some of their most important deities included Cernunnos, the god of nature and fertility, and Brigid, the goddess of poetry, healing, and smithing.

The Druids in Society

The Druids’ role as spiritual leaders extended beyond the realm of religion to include politics and social issues. The Druids played a central role in the tapestry of Irish culture and history, as they combined the functions of judge, poet, and priest into a single office. They served as advisors to the kings and chieftains of their respective societies, and their advice was often sought on matters such as warfare, justice, and governance.

Religious and civil affairs were intertwined, with the Druids presiding over public ceremonies, from the inauguration of High Kings to the pronouncement of true judgments and the prediction of victory in battle. The Druids’ influence was such that they were able to mediate disputes between different tribes and kingdoms, and they played a key role in the formation and maintenance of alliances. These learned spiritual elders were revered, and their blessings and guidance were continuously sought.

The Work of the Druid: Storytellers, Judges, Musicians, Poets, and Historians

The Druids were not just religious figures but also artists and intellectuals who played an essential role in early Irish culture. They were likely the original law-keepers and historians, from whom the classes of the bards and seanchaithe (storytellers), breitheamhain (judges), and filidh (poet-historians) emerged. The bards were a distinct profession that emerged from the Druids’ legacy, and they had an equally important role in Irish society. They were known for their ability to praise and satirize individuals through their poetry and storytelling, which gave them immense power and influence. The bards also had the crucial responsibility of preserving Irish history and culture through their oral tradition (more below).

The Brehon, another profession derived from the Druids, were judges and legal experts who maintained the law and social order in ancient Ireland. They were respected for their knowledge of law and for their impartiality. The filidh, who were considered part of the bardic tradition, were poet-historians who recorded the history and genealogy of Irish families. They were revered for their ability to recall and recite extensive genealogies and histories, which were considered essential for maintaining social and political order.

Their advanced knowledge of mathematics provides a comfortable framework for mastering music and harmonics, which the druids are also often associated with. So it is not too much to suggest that the many orders of musicians, which were also integral to early Irish culture and society, also derived from the druidic class in an earlier time. Music played a significant role in social gatherings and ceremonies, and the musicians were respected for their talent and ability to entertain. It makes sense that the druid priests would be skilled in playing various instruments and singing songs that were often accompanied by dance, to either temper or assuage the tempers of the clan. Most notably the druids are associated with the harp, Ireland’s national emblem even today – under the Brehon laws, harp players were placed in the highest grade of the musical arts.

Druidical Teachers

Druids were masters of knowledge, seeking to unravel the truth about the world around them. They acted as the first philosopher-scientists, setting themselves apart from the masses by possessing the mental tools to understand nature, psychology, and the physical universe. Given their role as the earliest repositories of knowledge, and their remarkable influence on both the arts and the civil structures and social rituals of the day, the druids may also be credited for creating the first true schools on the island of Ireland.

Magical Weapons of War

However, their magic spells were feared, and they may have concocted love potions, as mentioned in law texts and other sources. Some of their sorcery was carried out through a process that may to ‘heron or crane-killing,’ or possibly ‘mocking’, that seemingly involved standing on one leg with one arm raised and one eye shut in imitation of a heron’s stance. For this reason, it was believed that the druids’ power could be useful in war. It is more likely that these phenomena were merely the common people’s way of interpreting the scientific and psychological processes the Druids were engaged in.

The Annals of Ulster recorded the use of a druidic fence in the battle of Cuil Dremne, which killed any warrior who leaped over it. According to Bretha Nemed legal texts, a druid could ensure victory for the weaker side in battle. Despite their apparent influence, the advance of Christianity and the associated reduction in the druid’s status led to their eventual decline, and by the time of the law texts, their position was that of a sorcerer or witch doctor. Nevertheless, the druid’s mysterious legacy has endured, and their traditions have been preserved and passed down through the ages.

Ancient Propagandists: The Druidical Power of Praise and Satire in Early Irish Society

Praise and satire were powerful tools in early Irish literature, feared by those in power. Satire was perceived as a demonic power and could physically harm those who were satirized. The effect of a poet’s satire was so great that it is still feared in Ireland to this day. In ancient Ireland, only noblemen were allowed to travel beyond the borders of their tuath without permission, such was the fear of satire.

The Bards and the more elite Fili (poet-historians) professions that emerged from the Druids’ legacy had a significant role in Irish society. The role of the fili, or poet, in early Irish society was complex and multifaceted. While they were known for composing praise poetry eulogizing the great accomplishments of their patrons or extolling the virtues of their ancestors, they were also notorious for their dreaded negative counterpart: satire.

The fili were often employed to satirize those who crossed their patrons, and people in Irish society were nervous about the power of the fili to determine their fate. A bard might write a poem or song about a person they liked, but if they didn’t like them, they could extort them for riches in return for not writing satire about them.

The Satire of Bres: A Tale From Irish Mythology

The following is a story from the Mythological Cycle of Irish mythology that tells of ‘the first satire in Ireland.’ It is issued by the poet Cairpre who was a poet of the Tuatha Dé Danann (TDD) after he had sought hospitality from Bres Mac Eladain, who was then the sovereign of Ireland. Bres was known for his beauty and was compared to every great and beautiful thing on earth. However, he was unpopular as a leader because he forced champions of the TDD into humiliating servitude, including two of the strongest of the Tuatha Dé Danann, Ogma Mac Eladain, and the Dagda (Ogma was forced to carry a load of firewood, while the Dagda was set to dig ditches and fortify Bres’s fortress).

Who was the first person to be satirized in Ireland?

It was Bres Mac Eladain.

And who was responsible for this satire?

The poet Cairpre Mac Edaine of the Tuatha Dé Danann.

What caused the satire?

The poet had come to seek hospitality from Bres, who was at the time the sovereign of Ireland.Cairpre Mac Edaine was given a small, dark, and narrow house with no fire, bath, or bed. He was given three dry cakes on a little dish. The next day, he was displeased, and as he crossed the court, he made the following proclamation:

“Without food speedily on a platter,

The Satire of Bres by Caripre Mac Edaine

Without a cow’s milk whereon a calf thrives,

Without a man’s habitation after the staying of darkness,

Be that the luck of Bres Mac Eladain”.

From that moment on, Bres’s riches did not continue, and he was shortly expelled from his kingship. Bres then gathered his paternal relatives, the Fomorians, and fought against the Tuatha Dé Danann, resulting in the Battle of Moytura. Bres himself fell in the conflict.

Druidism and Christianity in Early Ireland

Long before Christianity took root in Ireland, early humans sought to comprehend the natural forces that governed their world. These forces were personified and assigned names, which eventually evolved into real entities that people believed in. This Irish mythology, teeming with gods and goddesses, served as the living myth and collective story of ancient Irish culture. With the advent of Christianity, these once-mighty gods transformed into the fairy folk who inhabited the hills of Ireland.

The Druids in pre-Christian Ireland held a high social status, comparable to their British and Continental counterparts. The druid, known in Old Irish as ‘drui‘, held the roles of priest, prophet, astrologer, and teacher of the nobles’ sons. The First Synod of Saint Patrick in the 6th century stated that oaths were sworn in the presence of the druid. However, with the advent of Christianity, the druid’s position was reduced to that of a sorcerer or witch doctor. Despite being discriminated against in law, the druid remained influential enough to secure inclusion among the nemeds (noble classes) of the Uraicecht Becc, an Irish legal manuscript that deals with status, among other topics.

The Druids’ decline began with the arrival of Christianity in Ireland, which challenged the existing beliefs and practices of the Druids. The Christian missionaries believed that the Druids were pagan and evil, and they set out to convert the Irish people to Christianity.

Over time, the Christian church gained more power and influence in Ireland, and the Druids’ position in society diminished. By the time of the medieval Irish law texts, the Druids’ position was reduced to that of a sorcerer or witch doctor. However, the Druids’ legacy has endured, and their traditions have been preserved and passed down through the ages.

One example of this Druidic-Christian influence on Irish cultural identity can be found off the west coast on the Aran Islands. These islands were once a retreat for contemplative and learned individuals, and the natives have preserved many of the moral and physical remains of the ancient world. They believe that the remains of the Druids are inviolable and belong to aerial beings and that the circular mounds or cairns are the sepulchers of mighty men of renown, whose acts and deeds are celebrated in songs.

The Druids revered the sun, moon, and stars, with the sun considered the noblest type of Godhead. They used mysterious stones, sometimes called zodiacal rings, in their sacrifices, and cattle were subject to purifying ordeals until a late period. The Druids kindled two immense fires with incantations between which cattle were driven, and if they escaped unharmed, it was considered auspicious. The mysteries of Druidism were not written down, and their teachings were possibly in Greek. They were named after the oak tree, which they frequented, and used in their sacrifices. Sadly, the departure of Druidism resulted in the disappearance of the forests from Aran. It is important to preserve the remnants of these ancient civilizations and to restore the natural environment of the Aran Islands. We should hope for reforestation in the future, providing the islanders with timber to burn and preserving a unique aspect of Irish.

The beguiling Druids of Irish culture have left an indelible mark on the history, mythology, and legends that continue to define Ireland. As enigmatic philosopher-scientists who sought to understand the world around them, the Druids played a pivotal role in shaping ancient Irish society, leaving behind a legacy of fascinating stories and mysterious ancient sites that continue to enthrall those who delve into the captivating world of Irish myth and legend.

Sources and Additional Materials

- Cairpre mac Edaine’s Satire Upon Bres mac Eladain TCD 1336 (formerly MS H3.17)

- John Toland, History of the Druids (1814)

- The Lebor Feasa Runda – Druidic Grammar of Celtic Lore

- The Druid (Misc Essays) (1812)

- Rev. Canon J.F.M. French, Prehistoric faith and worship- glimpses of ancient Irish life (1912)

- E. Carpenter, Ancient pagan and modern Christian symbolism (1922)

- Rev. Richard Smiddy, An Essay on the Druids, The Ancient Church, and The Round Towers of Ireland (1871)

- Jacob des Moulins, A Concise Historical Account of the Ancient Druids (1794)

- O. J. Burke, “Druids” in The south isles of Aran (County Galway) (1887)

Pingback: Irish Tales of the Otherworld and Parallel Traditions - ConnollyCove